Two terms have passed since our last Fourth-Amendment update, and significant developments have transpired in the interim. For one thing, Justices Rebecca Bradley and Daniel Kelly have now been on the court long enough (four terms and three terms, respectively) to yield a substantial quantity of votes on Fourth-Amendment cases. We have also gotten our first glimpse of Justice Rebecca Dallet’s stance, though only general and preliminary conclusions are possible so early in her tenure. Other topics beckon as well, and we’ll begin with an overview of the number of Fourth-Amendment cases decided each term.

Number of Fourth-Amendment Cases

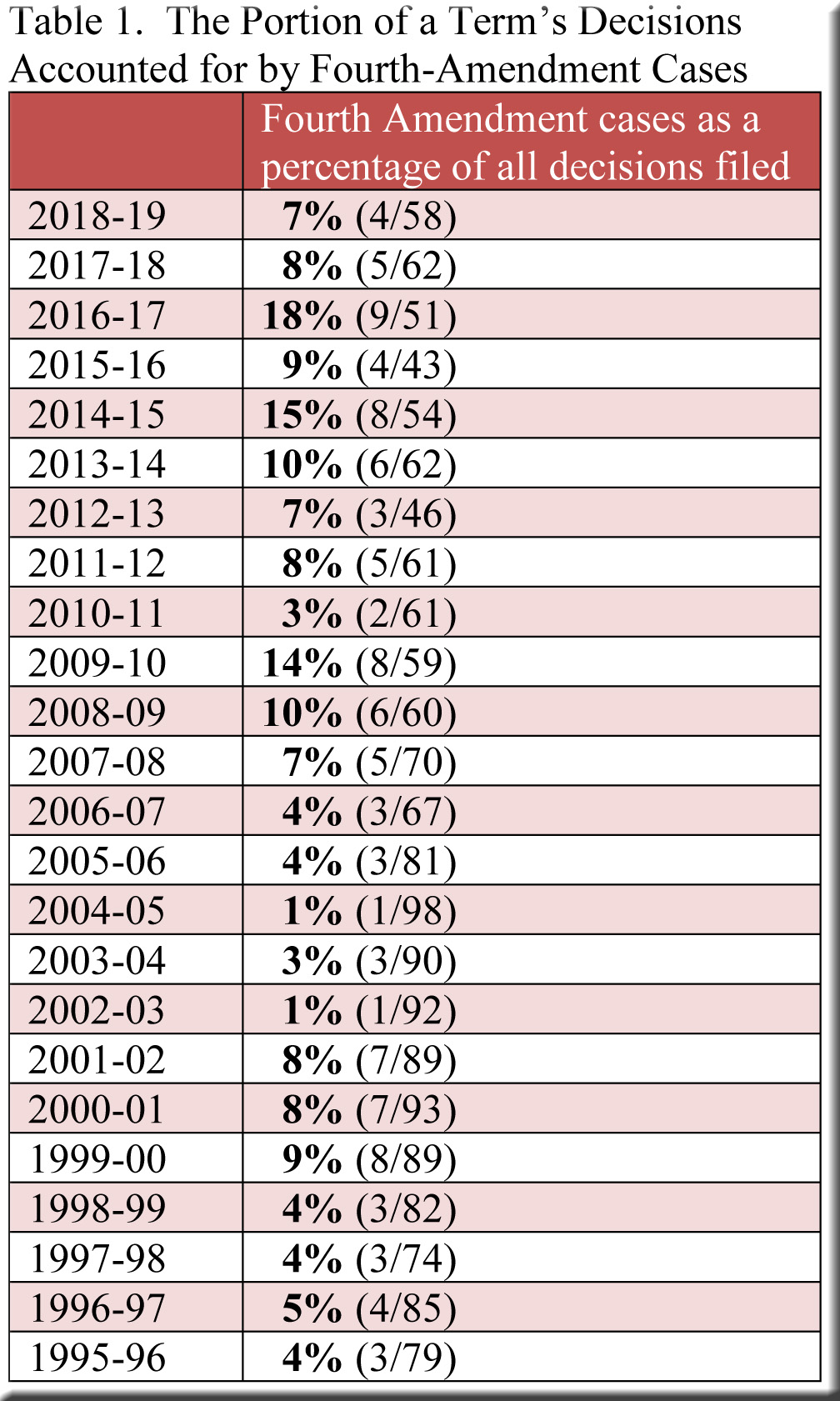

The previous post noted that the court devoted a larger percentage of its docket to Fourth-Amendment cases in 2016-17 than at any other point in the 22 terms then covered by the study. Indeed, the six highest percentages all came between 2008-09 and 2016-17, which, at the time, suggested a definite trend. However, the figures for 2017-18 (8%) and 2018-19 (7%) in Table 1 indicate a return to numbers closer to the average for the entire period.

