With the term’s last three substantive decisions now in the books, the door has opened for our annual series of posts inspecting the justices’ labors. The term did not lack unusual and dramatic features, one of which serves as our focus today.

Number of decisions filed

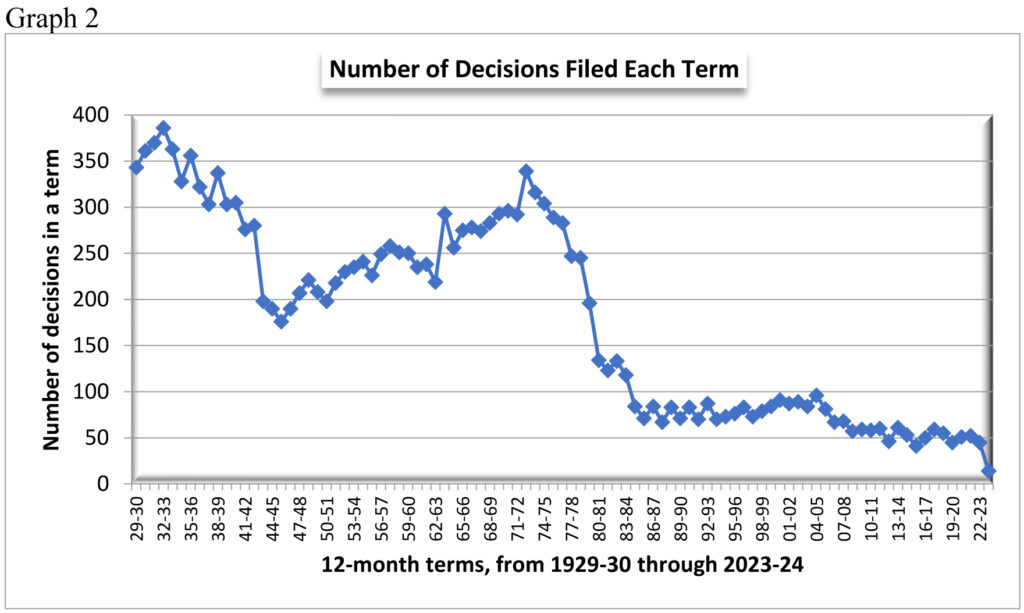

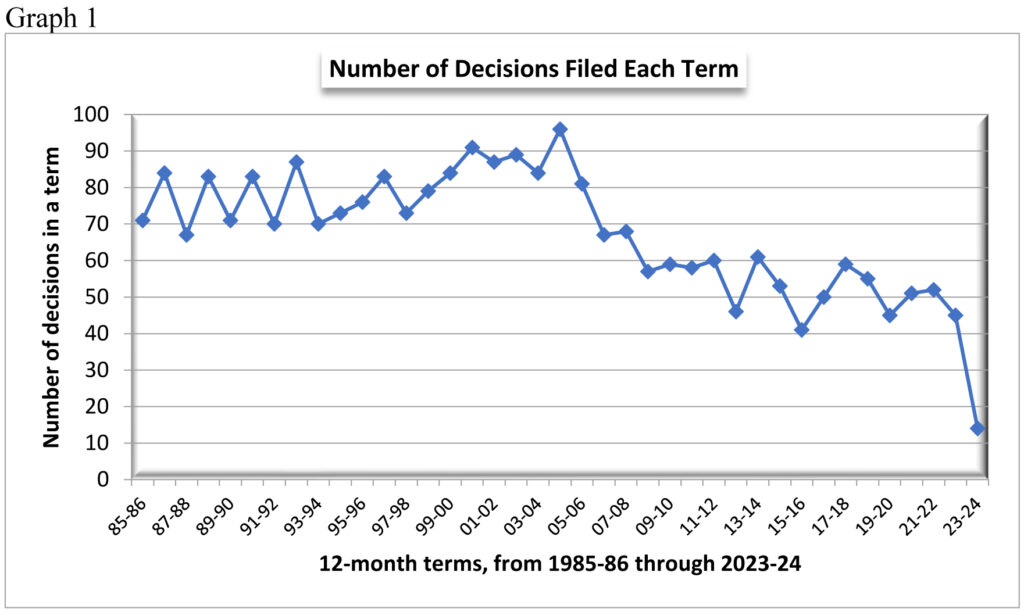

Nothing about this term’s batch of decisions is more eye-catching than its diminutive size. Last year’s post described the court’s output of 45 decisions as “strikingly low,” but it now seems like a torrent compared to this year’s total of 14.[1] Not only is this an extraordinary plunge in relative terms (a 69% drop), the sum of 14 decisions is a miniscule portion of the yield for any other term in the past century (Graphs 1 and 2).

