Recent data on petitions for review allow us to compare petitions submitted during the 2020-21 term with those featured in a post six years ago.[1] The previous post, which covered petitions in 2014-15, addressed criminal cases, and we will maintain that focus today in surveying the outcomes of petitions from the State, the Public Defender, private lawyers, and defendants themselves.

Results for 2020-21

Following the practice of the earlier post, we’ll cast our net to capture all cases with numbers bearing the CR suffix. Thinning[2] this haul leaves 287 petitions submitted between September 1, 2020, and August 31, 2021. Of these, 9% (25/287) were granted by the supreme court, but, as one would expect, the success rates varied dramatically among the different categories of filers. As shown in Table 1, petitions from the State (the Attorney General’s Office) were accepted 92% of the time—reflecting both the expertise of the Attorney General’s Office and the sympathies of the current justices. It’s worth noting as well that the State submitted very few petitions compared to the other litigants in Table 1, an indication of how routinely the State prevails in the lower courts.

Table 1 also confirms findings from previous years that petitions submitted by defendants themselves (generally inmates) have essentially no chance of acceptance. Public defenders (8%) fared better than private lawyers (5%), but both encountered tough sledding in their efforts to persuade the justices to hear their appeals.[3]

2020-21 and 2014-15

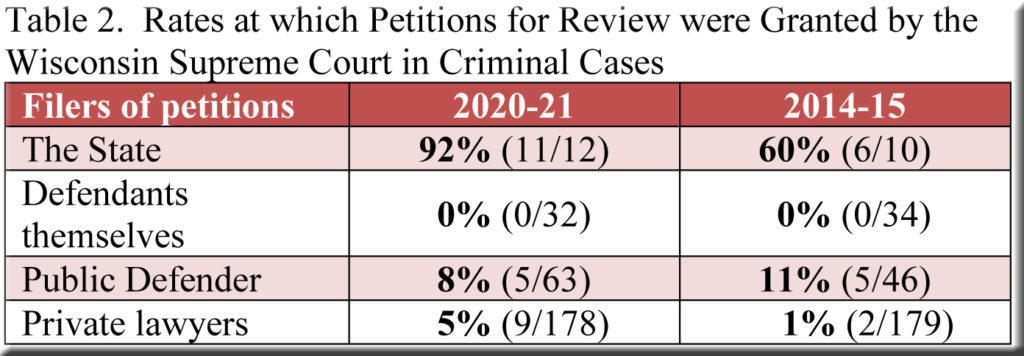

A number of changes catch the eye in measuring the 2020-21outcomes against those from 2014-15, when the court consisted of Justices Abrahamson, Bradley, Crooks, Prosser, Roggensack, Ziegler, and Gableman. For one thing, while the justices still accepted more than half of the State’s petitions in 2014-15, they regarded them with considerably more skepticism—granting “only” 60% of these petitions that term, compared to 92% in 2020-21 (Table 2).

Meanwhile, although the court accepted the same number of petitions, five, from the Public Defender’s Office in 2020-21 as it did in 2014-15, public defenders had to submit far more petitions in order to reach this figure in 2020-21—hence, their success rate fell from 11% to 8%. In contrast, private lawyers did much better in 2020-21 than in 2014-15. Their success rate did not equal that of the public defenders, but it climbed impressively from 1% to 5%.

Epilogue

It bears mention that convincing the justices to grant a petition does not guarantee that they will proceed to issue a ruling desired by the filer. The supreme court has yet to decide some of the 2020-21 cases,[4] but the results to date have not been encouraging for public defenders and private lawyers, who are still without a favorable outcome (0/7) in cases where their petitions were granted. This differs sharply from the State’s experience. After accepting petitions filed by the Attorney General’s Office in 2020-21, the court has so far ruled in favor of the State 70% of the time.[5]

[1] The raw data for this post was provided by Supreme Court Commissioner Nancy Kopp, and I am most grateful for her assistance.

[2] Frequently, two or more cases were consolidated as one—but were listed on separate lines in the raw data. I identified these instances and removed the “duplicate” lines.

I am omitting a total of four cases where (1) the court announced that it would take no action on a petition; (2) a petition was withdrawn; and (3) two petitions were held in abeyance pending the disposition of another case.

Four cases with CRLV suffixes are included, but cases with CRNM suffixes are not. Nor are “No-Merit” petitions for review.

In State v. Robert Daris Spencer the court granted both a petition for review (from a private lawyer) and a cross-petition for review (from the State). I have counted them both.

In two cases the court summarily dismissed a petition and then, a couple months later, denied another petition. I counted each petition in both cases.

[3] The “All filers” category also includes a case in which the petition was filed by the Frank J. Remington Center at the University of Wisconsin Law School, and a case in which the petition was filed by Joseph Kearney, Dean of the Marquette University Law School. The supreme court denied both petitions.

[4] State v. Nhia Lee (dismissed as improvidently granted) and State v. Joseph G. Green (affirmed in part, reversed in part) are omitted here, as are six other cases that will not be decided until next term.

[5] More specifically, the court’s rulings have favored the State in seven out of ten such cases so far. The total of ten includes State v. Manuel Garcia, where the ultimate result proved unfavorable for the State, because the supreme court affirmed the court of appeals by means of a deadlocked (3-3) per curiam decision.

Speak Your Mind