A recent post considered petitions for review in criminal cases filed during the 2014-15 term and concluded with the observation that a comparison of the results with findings from previous terms would provide some helpful perspective. Toward that end, I began by working through data for three different sets of terms: (1) 2012-13 through 2014-15 (referred to hereafter as the “recent terms”); (2) 2004-05 through 2006-07 (hereafter the “Butler terms”); and (3) 1996-97 through 1998-99 (hereafter the “late 1990s”).[1]

The “recent terms” were selected as the best indicator of the behavior of the current court, all of whose members, except for the newly-appointed Justice Rebecca Bradley, served together with the late Justice Crooks throughout the period.

The “Butler terms” cover three of the four terms during which Justice Butler served on the court, thereby providing the court with three liberal members. Given that the votes of at least three justices are required to grant a petition for review, it seemed reasonable to ask whether the presence of three liberals (Justices Abrahamson and Ann Walsh Bradley along with Justice Butler) would generate statistics at sharp variance from those for the “recent terms.”

The “late 1990s” were included to ascertain what difference, if any, would result from the absence of Justice Butler and also the court’s current conservative members (Justices Roggensack, Ziegler, and Gableman).[2]

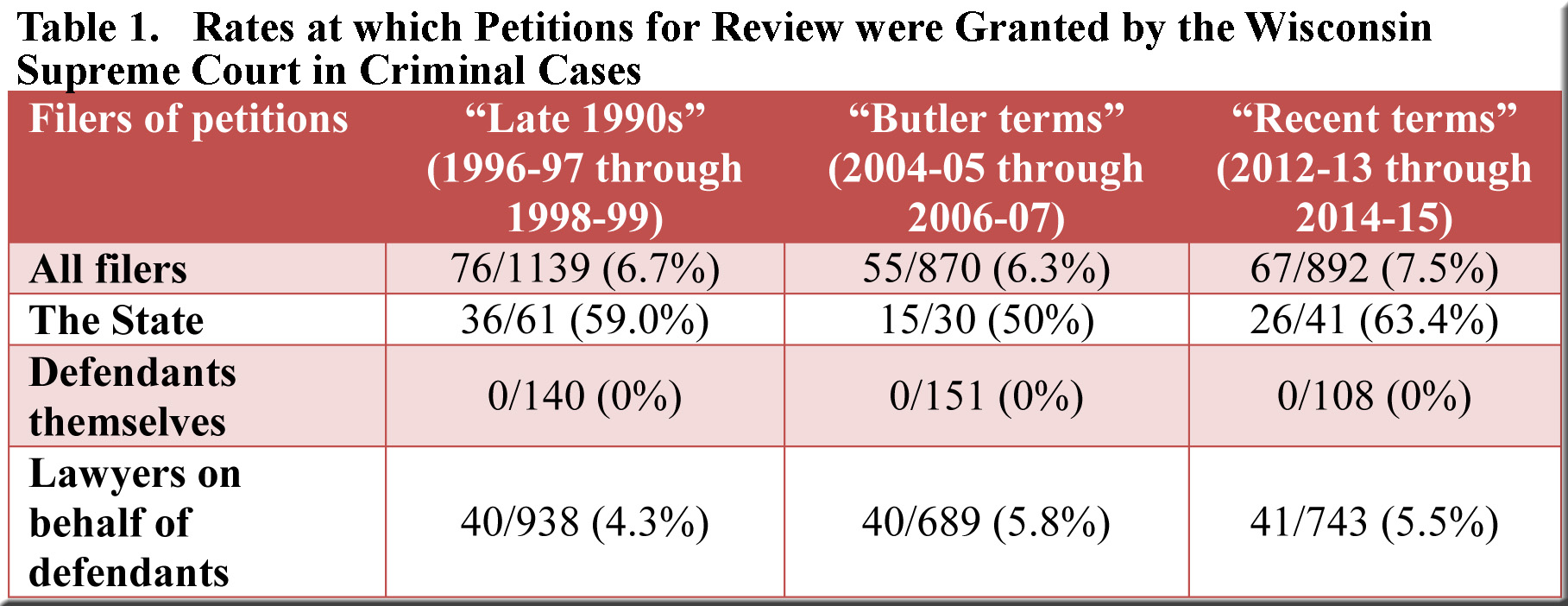

The results of the study displayed in Table 1 suggest that the “recent terms” fit within the normal range of decisions made by justices voting on petitions for review filed during the previous two decades.[3] During the “recent terms,” for instance, the justices granted petitions for review filed by the State at a rate that considerably exceeded the figure for the “Butler terms” (63% compared to 50%, respectively) but did not differ much from the figure for the “late 1990s” (59%). Moreover, lawyers who filed petitions on behalf of defendants found them granted only slightly more often during the “Butler terms” than during the “recent terms” (5.8% compared to 5.5%)—and they were granted less frequently (4.3%) during the “late 1990s” than during the “recent terms.” Defendants who filed petitions on their own, rather than through lawyers, found the court as inhospitable during the “Butler terms” as in either the preceding or subsequent periods.

