“The amicus growth spurt is significant and shows no sign of slowing down,” observed two professors at William & Mary Law School in a post titled “The Amicus Machine.” Writing about the United States Supreme Court, they furnished compelling evidence of an amicus proliferation of dramatic proportions. In 2015-16, for instance, nearly every case before the justices included amicus briefs—863 in all, averaging 13 per case—roughly double the volume just two decades before. It did not seem farfetched to proclaim, as the authors did in their opening sentence, that “we are living in the age of the Supreme Court amicus.”

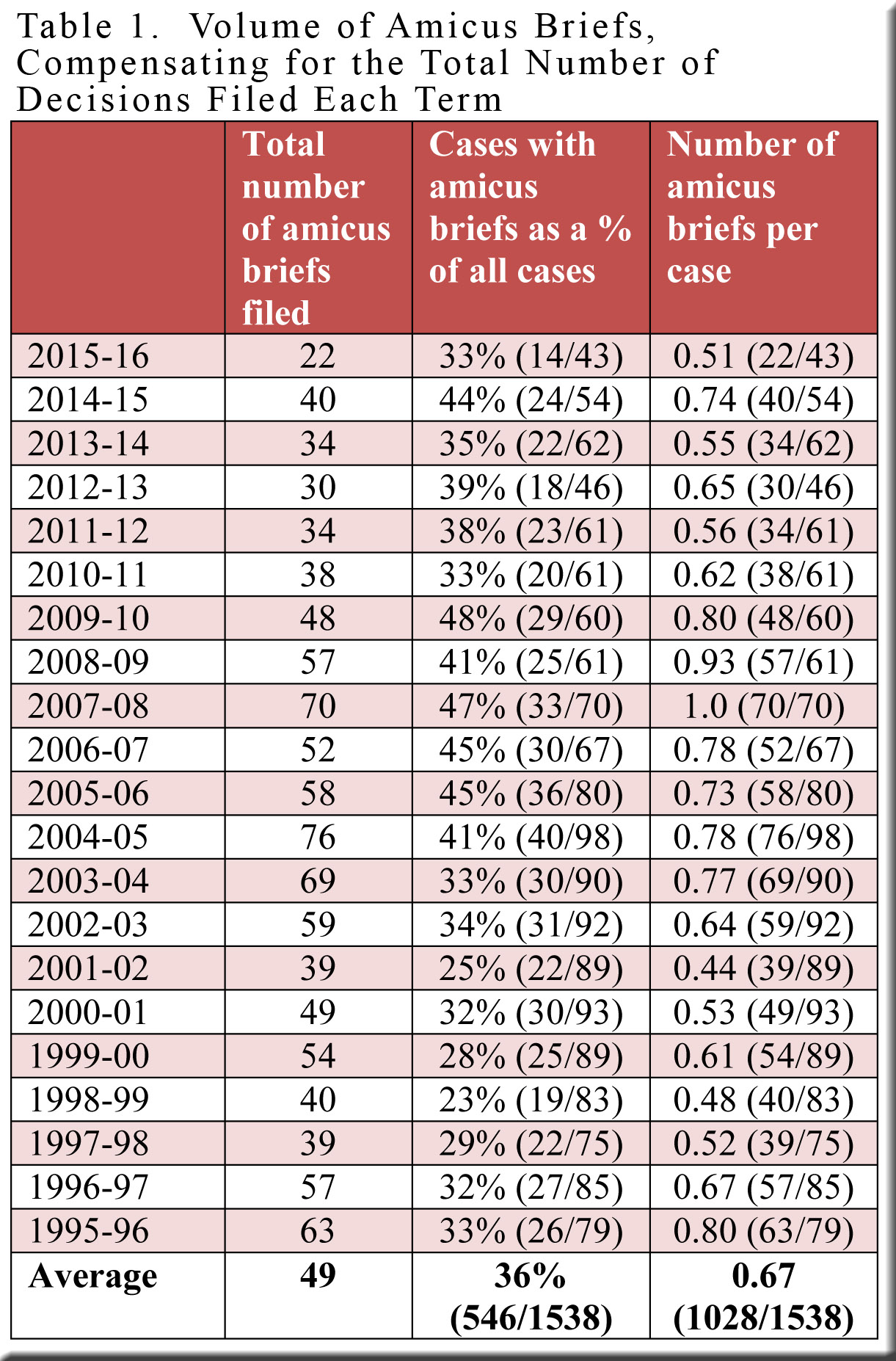

No such declaration could be made for Wisconsin, however, where data from the last two decades reveal the largest number of amicus briefs in the middle third of the period, followed by a precipitous decline thereafter, as apparent in the table below.[1] Thus, an Amicus Age may be resplendent at the US Supreme Court, but only a muted equivalent glimmered in Madison, and it quickly expired.

