Last fall’s post on the Fourth Amendment found that (1) these cases have accounted for a growing portion of the court’s output in recent years, and (2) the court’s two newest members (Justices R.G. Bradley and Kelly—especially Justice Kelly) have been more receptive to Fourth Amendment arguments than were the two justices (Crooks and Prosser) whom they replaced. The second point doubtless goes some way toward explaining why the court has accepted Fourth Amendment arguments in criminal cases more readily during the last two terms than it did from 2008-09 through 2014-15 (although it remains more hostile to such defenses than it was before Justice Gableman joined the bench in 2008-09).

Could something of the sort have happened as well with Sixth Amendment decisions, which reach the court as often as their Fourth Amendment cousins? These cases focus on a defendant’s right to a fair trial—more specifically, the right (1) to have a prompt and public trial, with an impartial jury, (2) to know the nature of the charges and the identity of one’s accuser, (3) to confront adverse witnesses, (4) to testify and present witnesses on one’s behalf, and (5) to have a competent lawyer. Today we’ll turn the spotlight on the Sixth Amendment and see if the arrival of Justices R.G. Bradley and Kelly has coincided with developments similar to those summarized above for Fourth Amendment decisions.[1]

In one respect, the same script has applied to Fourth and Sixth Amendment decisions, as both have been consuming more of the court’s docket of late. Fully 20% of the decisions filed in 2016-17 included Sixth Amendment arguments, larger than the share for any of the other 21 terms under consideration.[2] In fact, as shown in Table 1, the six highest percentages have all clustered in just the last eight years—an even more striking concentration than that apparent for Fourth Amendment cases (for which the six highest percentages came during the last nine terms).[3]

(click on tables to enlarge them)

