A reader, who prefers anonymity, inquired recently about reversal rates for court of appeals judges. His interest extended beyond summary figures from the four court of appeals districts, he explained, for he was curious to learn how frequently the supreme court affirmed or reversed individual judges. While the court’s website does provide some information for the districts, I am not aware of reports on how the supreme court appraised the votes of each judge separately. So, let’s find out.

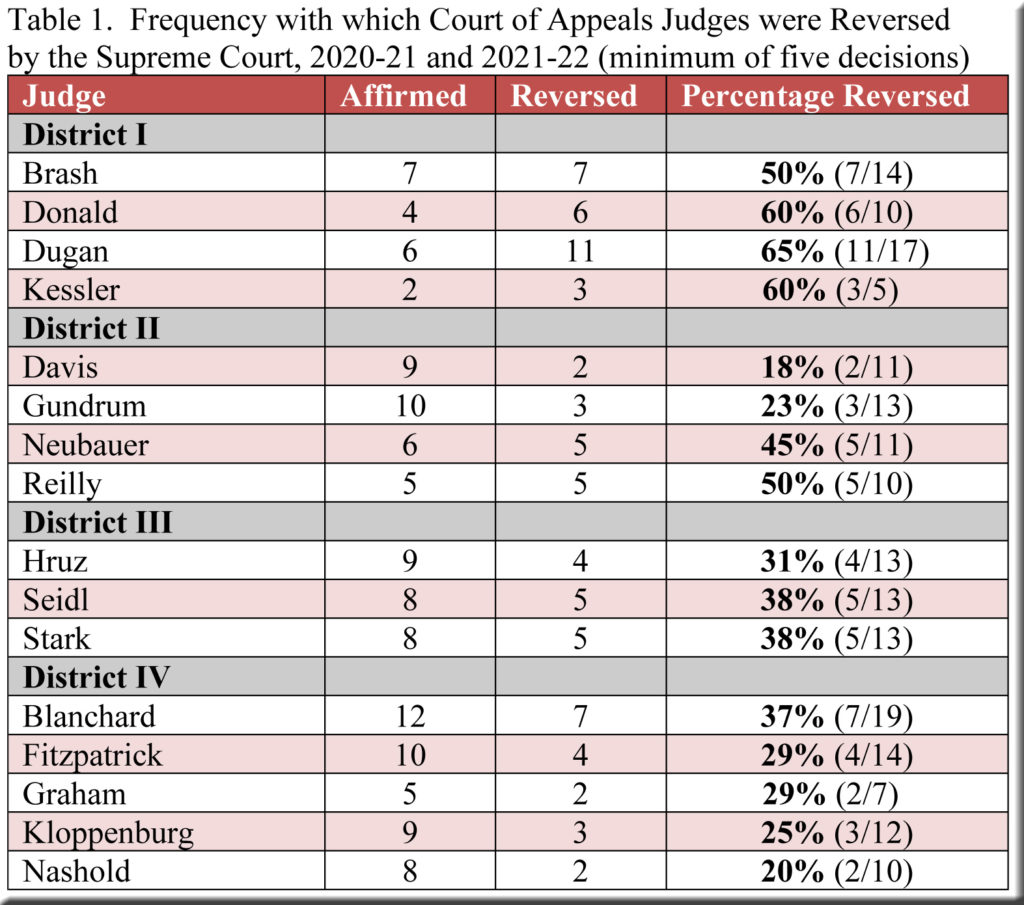

Our study covers 70 decisions filed during the last two terms by the supreme court, reviewing decisions from the court of appeals.[1] In order to appear in the following tables, a court of appeals judge had to participate in at least five of these 70 cases—a standard that 16 judges met.[2] Nearly all of the cases (65) had three-judge court of appeals panels (with the remaining five decided by a single judge), and all but four of the three-judge decisions were unanimous.[3] No concurrences surfaced from the three-judge panels to qualify or otherwise elaborate on their mandates. To be clear, if the supreme court affirmed (or reversed) a decision by a unanimous three-judge panel, all three judges are counted as affirmed (or reversed)—not just the judge who authored the opinion.

Table 1 shows that the highest reversal rates occurred among the judges in District I—60% or more for Judges Dugan, Donald, and former Judge Kessler. At the other end of the spectrum, we find former Judge Davis of District II, whose votes were rejected only 18% of the time by the justices in Madison.[4]