(click on graph and tables to enlarge them)

One might ask if the falling number of amicus briefs in Wisconsin over the past several years simply reflects the corresponding plunge in the number of decisions filed by the justices. It could still be possible, in other words, that the number of amicus briefs per case increased in recent years, or that the percentage of cases that included amicus briefs increased. Such developments, suggesting a role of growing importance for amicus briefs, would be masked by the sharp drop in the total number of cases decided by Wisconsin’s justices.

This hypothesis, while plausible, is also incorrect, as demonstrated in Table 1, which displays two ways of compensating for the declining number of decisions filed. More specifically, one can present cases with amicus briefs as a percentage of the total of all cases each term (column 3), and it is also a simple matter to calculate the average number of amicus briefs filed per case (column 4). In each instance, the highest values occur in the middle third of the period, while the numbers for the last half dozen years are nearly all lower.[2]

Why has the amicus sun dimmed in Wisconsin, preventing one from heralding anything like the Age of Amicus chronicled by followers of the US Supreme Court? No doubt the stakes seem higher in Washington, D.C., with far more money available to contest issues by funding amicus briefs. But such differences would not explain why amicus briefs in Wisconsin appeared more frequently in the past than they have of late. I will offer a conjecture on this question at the end of the post, but in the meantime, having set off down the amicus path, let’s examine some other points of interest.

Distribution

Table 2 provides a broad look at the distribution of amicus briefs among various categories of cases (which one could supplement with information gleaned from Table 6). To keep the venture manageable, our attention is confined to the last eight terms—a period throughout which all but the two newest justices have served together—and define “criminal cases” to include not only those whose numbers bear CR suffixes but also cases that feature collateral attacks on underlying criminal convictions (or, in a smaller number of instances, center in some other way on a prison inmate or a person accused of a crime).[3] With this understanding, “criminal cases” accounted for a quarter of all amicus cases, probably the largest single subset of the group. In the civil portion of the amicus pool, insurance cases and those involving the Wisconsin Realtors Association figured prominently, and they appear in Table 2 as well.[4]

Do they matter?

Another question hovering over a discussion of amicus briefs is their impact. Do they sway decisions? Although certainty on this score remains elusive in most cases, scholars are naturally reluctant to entertain the possibility that their prose is devoted to something of little importance. Hence the approach taken by the authors of “The Amicus Machine,” who observe that while “nobody can say for sure whether these briefs actually change case outcomes, it is clear that the justices are citing them regularly …”—in 54% of cases decided in 2015-16.