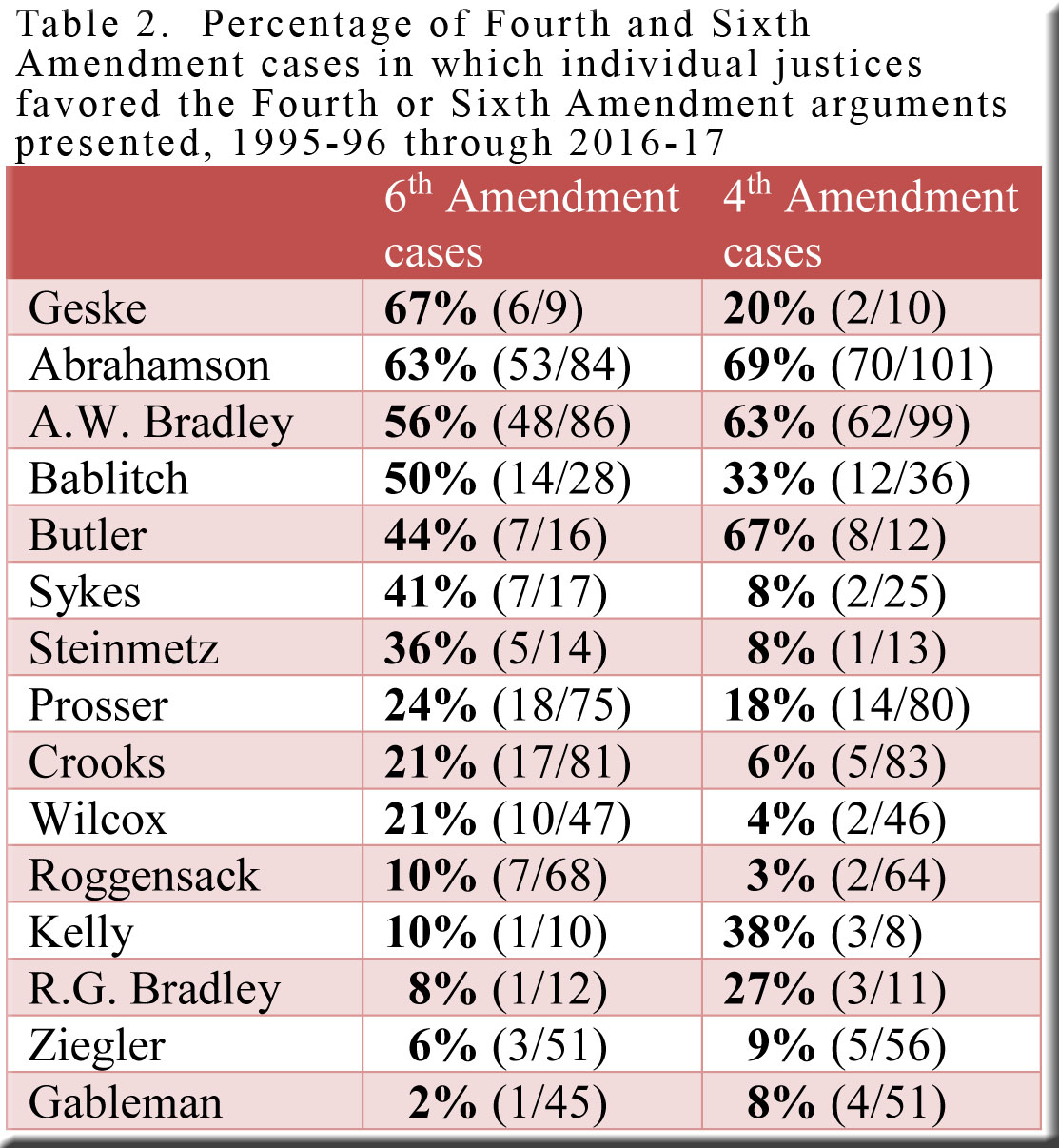

However, at this point our Sixth Amendment findings part company with those from the previous post on the Fourth Amendment. While Justices R.G. Bradley and particularly Kelly have been more sympathetic to Fourth Amendment arguments than were Justices Crooks and Prosser, the two newcomers have given Sixth Amendment defenses a much chillier reception than did their two predecessors (Table 2)—and they have done so in lock step.[4] Their only embrace of the Sixth Amendment occurred in State v. Stietz, where the court reversed the conviction of a man accused of holding two conservation wardens at gun point, even after he understood that the two men were law enforcement officers. Although the majority opinion (by Justice Abrahamson) did not address a Sixth Amendment claim, Justice Bradley’s concurrence, joined by Justices Kelly and Roggensack (but rejected by Justices Ziegler and Gableman) maintained that Stietz was denied his Sixth Amendment right to present in his defense the argument that the wardens were allegedly trespassing on his property.

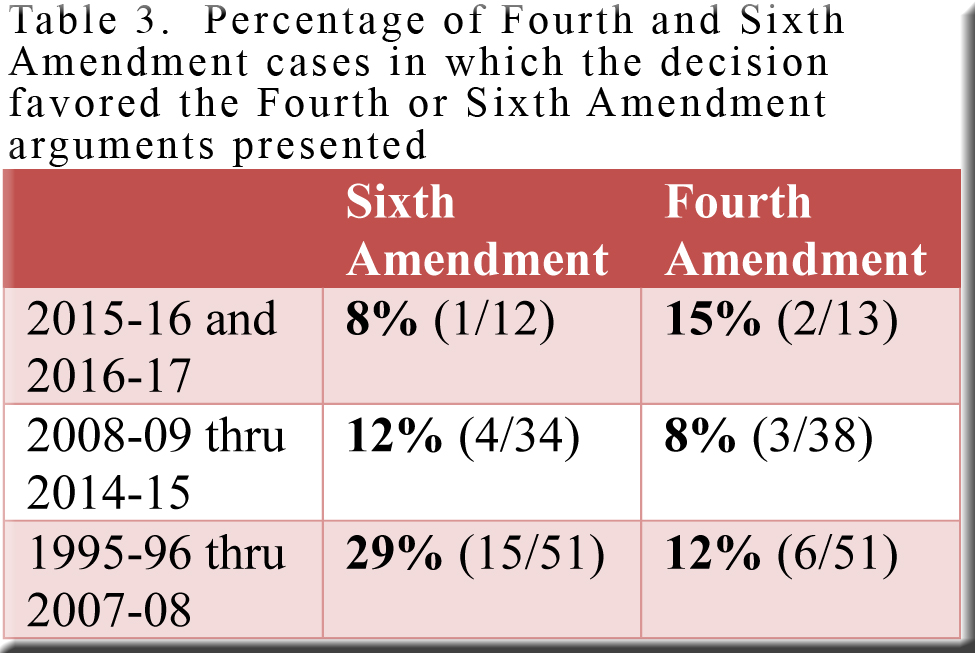

Not only have Justices R.G. Bradley and Kelly found Sixth Amendment arguments less persuasive than their Fourth Amendment counterparts, so has the court as a whole during these same two terms. This marks a departure from the norm of the preceding 20 years, when defendants’ chances of prevailing were less discouraging with Sixth Amendment than with Fourth Amendment arguments. It may well be that the arrival of Justice R.G. Bradley, followed the next year by Justice Kelly, helped account for this change.