Percentage Favorable to Defendants

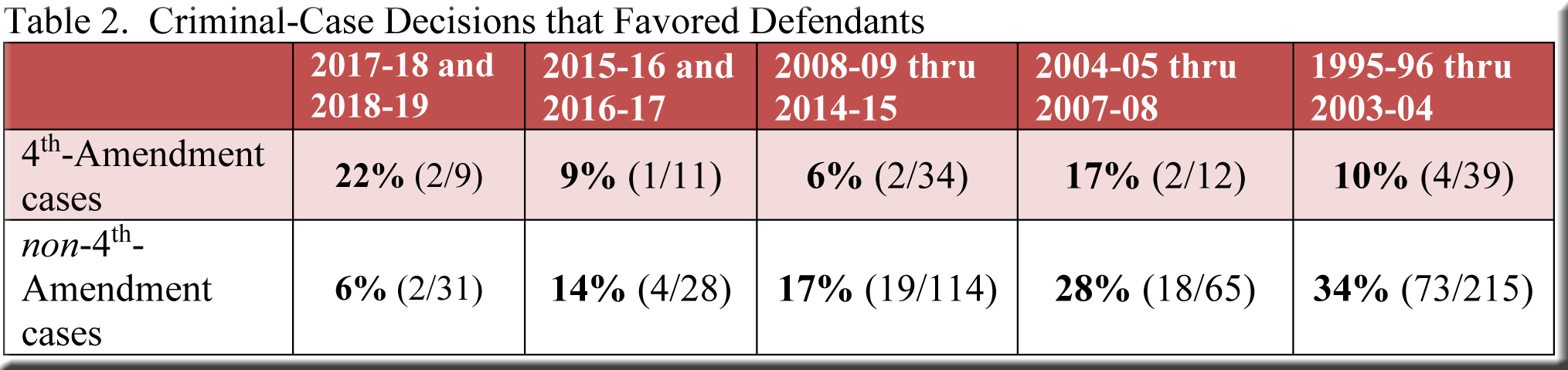

Meanwhile, a more dramatic change occurred in the percentage of Fourth-Amendment decisions favorable to defendants in criminal cases. As the court turned more conservative following the electoral defeat of Justice Butler by Justice Gableman, defendants encountered a frostier reception for their Fourth-Amendment arguments than during the “Butler years” (2004-05 through 2007-08). This outcome could not have astounded court watchers, but they were much less likely to have anticipated the results from the last two terms. First of all, as displayed in Table 2, the justices accepted Fourth-Amendment defenses more frequently during these two terms than they did during the “Gableman years”—and even during the “Butler years.”[1]

To be sure, the success rate for defendants in Fourth-Amendment cases was still only 22% in the interval spanning 2017-18 and 2018-19, but this was three times the rate for the period 2008-09 through 2016-17. Moreover, while the success rate in Fourth-Amendment criminal cases spiked during the last two terms, it plunged for criminal defendants in non-Fourth-Amendment cases. Table 2 reveals that throughout the period from 1995-96 to 2016-17, defendants in non-Fourth-Amendment cases had better odds than did their counterparts who advanced Fourth-Amendment arguments. But not during the two most recent terms, when defendants in non-Fourth-Amendment cases prevailed only 6% of the time. This is remarkably low, even when compared to the rate for the “Gableman years,” and it contrasts vividly with the Fourth-Amendment success rate that jumped to 22%.

