After a decade and a half of relatively frequent turnover, the supreme court’s membership did not change from 2008-09 through 2014-15. During these seven terms, the justices were often placed along a spectrum that included two “liberals” (Justices Abrahamson and Ann Walsh Bradley) and three “conservatives” (Justices Roggensack, Ziegler, and Gableman), with the remaining justices (Crooks and Prosser) situated between these two groups, but closer to the “conservatives.”

Over the next two years, though, the death of Justice Crooks and the retirement of Justice Prosser brought two new justices (Rebecca Bradley and Daniel Kelly) to the court—and raised the question of how their voting has compared with that of the justices whom they replaced. Have they occupied roughly the same position on the spectrum as Justices Crooks and Prosser, or has their presence contributed to significant changes in the court’s voting patterns? Posts currently under consideration may explore this question with regard to specific issues or categories of cases, but today we offer a broader examination of the four justices’ votes.

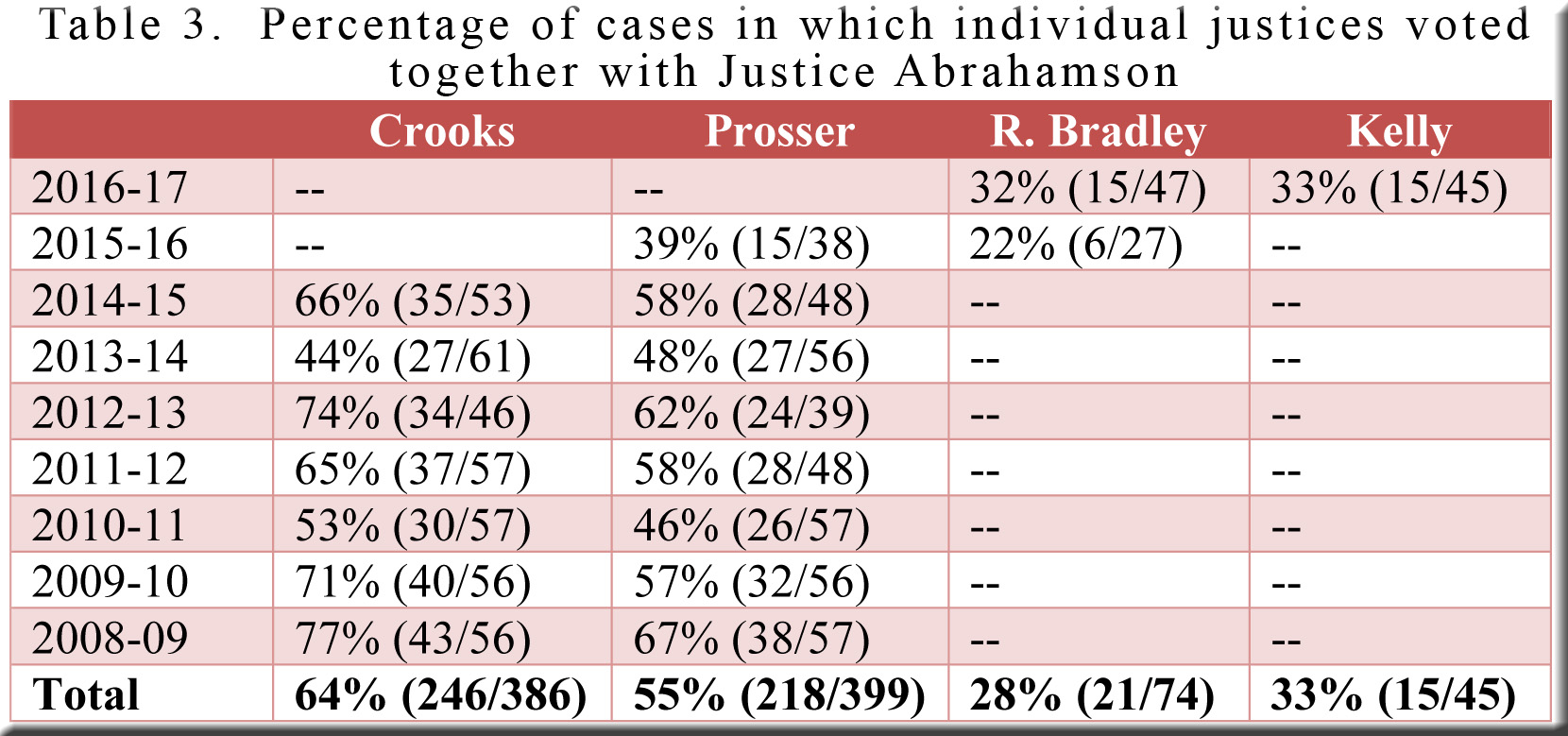

It should be emphasized that the number of votes cast by the two newcomers is still very small—especially in the case of Justice Kelly, who has just completed his first year on the bench. Consequently, the impressions created by the following tables must be viewed as preliminary, perhaps as hypotheses to be measured against voting records from subsequent terms. With that in mind, then, let’s turn to some of the ways in which the voting of Justices Crooks/Prosser compares with that of their two successors.

