These tables are derived from information contained in 133 Wisconsin Supreme Court decisions that were turned up in a Lexis search for decisions filed between September 1, 1982, and August 31, 1983. The total of 133 decisions does not include rulings arising from (1) disciplinary proceedings against lawyers, and (2) various motions and petitions. Nor does the total include State ex rel. James Sykes v. Circuit Court for Milwaukee County, in which review was dismissed on grounds of mootness.

Also excluded are (1) In the Matter of Implementation of Felony Sentencing Guidelines, and (2) Report of Committee to Review the State Bar. These were actions without case numbers, briefing, or oral argument and that resulted in per curiam decisions.

The tables are available as a complete set and by individual topic in the subsets listed below.

Four-to-Three Decisions

Decisions Arranged by Vote Split

Frequency of Justices in the Majority

Distribution of Opinion Authorship

Frequency of Agreement Between Pairs of Justices

Average Time Between Oral Argument and Opinions Authored by Each Justice

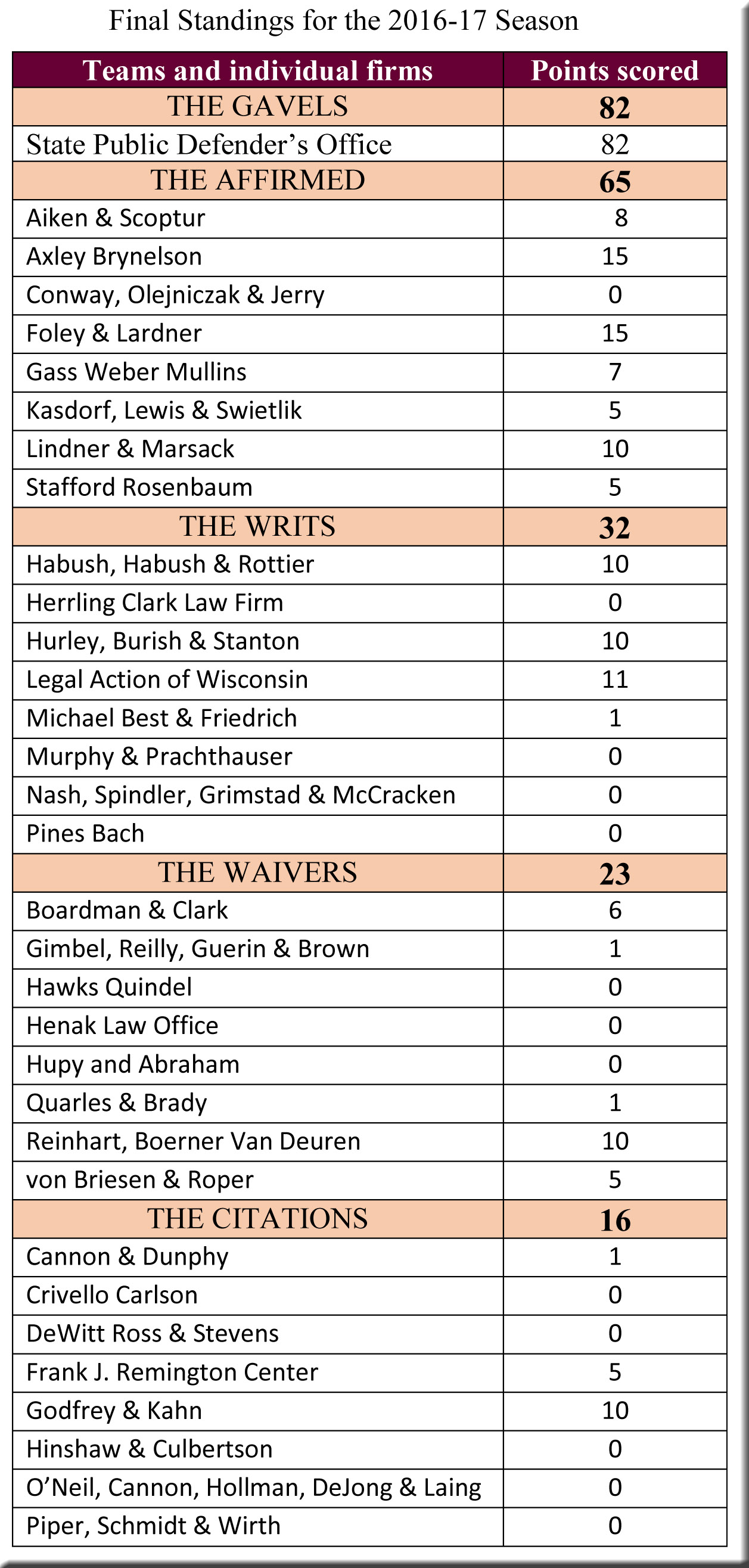

Number of Oral Arguments Presented by Individual Firms and Agencies