A post at the end of the 2019-20 term noted the soaring number of original-action petitions accepted by the court and suggested that this could be regarded as a measure of judicial activism. Today we’ll revisit the topic to see how data for 2020-21 compare to that of previous terms—and explore the possible impact on these figures produced by changes in the court’s membership.

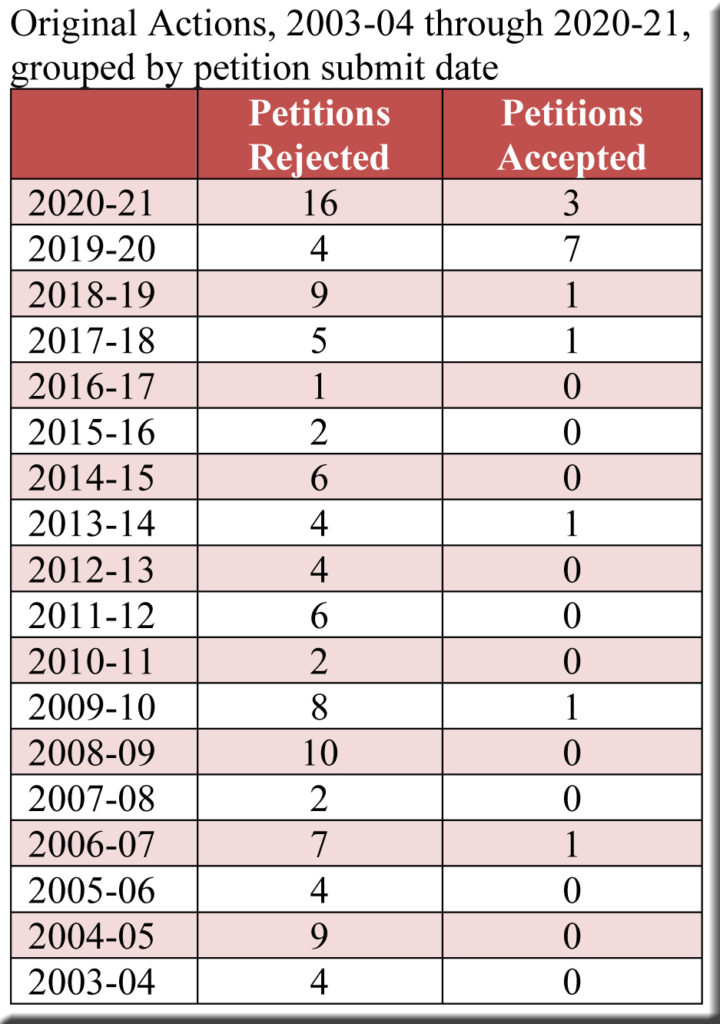

Two things are clear in the following table.[1] First, far more original-action petitions were submitted in 2020-21 than in any of the previous 17 terms, and second, the number of these petitions accepted by the justices was less than half the number of petitions accepted in 2019-20 (though more than in any of the preceding terms).

This seems straightforward, as does the fact that the three accepted petitions were all filed by conservative entities, reflecting the court’s prevailing orientation. However, beneath these basic figures much of interest awaits us, especially if we poke around among last year’s unprecedented number of rejected petitions.

Disregarding the four petitions submitted by prisoners or other pro se litigants in 2020-21 (denied by the court, and virtually assured of rebuff in any year), we are left with 12 rejected petitions. Nearly all were filed on behalf of conservative causes—challenging election procedures or various COVID-19 responses—and fully eight of these 12 “politicized” rulings included separate opinions revealing the stances taken by individual justices.[2] These concurrences and dissents reward scrutiny, for they indicate just how close the court came to accepting a much larger number of original actions.

