Previous posts[1] in this series have noted an increase in the number of original-action petitions accepted by the supreme court, and today we’ll see if this trend continued over the past three terms. Although most cases reach the justices in more leisurely fashion—passing through a circuit court and then the court of appeals before reaching the supreme court—the justices may accept a case as an original action, skipping the lower courts altogether. Such cases serve as an indication of the court’s priorities and sense of urgency—and, particularly for those who disagree with the decisions, evidence of “judicial activism.”

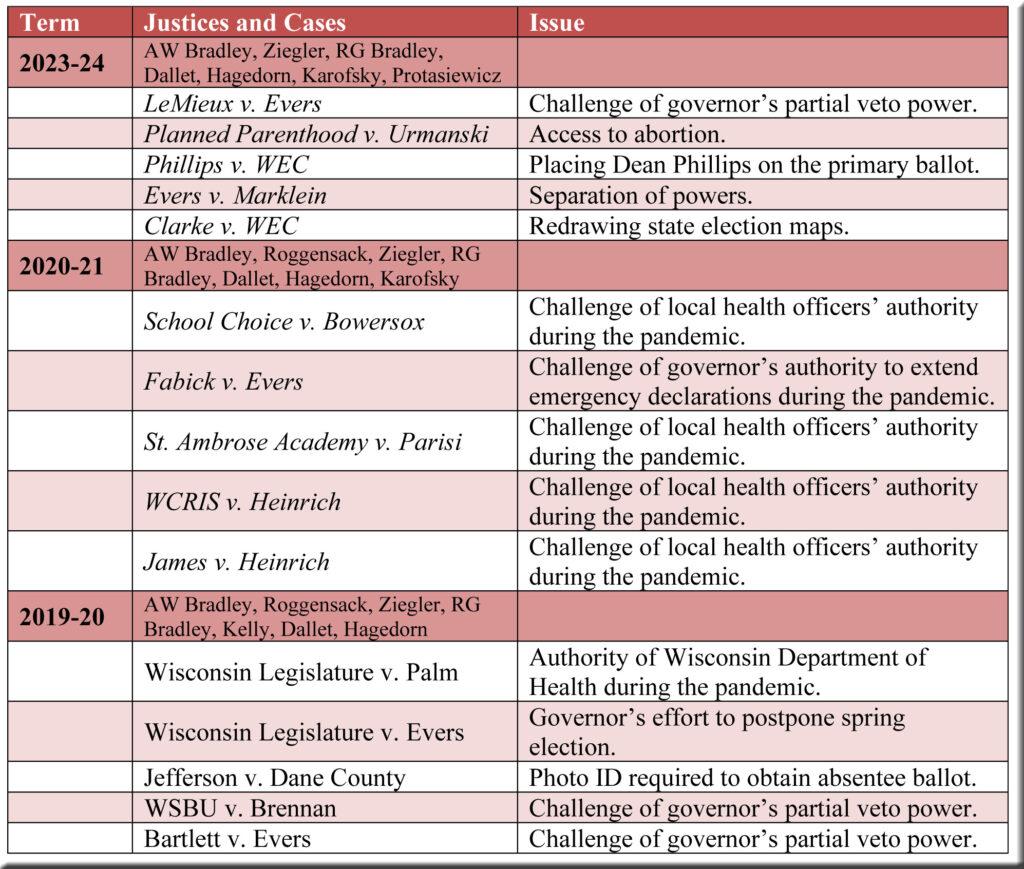

Last December, for instance, the court’s new liberal majority accepted Rebecca Clarke v. Wisconsin Elections Commissions as an original action and concurred with the petitioners’ argument that district maps for the state legislature were unconstitutional and must be redrawn. In dissent, Justice Ziegler protested that “[g]iving preferential treatment [as an original action] to a case that should have been denied, smacks of judicial activism on steroids.”

Back in 2020, with a conservative majority ascendant, the court sided with an original-action petition from the Wisconsin Legislature and quickly blocked certain COVID-mitigation measures that had been ordered by the secretary-designee of the Wisconsin Department of Health Services. Dissenting, Justice Dallet complained that the court’s remedy was more abrupt than even the legislature had requested. “This decision,” she asserted, “will undoubtedly go down as one of the most blatant examples of judicial activism in this court’s history.”[2]

