Coverage of this spring’s Wisconsin Supreme Court election has included assertions that a victory by Janet Protasiewicz would provide the court with a liberal majority for the first time since the tenure of Justice Louis Butler (2004-05 through 2007-08).[1] Such statements invite us to explore two questions: How “liberal” was the Butler court, and how might it compare in this regard with the court in 2023-24, following the replacement of Justice Patience Roggensack with Justice Protasiewicz?

“The Fourth Man”

Justice Butler had two liberal colleagues—Justices Shirley Abrahamson and Ann Walsh Bradley—and he voted in agreement with them in 61% of non-unanimous decisions during his four terms on the bench. To prevail, though, they needed at least one more vote, and Justice Patrick Crooks was the person who most often delivered it. Over the four Butler terms, Justice Crooks sided with the three liberals in 44% of non-unanimous decisions (Table 1)—considerably more often than the next closest “fourth man,” Justice David Prosser, who joined the three liberals in only 11% of non-unanimous decisions during this period.[2]

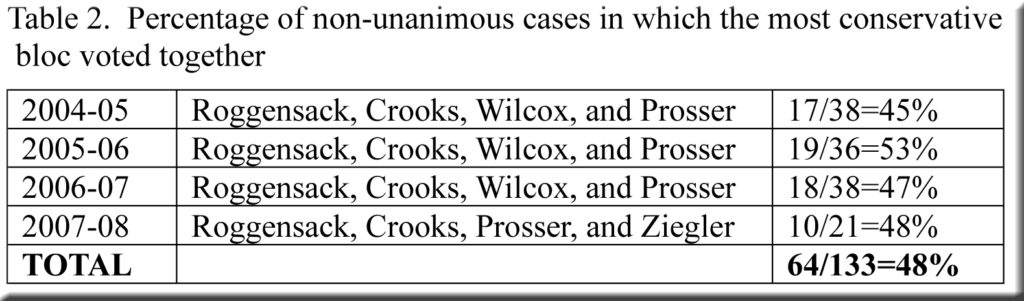

Meanwhile, the court also contained three conservatives—Justices Prosser, Patience Roggensack, and Jon Wilcox from 2004-05 through 2006-07, with Justice Annette Ziegler replacing the retiring Justice Wilcox for the 2007-08 term. They, too, required a fourth vote for a majority, and, just as with the liberals, their most frequent ally proved to be Justice Crooks. During the four terms in question, he joined the three conservatives in 48% of non-unanimous decisions, as detailed in Table 2.

As the tables demonstrate, the liberals + Justice Crooks, and the conservatives + Justice Crooks, each had an edge in two of the four terms, with the conservatives compiling a slight advantage overall, 48% to 44%. Therefore, it seems a stretch to describe the supreme court as “liberal” during Butler period.

Before Butler

Justice Abrahamson, the court’s archetypal liberal, joined the court in 1976, almost three decades before Justice Butler. This prompts the question of whether liberals ever enjoyed a stronger position on the court before 2004-05—and the answer is no. During Justice Abrahamson’s early years on the bench, she did not side with any three associates frequently enough to form a liberal quartet. Justices Abrahamson, Nathan Heffernan, Bruce Beilfuss, and Roland Day amounted to the nearest approximation, and they voted together in only 27% of non-unanimous decisions over the period 1976-77 through 1982-83.

The arrival of Justice William Bablitch in 1983 gave the court three members (Justices Abrahamson, Heffernan, and Bablitch) who could be regarded as at least fairly liberal. But even these three did not vote in unison routinely—for instance, only 46% of the time in non-unanimous decisions from 1990-91 through 1994-95. More important, they were not joined by a fourth justice to create anything close to a consistent liberal majority.

When Justice AW Bradley reached the court in 1995-96, she did so by replacing Justice Heffernan, and thus the court remained a vote short of a potential liberal majority. Her first three years coincided with Justice Janine Geske’s last three, and they, more than the other justices, voted with Justices Abrahamson and Bablitch. These four found themselves in agreement only 22% of the time in non-unanimous decisions during the three terms (1995-96 through 1997-98), and none of Justice Geske’s colleagues stepped in to raise this percentage more than a point or two after she retired. In the fall of 2003, Justice Roggensack replaced the retiring Justice Bablitch, leaving the liberals with only two votes on the eve of Justice Butler’s appointment the next year.

After Butler

Perhaps the Butler years came to appear liberal in retrospect because conservative dominance of the court grew so pronounced during the ensuing decade, beginning with Justice Michael Gableman’s electoral defeat of Justice Butler in 2008. When Justice Rebecca Bradley was appointed to succeed Justice Crooks (2015), followed by Justice Daniel Kelly’s replacement of Justice Prosser in 2016, the court attained its pinnacle of conservative ascendancy. Over the course of 2016-17 and 2017-18, at least four conservative justices voted in the majority of fully three-quarters (78%) of non-unanimous decisions.[3]

Through the next three terms, however, the conservative grip weakened. Although Justice Brian Hagedorn replaced the preeminent liberal, Justice Abrahamson, two new liberals—Justices Rebecca Dallet and Jill Karofsky—took seats previously held by a pair of the court’s staunchest conservatives (Justices Michael Gableman and Kelly) thereby yielding a liberal troika composed of Justices AW Bradley, Dallet, and Karofsky.