(click on the tables to enlarge them)

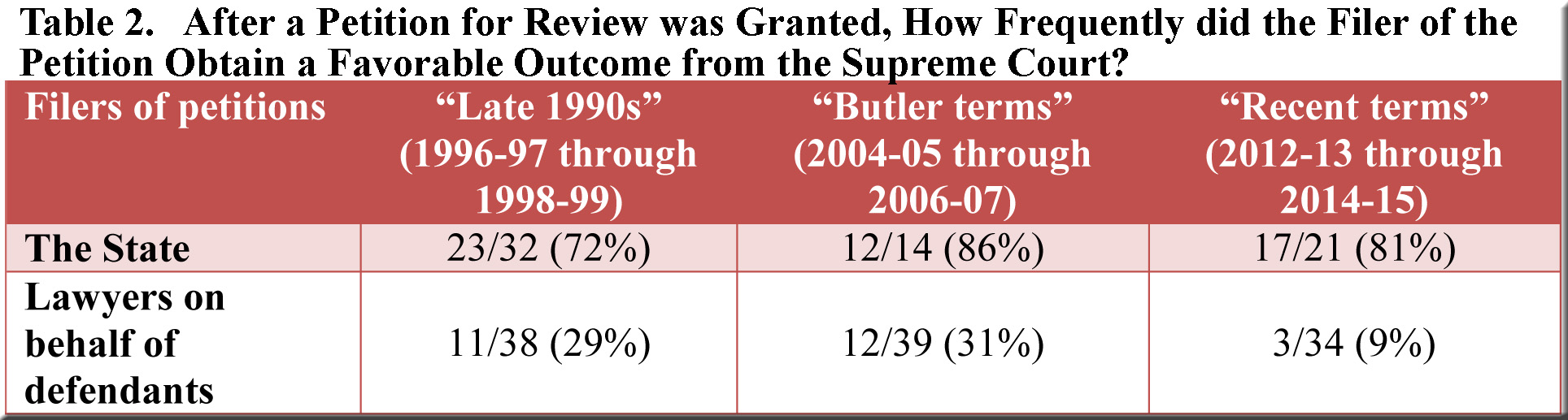

All in all, were we to stop at this point, a reader might well be impressed more by the continuity rather than the change when comparing the “recent terms” with the preceding periods. The question remains, though, what happened after a petition for review was granted? Although a “grant” was indispensable to a filer’s cause, it by no means signaled that a successful outcome was likely thereafter—certainly not for all categories of filers. And here, when we inquire about the outcomes obtained after petitions for review were granted, the “recent terms” depart significantly not only from the “Butler terms” but also from the “late 1990s.”

To be sure, this cannot be said of the State’s petitions for review. When these were granted, the court proceeded to rule in the State’s favor the large majority of the time in every term—slightly more often, in fact, during the “Butler terms” than during the “recent terms”—as shown in Table 2.[4]

But when the court granted petitions filed by lawyers on behalf of defendants, it then ruled against the defendants far more often during the “recent terms” than during the earlier periods. More specifically, only 9% of these successful petitions filed on behalf of defendants led to favorable outcomes for the defendants during the “recent terms,” compared to success rates of 31% and 29% during the two preceding periods. Thus, in recent years, defendants have had much less reason for optimism than in the past, upon learning that their petitions for review were granted.[5]

[1] Once again, I am grateful to Diane Fremgen, Clerk of the Supreme Court and Court of Appeals, who furnished data on petitions for review. Cases under consideration are those bearing the CR suffix (the same category described in more detail in the footnote accompanying the initial post). In addition, I should note that when a party filed two petitions for review during the lifespan of a single case (an unusual occurrence), I counted both petitions—as I did when both parties petitioned for review in the same case. I did not count a petition on the rare occasion when the justices “took no action” on it.

[2] Composition of the Wisconsin Supreme Court:

2008-09 through 2014-15

(Justices Abrahamson, Bradley, Crooks, Prosser, Roggensack, Ziegler, and Gableman)

2007-08

(Justices Abrahamson, Bradley, Crooks, Prosser, Roggensack, Ziegler, and Butler)

2004-05 through 2006-07

(Justices Abrahamson, Bradley, Crooks, Prosser, Roggensack, Butler, and Wilcox)

2003-04

(Justices Abrahamson, Bradley, Crooks, Prosser, Roggensack, Wilcox, and Sykes)

1999-00 through 2002-03

(Justices Abrahamson, Bradley, Crooks, Prosser, Wilcox, Sykes, and Bablitch)

1998-99

(Justices Abrahamson, Bradley, Crooks, Prosser, Wilcox, Bablitch, and Steinmetz)

1996-97 through 1997-98

(Justices Abrahamson, Bradley, Crooks, Wilcox, Bablitch, Steinmetz, and Geske)

[3] Click here for an expanded version of Table 1 that provides figures for each of the nine terms individually.

[4] Click here for an expanded version of Table 2 that provides figures for each of the nine terms individually.

[5] Occasionally it was impossible to categorize an outcome as favorable or unfavorable for a successful filer of a petition for review. In these instances, I omitted the case from Table 2. Figures for 2014-15 are incomplete in Table 2, because the court has yet to file decisions in a majority of the criminal cases (included in Table 1) for which the justices granted review.