We now have opinions by two new justices and decisions from three more terms (2014-15 through 2016-17) to add to our initial discussion of Fourth Amendment cases, so it’s time for an update.[1] A number of recent developments are noteworthy, including the growing portion of the docket devoted to Fourth Amendment cases, which represented a larger percentage of the court’s cases during the past three years than in any other three-year period of the 22 terms under consideration. As shown in Table 1, the 2016-17 term surpassed all others in this regard, when 18% of the court’s decisions addressed Fourth Amendment arguments, and the second highest figure (15%) was recorded in 2014-15. In broader perspective, the six highest percentages all came during the last nine terms, when the court’s share of Fourth Amendment cases (10%) doubled the average for the previous 13 terms.[2]

(click on tables to enlarge them)

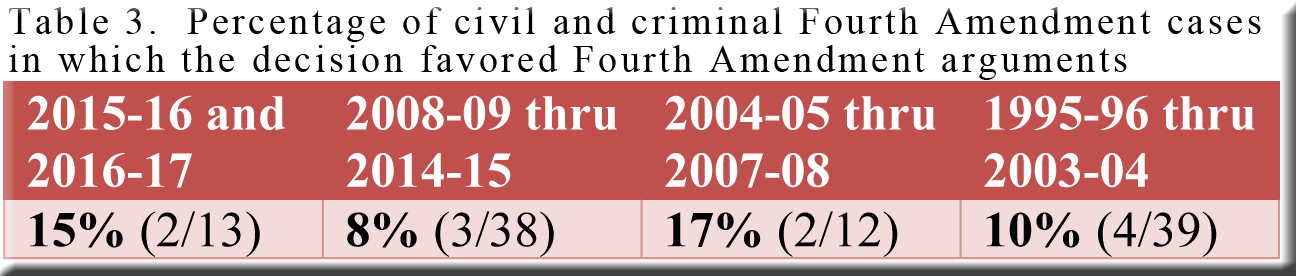

These last nine terms have coincided with Justice Gableman’s tenure on the court, which began when he replaced Justice Butler in 2008-09. Given the court’s more conservative bent thereafter, one might expect that Fourth Amendment arguments were received less sympathetically, and this has been the case (at least for most of the period, as explained below). During the seven years from 2008-09 through 2014-15, when the court’s composition remained unchanged,[3] the justices favored Fourth Amendment arguments in only 8% of their decisions—well below the figure of 17% during the four “Butler years” and slightly lower than the 10% during the nine terms before Justice Butler joined the court.

If we focus only on criminal cases—that is, omit such cases as the “John Doe” batch from 2015 (when the court’s majority accepted Fourth Amendment arguments in order to terminate a search for evidence that Governor Scott Walker’s campaign and various conservative groups had violated campaign finance laws) and a tax case in 2017 (when the court ruled that the Fourth Amendment allowed homeowners to challenge their tax assessments without permitting assessors to inspect the interiors of their homes)—we find that the court’s recent distaste for Fourth Amendment arguments has been even more pronounced.[4] From 2008-09 through 2014-15, the justices favored Fourth Amendment arguments in only 6% of criminal cases, compared to 12% of such cases from 1995-96 through 2007-08, and 17% during the four “Butler terms” at the end of this period. As noted in the earlier post, and in Table 2 here, defendants in non-Fourth-Amendment criminal cases had a good deal better (though still not great) chance of prevailing than did defendants in criminal cases involving the Fourth Amendment.

However, Table 2 also suggests that during the two most recent terms, when Justices Rebecca Bradley and Daniel Kelly replaced Justices Crooks and Prosser, the court has grown more receptive to Fourth Amendment arguments than it has been since the four “Butler terms” ending in 2007-08—a supposition that is even more plausible when civil and criminal Fourth Amendment cases are considered together, as in Table 3.[5]