For anyone looking ahead to 2023-24, two points are vital to recognize. First, the new liberal threesome of Justices AW Bradley, Dallet, and Karofsky have voted together much more cohesively (82% of the time in non-unanimous decisions over the two most recent terms) than did the earlier liberal contingent of Justices Abrahamson, AW Bradley, and Butler (61%). Second, the enthusiastic endorsement of candidate Protasiewicz by Justices AW Bradley, Dallet, and Karofsky suggests that she is likely to provide a more dependable fourth vote for the liberals than did Justice Crooks during the Butler years. Consequently, the 2023-24 court could well display a liberal propensity unprecedented in the state’s modern era. To put it another way, while the liberal sway won’t quite match the conservatives’ hegemony in 2016-17 and 2017-18, it could be fairly close.

The Hagedorn Phenomenon

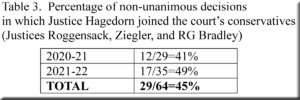

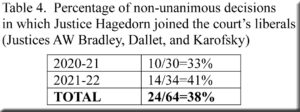

When Brian Hagedorn defeated Lisa Neubauer in 2019, winning the seat vacated by Justice Abrahamson, commentators portrayed the result as solidifying conservative control. It sent a “message to all of America that we’re ready to keep Wisconsin red as we turn our attention to mobilizing for 2020 and re-electing President Trump,” proclaimed Mark Jefferson, executive director of the Wisconsin Republican Party.[4] Since then, however, Justice Hagedorn has charted a course with some resemblance to that taken earlier by Justice Crooks—namely, leaning right, but by no means in lock step with the court’s doctrinaire conservatives, as shown in Tables 3 and 4.[5]

As Justice Hagedorn’s voting pattern crystallized, it elicited dismay (to use no stronger term) from conservatives. “Trump levels criticism against Brian Hagedorn to 88 million Twitter followers,” announced one headline, while another asserted that “Wisconsin conservatives feel ‘snookered’ by Supreme Court justice Brian Hagedorn.” More recently, Daniel Kelly himself described Justice Hagedorn as “supremely unreliable” and expressed regret that he had endorsed candidate Hagedorn back in 2019.[6]

Perhaps Justice Protasiewicz’s 25-year tenure as a prosecutor allows distraught conservatives to hope for something analogous to the Hagedorn phenomenon. That is, as her views emerge more clearly in the years to come, could she appear, if not “supremely unreliable” for the liberals, at least well short of a sure thing for them? Justice Hagedorn’s example makes it impossible to dismiss this outcome peremptorily, but for now it seems a slim reed for conservatives to grasp.

[1] See, for instance, Adam Edelman, Alexandra Marquez, and Bridget Bowman, “Liberals gain control of the Wisconsin state Supreme Court for the first time in 15 years,” NBC News, April 4, 2023; Nicole Gaudiano, “Why Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and other major Dems are going all out for a state Supreme Court race in Wisconsin,” Business Insider, March 24, 2023; and Shawn Johnson, “In a supreme court race like no other, Wisconsin’s political future is up for grabs,” National Public Radio, Weekend Edition Sunday, April 2, 2023.

[2] Here, and in other instances involving four justices, the percentages pertain to cases in which all four justices participated.

[3] The five conservatives were: Justices Roggensack, Ziegler, Gableman, RG Bradley, and Kelly.

[4] “Wisconsin Supreme Court race too close to call after 1.2 million votes,” CBS NEWS, April 3, 2019. See also Riley Vetterkind, “Brian Hagedorn’s likely Supreme Court win cements conservative dominance in state,” AP News, April 7, 2019.

[5] As with other tables in this post, the figures do not include a handful of cases in which at least one of the four justices did not participate.

[6] Molly Beck, “Trump levels criticism against Brian Hagedorn to 88 million Twitter followers,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, December 21, 2020; Scott Bauer, “Wisconsin conservatives feel ‘snookered’ by Supreme Court justice Brian Hagedorn,” Wisconsin State Journal, May 16, 2020; Patrick Marley, “Ex-Justice Daniel Kelly calls Brian Hagedorn ‘supremely unreliable’ as he considers pursuing a return to Wisconsin’s high court,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, April 28, 2022.

[…] Court watcher Alan Ball, a history professor at Marquette, has backed this up with numbers. In an analysis published a day after the election, he calculated that between 2004 and 2008, when Crooks was a […]