As displayed in Table 3,[5] decisions accepted Sixth Amendment arguments just 8% of the time during the two most recent terms, and one could argue that the figure should be lowered to 0% (0/11) by omitting State v. Lynch. In Lynch, the justices reviewed a court of appeals decision affirming Lynch’s contention that the Sixth Amendment guaranteed him the right to examine certain privileged information that might bolster his defense. When the dust had settled, the supreme court filed a “lead opinion” that would have reversed the court of appeals—except that it drew support from only three justices. With no combination of four justices able to agree on a ruling, the outcome left the court of appeals holding in place. As a result, I have classified Lynch as a decision favoring the Sixth Amendment, but the supreme court’s endorsement was so feeble that the case could be removed from consideration with no objection from me.

It’s worth noting that the number of Sixth Amendment (and Fourth Amendment) cases decided in just two terms is rather small—and still less for Justice Kelly, on the bench only since 2016-17. We will need to follow the voting of Justices R.G. Bradley, Kelly, and their colleagues over the next few years in order to determine whether the developments discussed above can be interpreted as the early stages of more persistent trends.

[1] Today’s post updates one that appeared in November of 2015 (“The Fate of Sixth-Amendment Arguments”), which covered the period from 1995-96 through 2014-15.

[2] To locate cases, I searched decisions for the words “Sixth Amendment.” I then checked each decision in the search results to make sure that a Sixth Amendment argument was actually advanced (as opposed to, say, a parenthetical mention of the amendment that did not pertain directly to the argument at hand). When a case included multiple issues, I focused only on those involving the Sixth Amendment.

In rare instances, a majority opinion presented a ruling on a Sixth Amendment argument together with other arguments, while a dissenting opinion addressed only the non-Sixth Amendment arguments. Here, I counted the justices in the majority as voting on the Sixth Amendment argument but did not record the votes of the dissenting justices (rather than attempt to interpret their silence on the Sixth Amendment issue).

If a decision concluded that the Wisconsin Constitution affords greater protection than does the Sixth Amendment to the US Constitution, I included the case.

Occasionally the court agreed that a petitioner’s Sixth Amendment rights had been violated, but decided that the error was “harmless”—thereby declining to overturn the petitioner’s conviction. Such outcomes are categorized here as “unfavorable” toward the Sixth Amendment argument presented by the petitioner.

I generally excluded a small number of cases that fell into certain gray areas such as the three examples that follow. (1) On rare occasions a decision stated that if certain “facts” were indeed true, the defendant might be able to prevail on a Sixth Amendment claim. However, being unsure on this score, the court remanded the case for a more thorough assessment of the “facts” in question. (2) In a few cases, a defendant argued ineffective assistance of counsel (a Sixth Amendment issue), but the dispute before the court involved only the proper time or forum for such a determination, with no assessment of the validity of the argument itself. (3) Just as infrequently, both parties briefed a Sixth Amendment issue, but the majority opinion decided the case on other grounds—thus, not a Sixth Amendment case for our purposes. If, however, a separate opinion did address the Sixth Amendment issue, I counted the author(s) of the separate opinion(s), but not the other justices.

People may differ reasonably on how to handle one gray area or another, and there will always be a few cases whose specific features frustrate easy categorization, regardless of the gray-area procedure adopted. In any event, the number of borderline cases is small enough that any judicious gray-area approach will have little or no effect on the percentages presented above.

All of the decisions may be found on the court system’s website.

[3] In the corresponding Fourth Amendment table contained in last autumn’s post, the total number of decisions filed each year included per curiam decisions. Hence the slight difference in yearly totals in that Fourth Amendment table and the Sixth Amendment table displayed here.

[4] Justice Roland Day is not included in Table 2 because the data cover only his last term on the bench (1995-96).

[5] The figures in Table 3 include both civil and criminal cases.

Speak Your Mind