Why has this happened? It’s clearly not sufficient to observe that many appellate courts around the country have been filing fewer decisions during the 21st century. Although this is true of the Wisconsin Supreme Court, as displayed in Graph 1, the decline from 45 decisions to 14 this term is unprecedently sharp. Even when the new Wisconsin Court of Appeals (created at the end of the 1970s) began handling many cases that would formerly have reached the supreme court, the justices’ output dropped far less in percentage terms than it did in 2023-24.[2] In other words, what we have witnessed this year is more than just a predictable step in a long-term trend—and thus we return to the question with which this paragraph began. What could account for such a precipitous change? A recent article discussed certain factors that may have contributed, and today we’ll examine another.

Why has this happened? It’s clearly not sufficient to observe that many appellate courts around the country have been filing fewer decisions during the 21st century. Although this is true of the Wisconsin Supreme Court, as displayed in Graph 1, the decline from 45 decisions to 14 this term is unprecedently sharp. Even when the new Wisconsin Court of Appeals (created at the end of the 1970s) began handling many cases that would formerly have reached the supreme court, the justices’ output dropped far less in percentage terms than it did in 2023-24.[2] In other words, what we have witnessed this year is more than just a predictable step in a long-term trend—and thus we return to the question with which this paragraph began. What could account for such a precipitous change? A recent article discussed certain factors that may have contributed, and today we’ll examine another.

Longer decisions?

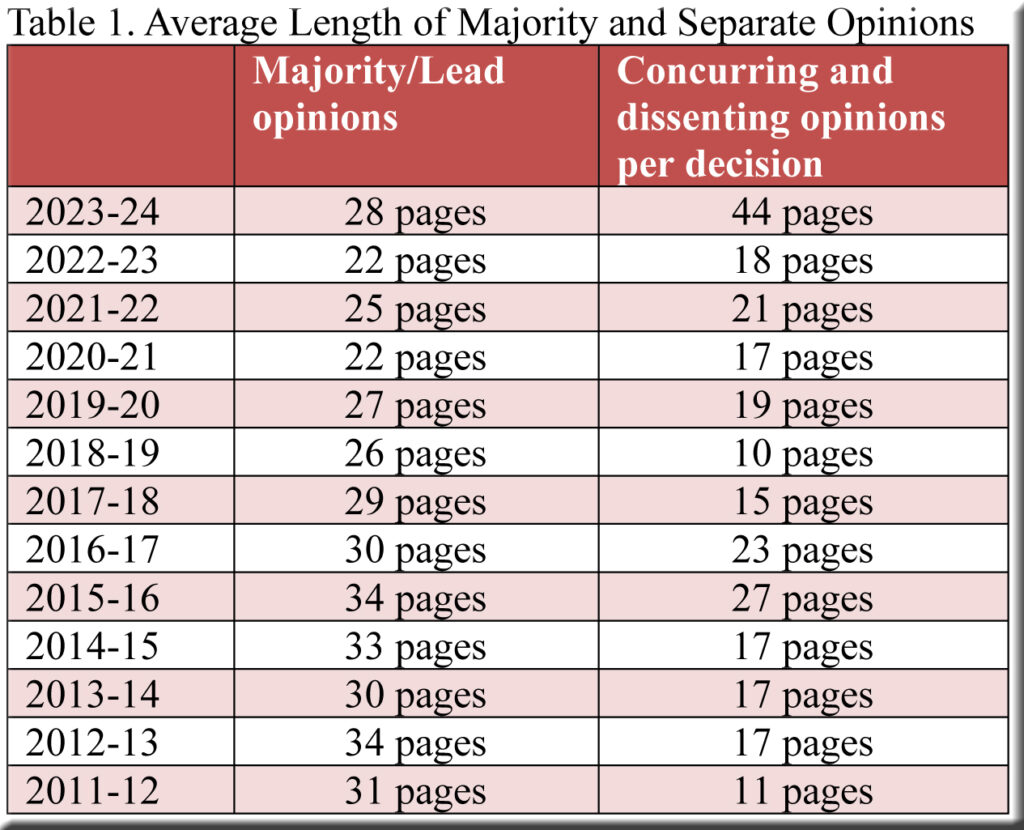

The average length of decisions filed in 2023-24 was much larger than ever before (Graph 3),[3] and this probably goes some distance toward explaining their smaller number.