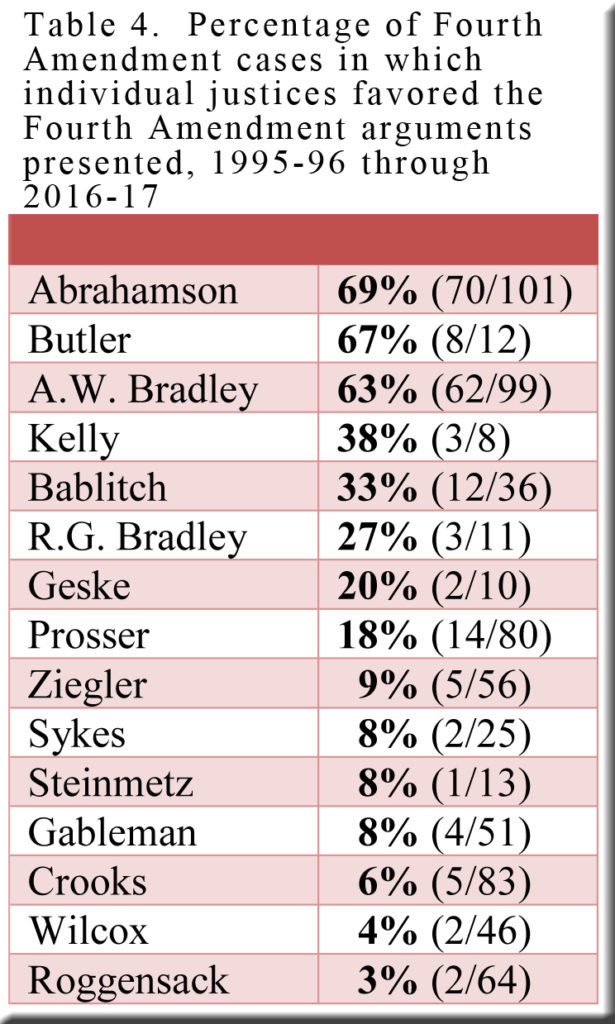

Of course, the set of votes cast by Justices R. Bradley and Kelly is still so small that this early impression will need to be checked against the results from subsequent terms. Up to this point, though, the two newest justices have been much more inclined to favor Fourth Amendment arguments than were their two predecessors. As displayed in Table 4, Justices Crooks (6%) and Prosser (18%) accepted Fourth Amendment arguments at a substantially lower rate than have Justices R. Bradley (27%) and especially Kelly (38%). Indeed, both Justices R. Bradley and Kelly are in the top half of Table 4, along with the court’s most “liberal” members—and far above Justices Ziegler (9%), Gableman (8%), and Roggensack (3%).[6] If, during the next few terms, the court does continue to endorse Fourth Amendment arguments more readily than it did from 2008-09 through 2014-15, the impact of these personnel changes will have been an important factor.

Meanwhile, two cautions bear repeating. First, uncertainties stemming from the small number of decisions filed during a two-year period demand restraint in identifying “trends,”[7] and, second, despite the recent “trend” discussed above, the court has remained distinctly unsympathetic toward Fourth Amendment arguments in criminal cases. As yet, there are no grounds for disputing Justice Ann Walsh Bradley’s observation that “[i]n the last two terms, this court is batting nearly zero when it comes to upholding Fourth Amendment challenges in criminal cases.”[8] Although some might consider this a desirable outcome, Justice Bradley’s position in Table 4 leaves no doubt as to her regret over the feeble protection currently afforded defendants in Fourth Amendment cases.

Moreover, she has concluded that the court appears to be moving toward a double standard in these cases—indulgent on the comparatively prosperous, and severe on the non-white and relatively poor. Dissenting in 2016 (along with Justice Abrahamson) in State v. Dumstrey, she complained that “[t]he majority’s application of the Fourth Amendment’s protections creates a great inequity among the people of Wisconsin. … [U]nder the majority opinion, the protections of the home now apparently depend on whether an individual lives in a single-family or multi-family dwelling.” A year later, in State v. Floyd (again joined by Justice Abrahamson), she was blunter: “I write also to express my concern that the majority opinion, in lockstep with this court’s jurisprudence, continues the erosion of the Fourth Amendment. It is through such erosion that implicit bias and racial profiling are able to seep through cracks in the Fourth Amendment’s protections.”

While observers could not have been surprised to find the court’s two “liberals” worrying that Fourth Amendment decisions might have the effect of targeting racial minorities, I suspect that no one was anticipating anything of the sort from the other five justices as the court prepared to file its last batch of decisions this summer. Consider, then, State v. Navdeep Brar, which involved a defendant arrested for driving while intoxicated and whose blood was drawn for testing, without a warrant. Along with the issue of whether he had given verbal consent for this blood draw, the court addressed the question of whether his consent was required at all. In other words, does Wisconsin’s Implied Consent Law, by itself, eliminate Fourth Amendment objections to warrantless blood draws from people arrested for operating under the influence? Justice Roggensack’s lead opinion answered both questions in the affirmative.

Justice Kelly did not, and he offered an explanation in a “concurrence” that must have seemed rather truculent to Justice Roggensack. After agreeing that this particular defendant had freely given verbal consent to the warrantless blood draw, Justice Kelly proceeded to argue—at length and with fervor—that the legislature must not be allowed to automatically annul citizens’ constitutional rights. Justice Roggensack’s lead opinion did just that, he maintained, by permitting the legislature to suspend citizens’ Fourth Amendment rights whenever they go for a drive. He then wondered what other statutes could follow through this door that the court had swung open. Perhaps a law stating that citizens also consented to waive their Sixth Amendment right to counsel, if arrested while driving? His list of hypotheticals concluded with this: “There are certain parts of the State that experience a disproportionate amount of crime. Perhaps the legislature might decide police need greater access to homes and other buildings in such areas.” The court’s new ruling, he observed, would enable the legislature to adopt an “implied consent” law stipulating that people recording property deeds in designated neighborhoods agreed automatically to a search of their property if the police suspected their involvement in a crime. “It takes very little imagination to see how this new doctrine could eat its way through all of our constitutional rights.”