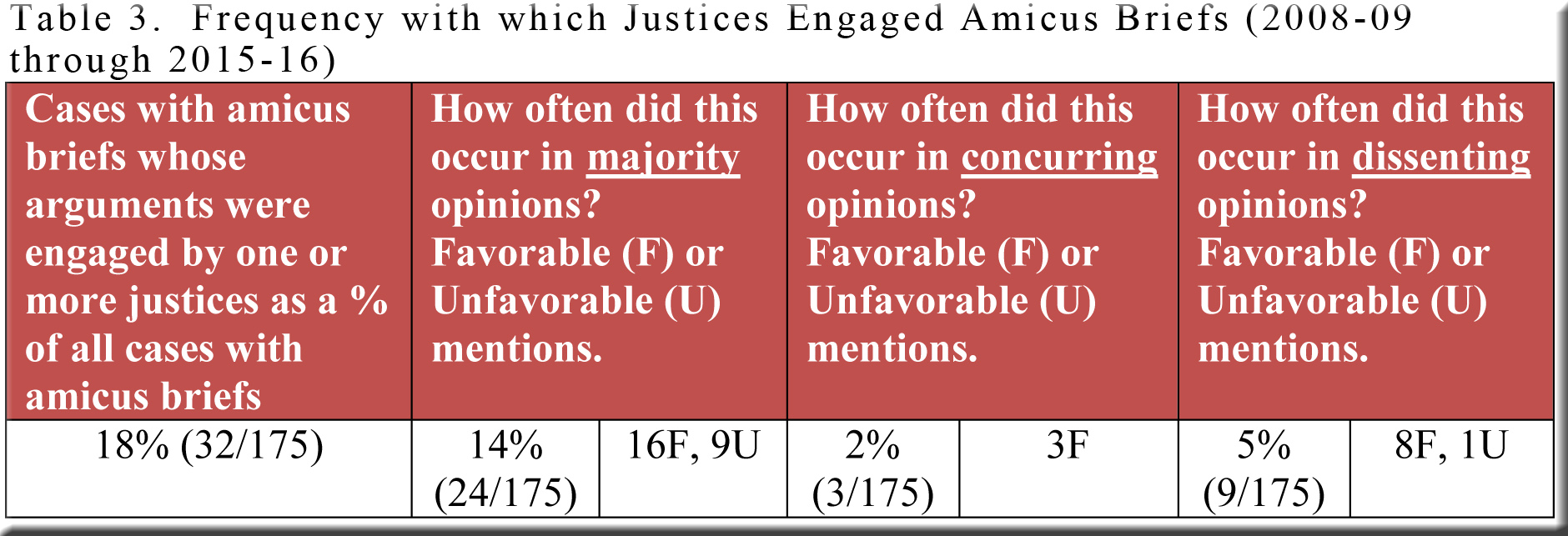

The same cannot be said of Wisconsin’s justices, who have engaged amicus briefs far less frequently. We’ll define the term “engaged” to mean something more than simply noting that an amicus brief was filed. To “engage” an amicus brief, a justice must address one or more of the brief’s arguments (either with approval or disapproval) or at least mention that the brief was helpful (or unhelpful) in providing background or context.[5] If we apply this understanding to the period 2008-09 through 2015-16, majority opinions engaged amicus briefs in a mere 14% (24/175) of cases in which the briefs were filed. In these 24 majority opinions, there were 16 favorable and 9 unfavorable mentions of the amicus contributions.[6] Justices also addressed amicus briefs in concurring and dissenting opinions, though even less often, as detailed in Table 3.

Who files?

There remains the question of who filed amicus briefs, and on whose behalf. Given that several hundred law firms and other organizations took turns in these roles over the last decade, they cannot all be named individually in this space. We’ll restrict our attention to the most active participants, so that only firms and institutions that filed at least 10 amicus briefs during this period made the cut and appear in Table 4.[7] Godfrey & Kahn (a majority of whose filings came on behalf of the insurance industry) towers above this group, with the Department of Justice and the Wisconsin Realtors Association also particularly energetic filers.

The information that generated Tables 3 and 4 can also tell us which filers of amicus briefs found their submissions engaged most frequently by the justices. To this end, Table 5 lists all firms and other organizations that filed at least two amicus briefs which justices chose to engage during the eight terms from 2008-09 through 2015-16. The table also indicates what percentage of a filer’s total number of amicus briefs were engaged—ranging from 7% of Godfrey & Kahn’s filings to 67% of those from Gass Weber Mullins.[8]

Table 6 includes all organizations on whose behalf at least five amicus briefs were filed since 2006-07.[9] The personal-injury bar, the criminal defense bar, the insurance industry, the realtors association, and the Department of Justice all figure conspicuously in the table, as one would expect from the foregoing discussion.

Conclusion

The abrupt decline of amicus briefs in Wisconsin may surprise anyone aware of the rising torrent washing through the United States Supreme Court—especially as permission to file such briefs is much simpler to gain in Madison than in Washington, D.C. Lacking a confident explanation for this development in Wisconsin, let me conclude with some speculation and a request for alternative theories from readers.