It’s worth noting that most of the decisions’ added bulk was supplied not by majority opinions (which remained at the average for the years covered in Table 1), but by concurrences and dissents. They averaged a total of 44 pages for each decision, eclipsing the figure for every other year in the table.[4]

Caution

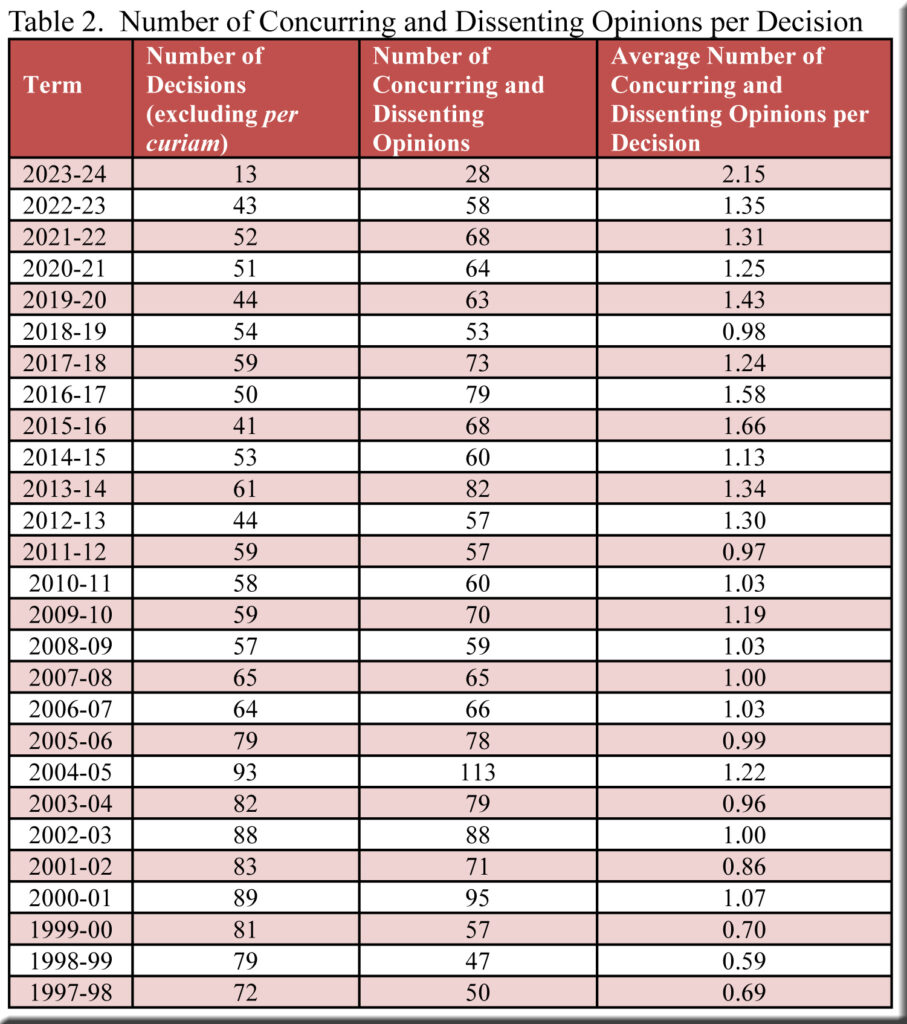

Although the lengthy separate opinions characteristic of 2023-24 may have reduced the total number of decisions for the term, this conclusion should be tempered. First of all, while the justices did file more separate opinions per decision in 2023-24 than previously, the total number of separate opinions in 2023-24 was less than half the totals for recent years, as shown in Table 2. In fact, the total number of pages devoted to separate opinions in 2023-24 (575 pages) shrank before the totals for 2022-23 (772 pages), 2021-22 (1105 pages), and 2020-21 (850 pages)—years when the court’s output dwarfed that of 2023-24.