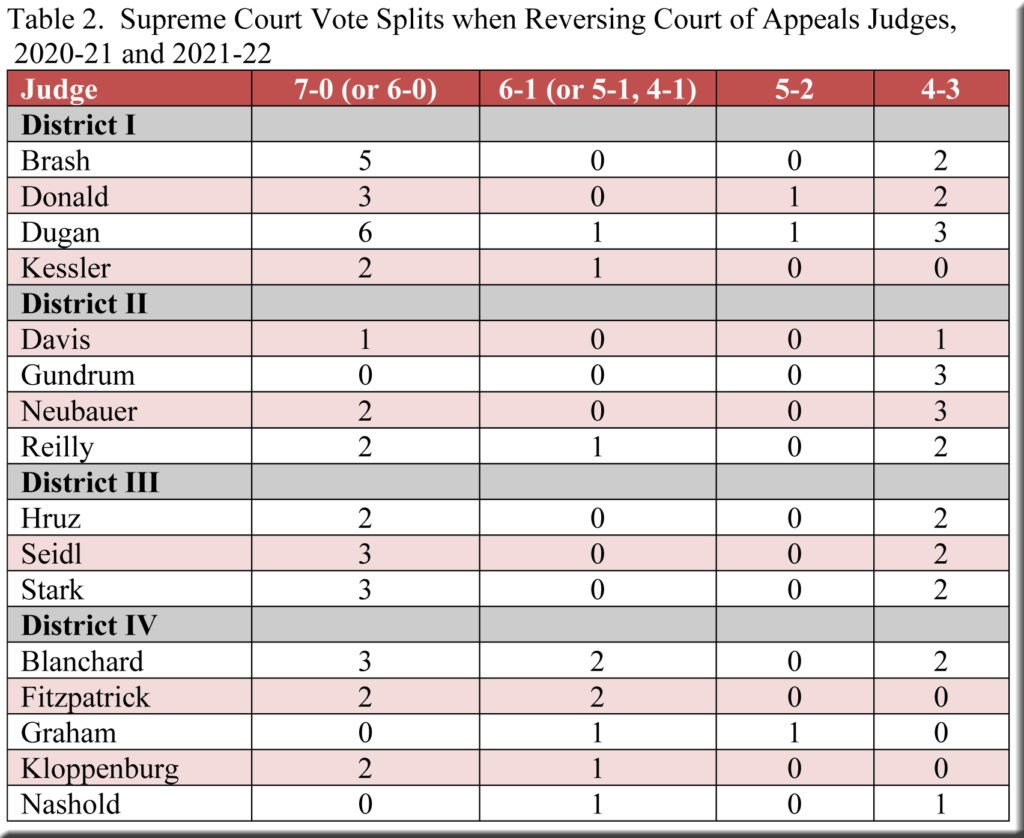

Table 2 narrows our focus to only those cases where court of appeals judges were reversed, and it tallies the vote splits in the supreme court for each of these decisions. Thus, for example, the table indicates that in all three cases where the justices rejected Judge Gundrum’s votes, they did so by a 4-3 margin. At the other extreme, Judge Brash sustained the highest percentage of unanimous reversals—five out of seven, or 71%.[5]

Opinions will vary as to whether frequent reversals should be regarded as cause for concern or praise—depending on one’s view of the supreme court in general and the issues in specific cases. In any event, however, these tables offer food for thought, as differences among the judges are certainly pronounced.

[1] Excluded are cases that reached the supreme court as original actions or on certification or bypass. I have also omitted County of Dane v. PSC of Wisconsin—an unusual case where the court of appeals was not centrally involved, and the supreme court’s reversal pertained to various decisions made by the circuit court. Excluded, too, are three cases in which court of appeals rulings were affirmed in part and reversed in part by the supreme court: State v. Alan M. Johnson; State v. Robert Daris Spencer; and Mohns Inc. v. BMO Harris Bank National Association.

Finally, there are a handful of “gray-area” cases where views might reasonably differ as to whether they should be included. Five received affirmed-as-modified rulings by the supreme court, while a sixth (Loren Imhoff Homebuilder, Inc. v. Lisa Taylor and Luis Cuevas) was reversed in part and deadlocked in part (because only six justices participated). I have omitted Loren Imhoff and one of the affirmed-as-modified cases (State v. Scott W. Forrett) but included the other four affirmed-as-modified cases (Danelle Duncan v. Asset Recovery Specialists, Inc.; State v. Mark D. Jensen; Timothy Zignego v. Wisconsin Elections Commission; and State v. X.S.).

[2] The following judges participated in fewer than five decisions reviewed by the supreme court and are thus not included in the tables: Brennan, Gill, Grogan, Hagedorn, Kornblum, Lundsten, and White.

[3] On a few occasions, one or more judges from one district participated in a decision labelled as issued by the court in a different district. This is irrelevant for our purposes, as the figures presented here are compiled for individual judges, not the four districts among which the judges are divided.

[4] The table accounts for (1) Judge Fitzpatrick’s dissent in State v. Angel Mercado, where the supreme court shared his view and reversed the court of appeals; (2) Judge Reilly’s dissents in Nudo Holdings, LLC v. Board of Review for the City of Kenosha and Gail Moreschi v. Village of Williams Bay and Town of Linn ETZ Zoning Board of Appeals, where the supreme court rejected his arguments and affirmed the court of appeals; and (3) Judge Hruz’s dissent in State v. Adam W. Vice, where the supreme court shared his view and reversed the court of appeals.

[5] The figures in Table 2 account for dissents by Judges Fitzpatrick, Reilly, and Hruz, as explained in a previous footnote.

Speak Your Mind