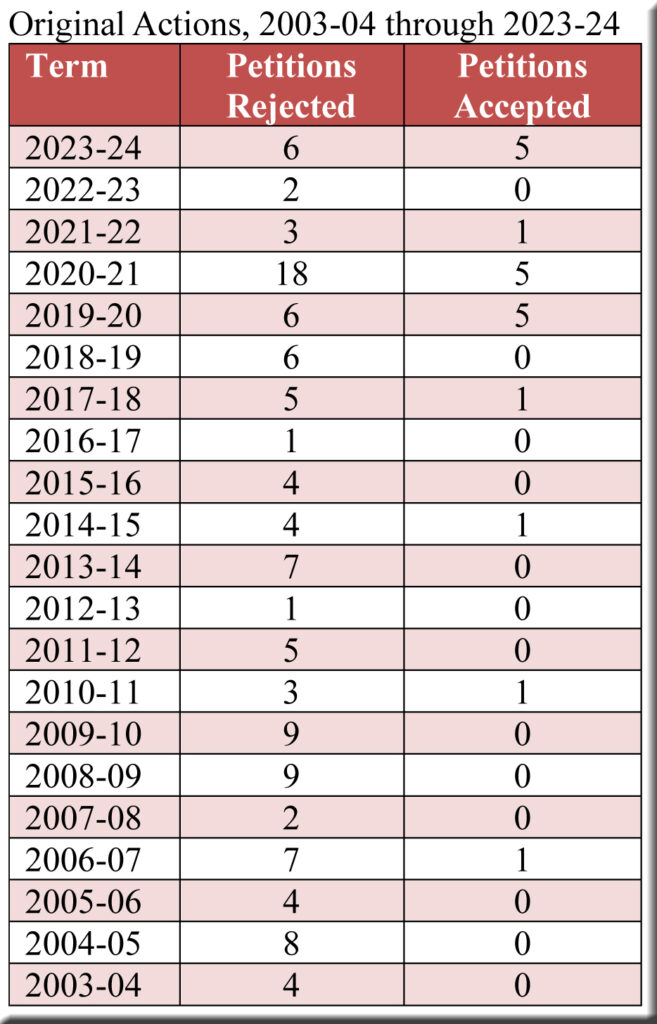

Number of original actions

Regardless of the court’s majority, most original actions accepted by the justices feature high-profile issues, and thus the volume of such cases merits attention when assessing the court’s activity over the years. The following table, covering 21 terms (from 2003-04 through 2023-24), displays the number of original-action petitions accepted and rejected. Cases are catalogued according to the “Decision Date” on the court’s website—that is, the date on which the court either denied the original-action petition or announced that it would hear the case.[3] This seems more appropriate than the “Submit Date”—the date when someone first submitted an original-action petition for the court’s consideration (which was the date that I had used in the preceding post).

The table shows an exceptionally high number of petitions granted in 2019-20 and 2020-21, ten in all,[4] which is where the previous post ended, leaving the question of whether this unprecedented development would continue. Over the next two terms, it did not, as only a single petition was accepted. But then, in 2023-24, the total jumped back to the same elevated level as in 2019-20 and 2020-21. Viewed in broader perspective, the table indicates that the court granted 16 original action petitions during the last five terms alone, compared to only four petitions over the preceding 16 terms combined. While it’s not certain yet that the court is moving toward routinely accepting original actions, the evidence is starting to point in that direction.

Politicized cases

The unusually large quantity of petitions granted recently suggests as well that the court is increasingly willing to arbitrate what have been called politicized disputes. Such cases lend themselves to arguments seeking expeditious rulings, and the justices—liberals and conservatives alike, when they have the upper hand—appear more inclined than ever to oblige. Consider the following table summarizing the issues in all the original actions accepted by the court in 2019-20, 2020-21, and 2023-24.

Conclusion

The original-action petitions granted in 2023-24 stand out more prominently than do such petitions accepted in any previous term. This impression stems not from the comparative importance of the issues over the years but from the fact that the court filed so few decisions of any sort—only 14—in 2023-24.[5] It will be interesting to see if original actions are similarly conspicuous in the court’s activity during the 2024-25 term, as the justices are likely to receive a cascade of petitions spawned by the contentious election this fall.

[1] “Original Actions and Judicial Activism” and “Original Actions and Judicial Activism: An Update for 2020-21”

[2] Wisconsin Legislature v. Andrea Palm.

[3] Terms run from September 1 through August 31 of the following year.

[4] The previous post had seven petitions in 2019-20 and three in 2020-21, rather than five for each term. As explained above, the difference between that post and this results from the fact that I am now categorizing cases according to the “Decision Date” rather than the “Submit Date.”

[5] By the end of the term, the court had yet to file decisions in two of the five cases in which original-action petitions had been accepted (Jeffery A. LeMieux v. Tony Evers and Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin v. Joel Urmanski).

Speak Your Mind