Consider the hypothesis that the justices’ decisions on various issues have become so predictable in recent years (whether a consequence of increasing polarization or other factors), that this trend bears more than a coincidental relationship with the drop in the number of amicus briefs filed during the same period. In other words, interested parties might be more inclined now to conclude that either (1) they will get a desirable decision or (2) it is hopeless to expect one, whether or not they file an amicus brief. If such a conclusion has been reached more often of late, it would encourage potential filers of amicus briefs in Wisconsin to favor other uses of their resources. This may not be a matter of concern to the justices, but should they come to desire additional amicus assistance, they might contemplate drafting opinions that engage amici more frequently in order to dispel an impression that the briefs are of little use.

[1] The total of 40 amicus briefs for 2014-15 is skewed by the 10 briefs filed in the unusual John Doe case decided at the end of the term—an unprecedently large number for a single case during the period under consideration.

[2] Once again it’s worth bearing in the mind the most unusual impact of the 10 amicus briefs in the single John Doe case of 2014-15.

[3] For example: May a public-housing tenant be evicted for engaging in drug-related criminal activity? May a person who challenges the revocation of probation on a withheld sentence be considered a “prisoner” for purposes of the Prison Litigation Reform Act’s filing requirements? Is the stamp law (requiring dealers to purchase tax stamps and place them on their illegal drugs) constitutional?

[4] Cases that resulted in per curiam decisions are included in all tables in this post. “Insurance cases” were identified by following the approach described in an earlier SCOWstats post, while the “Realtors Association” category includes all cases in which an amicus brief was filed by, or on behalf of, the Wisconsin Realtors Association or, in one instance, the Commercial Association of Realtors Wisconsin, Inc. The numbers in the latter category would be slightly higher if all cases were included that had anything to do with real estate, even cases with no amicus involvement by the Wisconsin Realtors Association (such as disputes involving a bank’s foreclosure effort, or contamination of property by a neighbor’s action).

[5] In other words, an opinion that states “neither the amicus nor the parties address this point” (with no further discussion focused on the amicus) would not be counted as engaging the amicus brief. If two or more amicus briefs in the same case are lumped together for a favorable (or unfavorable) mention, with no effort to distinguish the briefs from each other, they are counted as only one mention. If two or more amicus briefs are addressed separately in the same case, then they are counted separately. Sometimes, an amicus brief is engaged by more than one opinion (in which case, each opinion is counted separately), and (very rarely) a single opinion could cite a portion of an amicus brief favorably and another portion unfavorably. In the latter instance, both the favorable and the unfavorable mention are counted.

[6] There were 25 (rather than 24) favorable and unfavorable mentions because the majority opinion in one case (Marlowe v. IDS Property Casualty Insurance Company, 2011AP2067) cited a portion of the amicus contribution favorably and another portion unfavorably.

[7] The row for Boardman & Clark includes filings by Boardman, Suhr, Curry & Field and Lathrop & Clark. The Department of Justice’s row includes filings by the Attorney General’s Office and the Solicitor General’s Office. Laufenberg Law Group’s row includes filings by Laufenberg & Hoefle; Laufenberg, Jassack & Laufenberg; and Laufenberg, Stombaugh & Jassak.

[8] The briefs were engaged as follows. Boardman & Clark: three favorable mentions (one in a majority opinion and two in dissents). Department of Justice: five favorable mentions (three in majority opinions, one in a concurrence, and one in a dissent) and one unfavorable mention in a majority opinion. Gass Weber Mullins: one favorable mention in a majority opinion, and one unfavorable mention in a dissent. Godfrey & Kahn: a favorable and an unfavorable mention in the same majority opinion, and an unfavorable mention in another majority opinion. Henak Law Office: two favorable mentions (one in a majority opinion and one in a dissent) and one unfavorable mention in a majority opinion. State Public Defender’s Office: two favorable mentions in majority opinions, and two unfavorable mentions in majority opinions. UW Law School: one favorable mention in a concurrence, and one unfavorable mention in a majority opinion.

[9] AFSCME stands for American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees. One of the seven amicus briefs filed on behalf of Disability Rights of Wisconsin was filed in the Court of Appeals. Most of the amicus briefs in the “State of Wisconsin” row were filed on behalf of the Department of Justice, but there were also a handful filed on behalf of other departments.

Speak Your Mind