The decisive role of Justice Hagedorn—once again

All eight of the petitions were rejected by a 4-3 vote—with Justice Hagedorn the only member of the court in the majority in every instance. More bluntly, the petitioners had no way forward without him. Just as striking, in seven of the eight cases, Justice Hagedorn joined the three liberals (Justices AW Bradley, Dallet, and Karofsky) to deny petitions favored by all three of the court’s most conservative justices (Roggensack, Ziegler, and RG Bradley).[3]

In Gymfinity, LTD. v. Dane County (regarding Dane County’s effort to combat COVID-19 by banning indoor gatherings), he proceeded cautiously. After noting his support for original-action petitions in certain COVID-related cases, he explained that in Gymfinity several claims involved factual issues better suited for a circuit court. However, he was less restrained in some of the other cases, including Wisconsin Voters Alliance v. WI Elections Commission, where a group of Republican voters asserted that Donald Trump would have won Wisconsin in the absence of thousands of ballots which they challenged. Although Justices Roggensack, Ziegler, and RG Bradley desired to accept this petition, Justice Hagedorn did not:

But the real stunner here is the sought-after remedy. We are invited to invalidate the entire presidential election in Wisconsin by declaring it “null”—yes, the whole thing. And there’s more. We should, we are told, enjoin the Wisconsin Elections Commission from certifying the election so that Wisconsin’s presidential electors can be chosen by the legislature instead, and then compel the Governor to certify those electors. At least no one can accuse the petitioners of timidity.

The previous day, when the court rejected an original-action petition in Donald J. Trump v. Anthony S. Evers (challenging election proceedings in Dane County and Milwaukee County), Justice RG Bradley’s dissent (joined by Justices Roggensack and Ziegler) voiced support for the petition: “The majority’s failure to act leaves an indelible stain on our most recent election. It will also profoundly and perhaps irreparably impact all local, statewide, and national elections going forward, with grave consequence to the State of Wisconsin and significant harm to the rule of law.” Justice Hagedorn thought otherwise: “Following this law [spelling out the procedure for challenging election outcomes] is not disregarding our duty, as some of my colleagues suggest. It is following the law. … We do well as a judicial body to abide by time-tested judicial norms, even—and maybe especially—in high-profile cases. Following the law governing challenges to election results is no threat to the rule of law.”

What a difference an election can make.

Were it not for the defeat of Justice Kelly by Justice Karofsky in April 2020, it seems certain that a considerably larger number of original-action petitions would have been accepted in 2020-21. As we have seen, all three of court’s most stalwart conservatives stated their desire to grant seven additional petitions in 2020-21, and one can readily imagine Justice Kelly siding with them in all, or nearly all, of these cases. Indeed, Justice Kelly’s presence in 2019-20 goes some distance in accounting for the exceptional number of original actions accepted that term, for his vote shielded Justices Roggensack, Ziegler, and RG Bradley from concern over Justice Hagedorn’s qualms. Had Justice Kelly been onboard in 2020-21, the immediate aftermath of Wisconsin’s 2020 election could easily have been quite different—resembling, perhaps, the current endeavors of former Supreme Court Justice Michael Gableman.

[1] Terms run from September 1 through August 31 of the following year. The petitions are classified in one term or another according to the “submit date” in CCAP—and not, for instance, according to the date on which the court issued a final ruling (though, usually, either date would place a petition in the same term). This is a slightly different (and clearer) method of categorization than that adopted in the original post, though the primary impression—a much larger number of petitions accepted in 2019-20 than in previous years—is unchanged.

[2] It may be that liberal organizations saw little point in filing original-action petitions, given the court’s current membership.

[3] Only in Lori O’Bright v. Kami Lynch did the rejected petition find favor from the court’s three liberals. Here, the issue centered on 13,500 absentee ballots in two counties that had been mailed with a minor printing error. Local officials declared their uncertainty over how to handle the problem, because the law required that such ballots be processed in a manner all but impossible to complete by the statutorily-imposed deadline. They sought the court’s guidance on proper procedure, which the court’s majority declined to provide. In the words of Justice Roggensack’s concurrence, the clerks for Outagamie County and Calumet County “ask us to assume original jurisdiction and issue what amounts to an advisory opinion explaining what election laws they are free to disregard. We will not do that.”

[…] term, under a conservative majority, the court accepted three original actions, according to a tally from Marquette University Professor Alan Ball, a diligent court tracker. During the 2019-20 term, […]