To be sure, the divergence between Justice Kelly and Justice Roggensack can easily be overstated. After all, he joined her in 85% of the court’s decisions during the 2016-17 term. Nevertheless, if presented with an unattributed passage expressing vigorous concern that the court had signaled its acceptance of future legislation targeting citizens likely to be racial minorities, one would almost certainly credit authorship to Justices Abrahamson or A.W. Bradley—but not to Justices Roggensack, Ziegler, or Gableman, the court’s established “conservatives.” In short, Justice Kelly’s choice of hypotheticals in State v. Brar and, more broadly, his comparatively-frequent approval of Fourth Amendment arguments (Table 4) distinguish him sharply from other members of the “conservative” fold.

Thus, if one were asked to predict who might emerge, if only occasionally, as a maverick among the court’s five “conservatives” in the upcoming term, the most conceivable candidate could well be Justice Kelly, and a promising place to look for evidence of this would be his separate opinions in Fourth Amendment criminal cases.

[1] Included in this study are cases in which the majority/lead opinion addressed arguments pertaining to the Fourth Amendment (and Article I, Section 11 of the Wisconsin Constitution). I am excluding a small number of cases where (1) the petitioner offered a Fourth-Amendment argument, but the court decided the case on other grounds (e.g., State v. Popenhagen); (2) the Fourth Amendment figured only tangentially (e.g., State v. Zamzow) or was addressed in a separate opinion but not in the majority/lead opinion (e.g., State v. Stietz); or (3) the court filed a per curiam decision.

Also, I am not categorizing a few separate opinions where (1) a justice declared that a Fourth Amendment argument addressed in the majority/lead opinion need not be raised in order to resolve the issue before the court; or (2) it was difficult to categorize the separate opinion as “for” or “against” the Fourth Amendment argument in the majority/lead opinion.

[2] Of these six highest percentages, the lowest (9%) occurred not only in 2015-16 but also in 1999-00.

[3] Justices Abrahamson, A.W. Bradley, Crooks, Prosser, Roggensack, Ziegler, and Gableman.

[4] In this paragraph and in Table 2, the term “criminal cases” refers to cases whose numbers end in the CR suffix. This excludes a handful of collateral attacks that might lack a CR suffix, but these are so few in number as to have no significant impact on the calculations in this post. Also excluded are an even smaller number of decisions that were difficult to characterize as either favorable or unfavorable to the defendant.

[5] The court’s growing receptiveness to Fourth Amendment arguments in criminal cases during the last two terms is all the more notable because, at the same time, the justices ruled less frequently for defendants in non-Fourth-Amendment criminal cases.

[6] I have omitted Justice Roland Day from Table 4, because the table covers only the last year of his long tenure (1974-96) on the court.

[7] Justice Kelly presents the greatest challenge here, partly because he has participated in fewer cases than the other justices, and partly because his comments on the Fourth Amendment were difficult to categorize in two instances. More specifically, in State v. Howes his two-sentence concurrence announced support for Justice Roggensack’s lead opinion “in toto as well as the mandate of the court,” because he agreed that under the exigent circumstances doctrine, the warrantless blood draw in question did not violate the Fourth Amendment. Justice Abrahamson rejected this exigent-circumstances argument and authored a dissent. Justice Kelly joined Part II of her opinion, which included the following assertion: “I conclude that the statute’s unconscious driver provisions are unconstitutional because unconscious drivers have not freely and voluntarily consented to the warrantless blood draw under the Fourth Amendment. Therefore, the warrantless blood test in the instant case should be suppressed.” In the end, I decided not to include Justice’s Kelly’s concurrence in State v. Howes in this post’s tables, because it did not seem clearly favorable or unfavorable toward Fourth Amendment arguments. If I had labeled his concurrence as “favorable,” his percentage in Table 4 would have risen from 38% to 44% (4/9), while an “unfavorable” label would have dropped it to 33% (3/9)—still far above the figures for Justices Roggensack, Ziegler, and Gableman.

In another case (State v. Brar) that also involved a warrantless blood draw, I chose to categorize Justice Kelly’s concurrence as favoring a Fourth Amendment argument. Although he joined the court’s mandate and accepted Justice Roggensack’s conclusion that the defendant had expressly consented to the blood draw, this point was overshadowed, in my opinion, by the extended and forceful nature of his discussion of the “implied consent” provision, which consumed most of his 26-page concurrence (and eclipsed the level of engagement in his two-sentence concurrence in State v. Howes filed a few months earlier). See below for more on Justice Kelly’s concerns in State v. Brar.

[8] Justice Bradley’s dissent (joined by Justice Abrahamson) in State v. Floyd, filed July 7, 2017.

I was stopped for stop sign violation. I handed out my license, proof of insurance and registration. Here is what happened. Knowing that Miranda is not read during a detainment and knowing that anything you say can be held against I chose to remain silent. That became “suspicious behavior” which then leads to probable cause and thus ends your fourth amendment rights. Don’t believe me, how about a police video that I am lucky to have survived after being thrown across the street. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0mfkacPAJE4 IS THIS RIGHT CONSTITUTIONALLY??

Our fourth, fifth and sixth amendments are being reinterpreted and redefined by a supreme court system that consistently puts us in more and more danger. I am a big advocate of TERM LIMITS for all elected officials including misdemeanor and common plea judges who rule for a life time because most people vote incumbent allowing judges to rule with immunity and impunity.