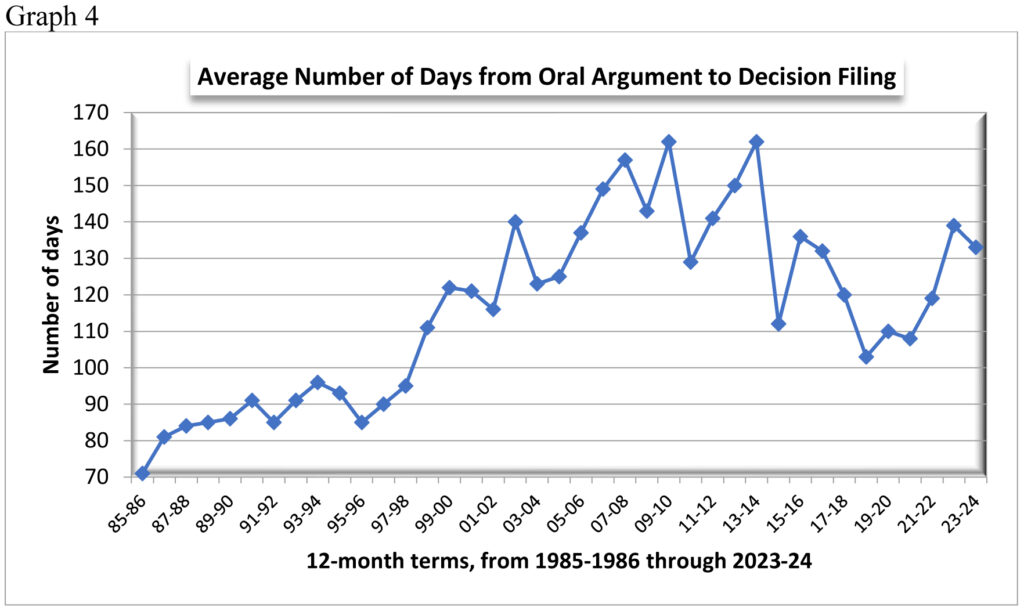

Also, if the writing and circulating of numerous substantial concurrences and dissents bogged down the justices and thereby contributed to the tiny number of decisions this term, one might guess that the average number of days between oral argument the filing of a decision would exceed the norm for preceding terms. Such was not the case, however, as demonstrated by Graph 4, where we find the figure for 2023-24 (133 days) well within the range for the past 20 years. Perhaps the unusual length of decisions this term was balanced by their unusual scarcity, producing the “routine” result in Graph 4.

Conclusion

As we’ve seen today and in the article noted above, the court’s meager yield this term could have stemmed from a variety of factors—each plausible but each with limitations that hinder identification of the principal cause of such a significant development. Maybe there was no principal cause. If readers can suggest other considerations that might have played a part, I would be grateful.

Meanwhile, the volume of decisions was not the only remarkable change during the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s 2023-24 term, leaving us much to explore in upcoming posts.

[1] The total of 14 decisions does not include two deadlocked (3-3) per curiam decisions (State v. Donte Quintell McBride and State v. Morris V. Seaton) and two cases dismissed as improvidently granted (Amazon Logistics, Inc. v. LIRC and Winnebago County v. D.E.W.).

[2] Compare, for instance, the percentage decline in the number of decisions in 2023-24 (69%) with that for 1979-80 (20%) and 1980-81 (32%).

[3] The figures plotted in the graph are for full decisions—majority opinions plus separate opinions. They include the title pages but not the blank page at the end of each decision. Per curiam decisions are omitted, as are appendices (which are very rare).

[4] The figures for majority/lead opinions do not include title pages (that is, the pages at the beginning of a decision that list the case title, the parties, and the attorneys). To be clear, the figures for separate opinions are not the average length of a single concurrence or dissent. They are the average number of pages per decision of concurrences and dissents combined. They do not include per curiam decisions.

A later post will indicate how many concurrences and dissents were written by each justice.

I think there’s another reason that would tend to show that the length of decisions has nearly nothing to do with the number of decisions released. The decision to take a case is made, roughly speaking, about 8-10 months before the case is actually decided (take your average days from oral argument until release above, add 60 days for briefing and 1-3 months between the completion of briefing and oral argument). So the approximate number of cases that would be decided this term was established long before anybody knew how long the opinions would be.

Contributing to this conclusion is the fact that, unlike the Court of Appeals, SCOWIS operates on a strict term and must finish all its opinions by June 30 (administrative preparation between the justices’ finishing and the actual release) accounts for why they bleed into July). If the Court of Appeals takes longer because opinions are longer, that just pushes other opinions further down the road. Not so with SCOWIS.

It’s true that the anticipation of lengthier opinions might incentivize justices to take fewer cases. But that effect you would expect to be gradual – as cases get longer over the years, you would expect to see fewer. Which we do in fact see, so that might explain the steady decline. But it doesn’t explain this term’s precipitous drop.