Votes by Individual Justices

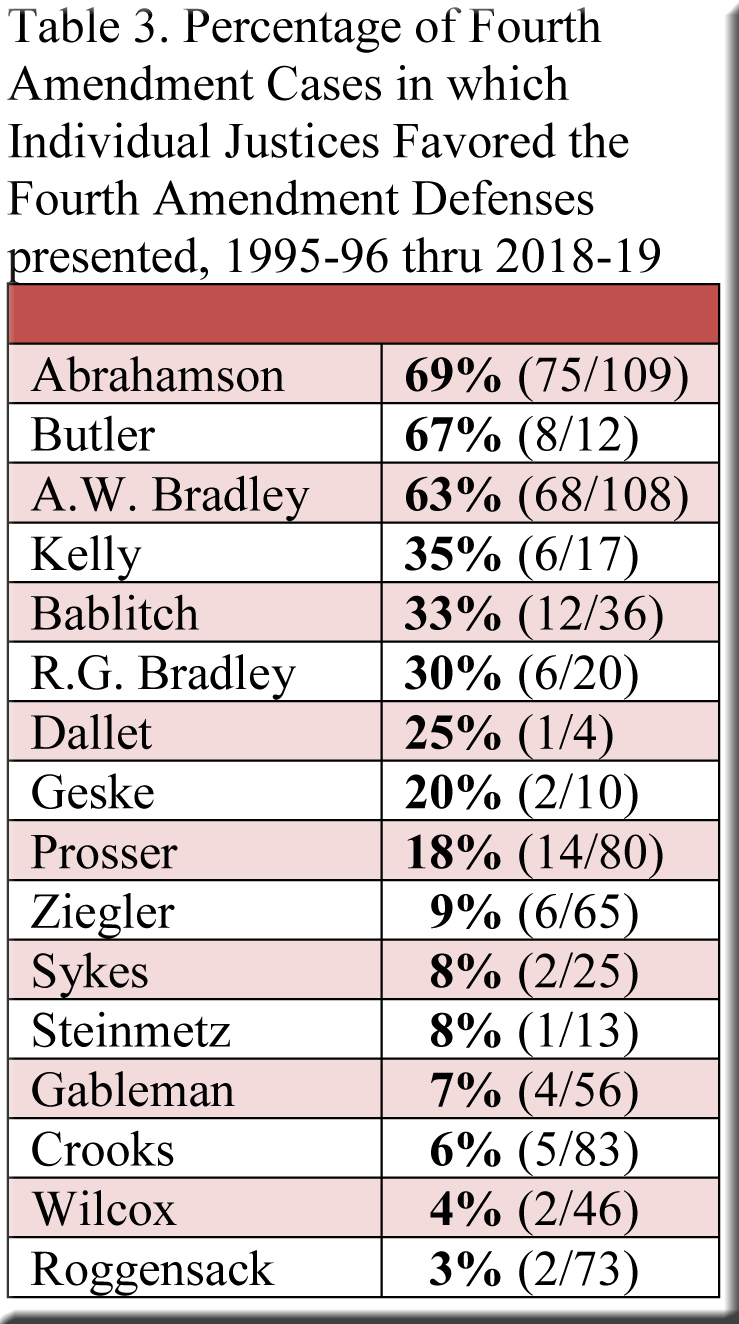

Table 3, which shows individual justices’ responses to Fourth-Amendment arguments, presents fewer surprises.[2] Liberals at the top; conservatives at the bottom. As in the preceding update, Justice Kelly’s location near the top may raise the most eyebrows, because, in cases of all types taken together, he has voted with the other conservatives over 80% of the time. However, his Fourth-Amendment percentage has dropped slightly since 2016-17, while Justice Rebecca Bradley’s has crept upward, leaving a smaller gap between them than before. Both of their percentages far exceed those of the court’s most ardent conservatives (Justices Ziegler and Roggensack), and they even register above the figure for Justice Dallet—though her first-term sample is too meager to support confident assessment.

OWI and Drug Cases

Perhaps the most striking change in the court’s Fourth-Amendment docket over the past two and a half decades appears in the following graph. It demonstrates that, for nearly the entire period, the underlying charges in these cases involved drug offenses (possession or distribution) much more often than drunk driving (OWI). The figures in the graph are calculated in three-year clusters, and during the first six years, over 80% of all Fourth-Amendment cases encompassed drug charges, while OWI offenses spawned less than 10%.[3] The substantial distance between the graph’s two lines endured all the way down to the penultimate cluster, when they finally crossed. By the end, Fourth-Amendment cases were more than twice as likely to emanate from OWI offenses as from drug charges.

Conclusion

It will be interesting to discover how the lines on this graph behave over the next few years. For instance, the recent flurry of OWI cases has centered most often on disputed blood draws. If the court comes to regard this issue as settled, the volume of OWI cases may sink back to its previous level.

We’ll also learn more about Justice Dallet’s views on Fourth-Amendment defenses. Will her votes remain similar to those of Justices R.G. Bradley and Kelly, as they were in her first term, or will they approach those of Justice A.W. Bradley? And what about the newest member of the court, Justice Hagedorn? Although no one expects to sight him lodged at the top of Table 3, it is yet unclear whether he will alight closer to Justices R.G. Bradley and Kelly in Fourth-Amendment cases, or occupy more common ground with Justices Roggensack and Ziegler. In our next update, we shall see.

[1] Per curiam decisions are omitted. There are a small number of “gray-area” cases (including State v. Brian Grandberry from the 2017-18 term) that I have not categorized as Fourth-Amendment decisions. For more, see footnote 1 of the previous update.

[2] The table includes a handful of non-criminal Fourth-Amendment cases. I have omitted Justice Roland Day from the table, because it covers only the last year of his long tenure (1974-96) on the court.

[3] The remaining Fourth-Amendment cases arose from a variety of other charges, such as homicide, robbery, bail jumping, possession of child pornography, and possession of a firearm by a felon. Click here for a table that shows the percentage of these “other” charges, along with those for drugs and OWI, during the years covered by the graph.

[…] still on the court and Justices R.G. Bradley and Kelly had recently joined. Today SCOWstats posted another update through the end of the 2019 term, which included Justice Dallet. Surprise! The 4A is not DOA in […]