In certain respects, scarcely any change occurred—notably in the frequency with which Justices Crooks, Prosser, R. Bradley, and Kelly voted in agreement with the court’s three established “conservatives” (Justices Roggensack, Ziegler, and Gableman). Table 1, for instance, reveals that each of the four justices voted together with Chief Justice Roggensack (either both in the majority or both dissenting) at almost exactly the same rate—Justice Crooks aligned with her in 86% of decisions, Justice Prosser 85%, Justice R. Bradley 85%, and Justice Kelly 85%.

(click on graphs and tables to enlarge them)

The match was also very close between our quartet and Justices Ziegler and Gableman.[1] Given these results, we could readily predict that Justices R. Bradley and Kelly would vote with the majority at nearly the same rate as did Justices Crooks and Prosser—which they have, so far, as detailed in Table 2.

In other respects, however, the differences between Justices Crooks/Prosser and Justices Bradley/Kelly are more pronounced. Consider, for example, the frequency with which Justices Crooks and Prosser voted together. From 2008-09 through 2014-15, the pair cast votes in 364 decisions and sided with each other in 304 of them—or 84% of the time. Although this figure demonstrates extensive agreement between the two men, it also suggests that court watchers did not find it remarkable when these justices disagreed, as they did in 60 cases. The same cannot be said for Justices R. Bradley and Kelly, who have voted together in near lock step—on the same side 98% of the time (in 43 of the 44 cases where both participated). To be sure, Justice Kelly has voted in only one term, and he may yet compile a voting record clearly distinct from that of Justice Bradley, but, so far, Justices Bradley/Kelly are a more homogenous pair than were Justices Crooks/Prosser.

The contrast between these two sets of justices is particularly vivid when we compare how frequently each voted in agreement with the court’s most “liberal” member, Justice Abrahamson. In Table 3, we find that Justice Crooks sided with Justice Abrahamson in 64% of their votes since 2008-09, and Justice Prosser did so 55% of the time—far above the figures for Justice R. Bradley (28% over the last two terms) and Justice Kelly (33% in 2016-17).[2]

Indeed, the court’s two newcomers have been no more inclined than the three established “conservatives” (Justices Roggensack, Ziegler and Gableman) to vote with the court’s two “liberals.” We have seen in Table 3, for instance, that Justice R. Bradley sided with Justice Abrahamson 28% of the time, and that Justice Kelly did so in 33% of the votes that he cast. Over the same two terms, Justices Roggensack, Ziegler and Gableman voted together with Justice Abrahamson 35%, 33%, and 38% of the time respectively.[3] Thus the replacement of Justices Crooks (especially) and then Justice Prosser by Justice R. Bradley (especially) and then Justice Kelly helps explain the surge in the percentage of 5-2 decisions during the last two terms (displayed in the following graph)—with Justices Abrahamson and A.W. Bradley isolated as the two minority votes in four-fifths of these outcomes.[4]

Looking ahead, one wonders which (if any) of the impressions sketched above might change in the years to come. Will Justices R. Bradley and Kelly generate voting records that are more distinct from one another? More distinct from those of the established “conservatives”? Or (slightly) less at odds with the votes cast by the court’s “liberals”? It seems likely that these three outcomes are linked, so that if any one of the changes occurs, it will affect answers to the other two questions as well. But patience is required, as more voting data must accumulate in order to permit confident conclusions.

[1] Click here for a table showing the percentage of cases in which each of the four justices voted together with Justice Gableman.

[2] Although the gap is not quite as striking, there is also a substantial difference between the frequency with which the two pairs of justices sided with the court’s other “liberal,” Justice Ann Walsh Bradley. Click here for a table.

[3] Justice Kelly, of course, participated in only the second of these two terms. Here are the percentages of votes in which the following justices sided with Justice Ann Walsh Bradley during the last two terms: Roggensack (39%), Ziegler (38%), Gableman (43%), R. Bradley (32%), and Kelly (41%).

[4] The graph includes a small number of 4-2 decisions. As shown by the graph, 5-2 decisions amounted to 60% of all decisions filed in 2015-16 and 50% of those filed in 2016-17. Compare these figures to those for the preceding 31 terms, when 5-2 decisions averaged only 17% of all decisions filed. For the period 1984-85 through 2007-08 the average was only 13%, and over the period 2008-09 (when Justice Gableman replaced Justice Butler) through 2014-15, it was 30%. During these earlier terms in the “Gableman years,” Justices Abrahamson and A.W. Bradley also accounted for most of the minority votes in 5-2 decisions, but, as noted above, these decisions did not occur as frequently as they did in 2015-16 and 2016-17.

Speak Your Mind