With the final substantive decision of the term now published, we can begin our annual statistical assessment of the justices’ labors. Today we’ll focus on the number of decisions, the issue of polarization, and Justice Hagedorn’s sway—and then take up a variety of other topics in the next week or two.

Number of decisions filed

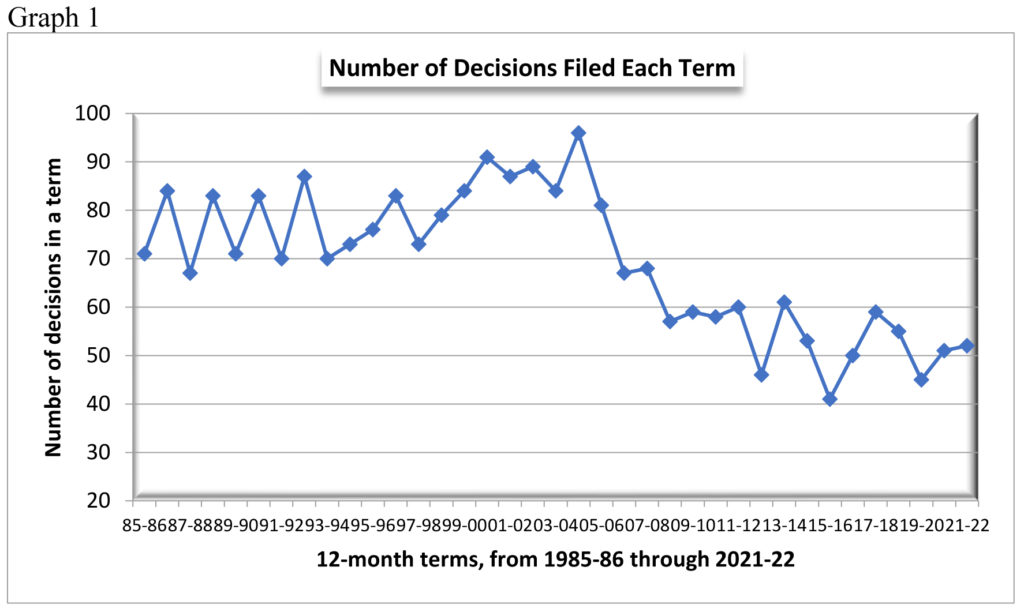

The court’s yield of 52 decisions in 2021-22 is nearly identical to the total of 51 in 2020-21,[1] and exactly the same as the average for the preceding decade—though well below the average of 75 during the decade before that (2001-02 through 2010-11), as evident in Graph 1.

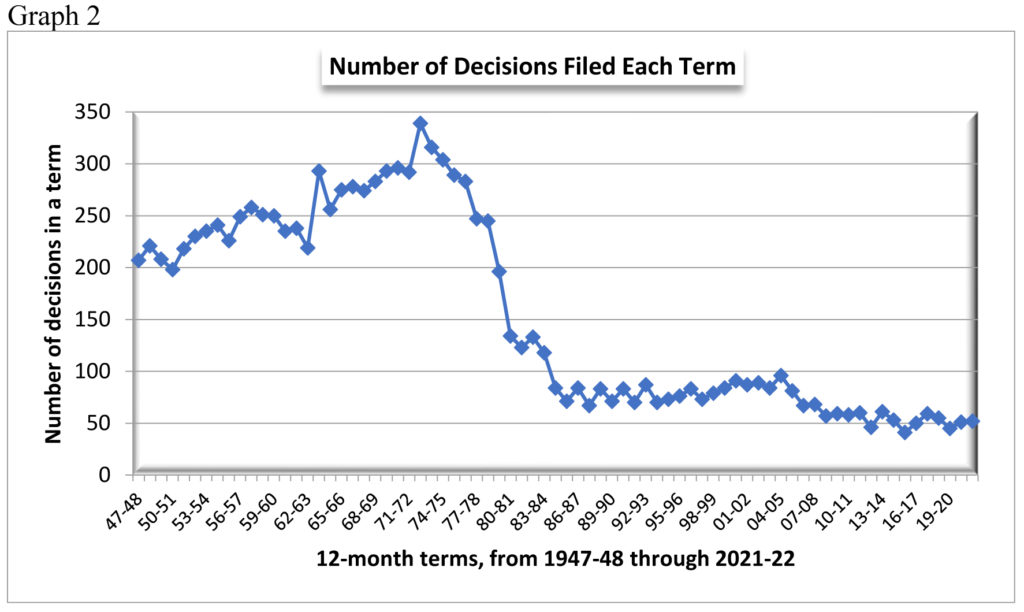

Although the average of 75 decisions per term towers above the court’s output in recent years, it is dwarfed by the numbers filed in the 1970s—often in the neighborhood of 300 decisions per term—prior to the formation of the court of appeals. Extending our gaze further back, we see (Graph 2) that the average declined to approximately 200 decisions per term by the late 1940s, the current limit of our data. As we continue to peer deeper into the past, it will be interesting to discover if such events as World War II and the Depression coincide with significant changes in the graph.

Polarization

We’ve observed that a court becomes polarized when “an unyielding bloc of justices almost always votes together, and almost always in opposition to another, similarly resolute, set of justices.” Recently, the two “unyielding blocs” have taken the form of three “liberals” (Justices A.W. Bradley, Dallet and Karofsky) and three “conservatives” (Justices Roggensack, Ziegler, and R.G. Bradley)—with both blocs demonstrating tenacious cohesion. To put numbers on this tenacity, the three liberals voted together 88% of the time, and the three conservatives kept in step even more frequently, in 92% of the term’s cases.[2]

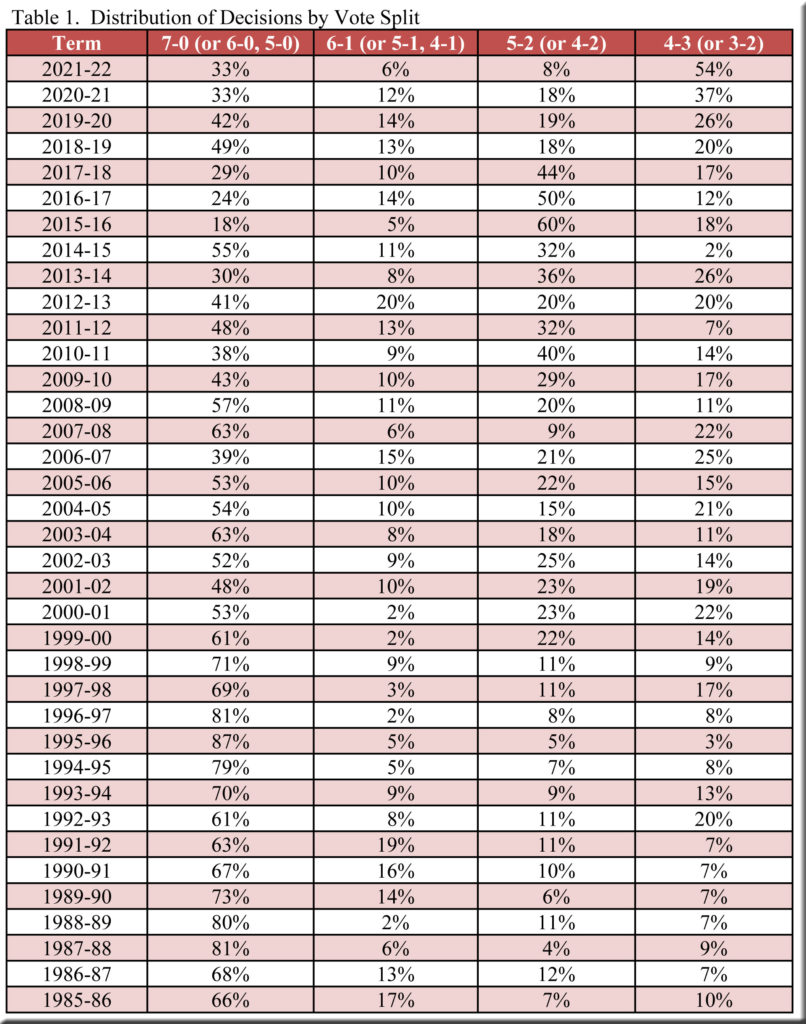

With at least three justices nearly always locking arms, this term’s voting pattern acquired some unusual aspects. For one thing, cases decided by 6-1 or 5-2 margins became rare, representing only 14% of the 52 votes taken, as shown in Table 1.[3] Of course, this by itself does not necessarily signify polarization, as a court in which most votes were unanimous would also have few 6-1 or 5-2 decisions (see, for example, the entries for 1995-96 in Table 1).

However, in 2021-22 it was not the portion of unanimous decisions but the share of 4-3 decisions that ballooned. Accounting for 54% of all decisions (Table 1), this percentage of 4-3 outcomes is unprecedented in the three-quarters of a century surveyed by SCOWstats and is arguably the most striking feature of the 2021-22 term.

The origin of this “4-3 Surge” may be traced to Justice Jill Karofsky’s arrival on the court for the 2020-21 term, after her electoral defeat of conservative Justice Daniel Kelly. This made possible the “liberal bloc” of three justices noted above, and consequently the share of 4-3 votes jumped to 37% that term—dramatic at the time, but just a warmup for the leap to 54% in 2021-22.

The importance of Justice Hagedorn

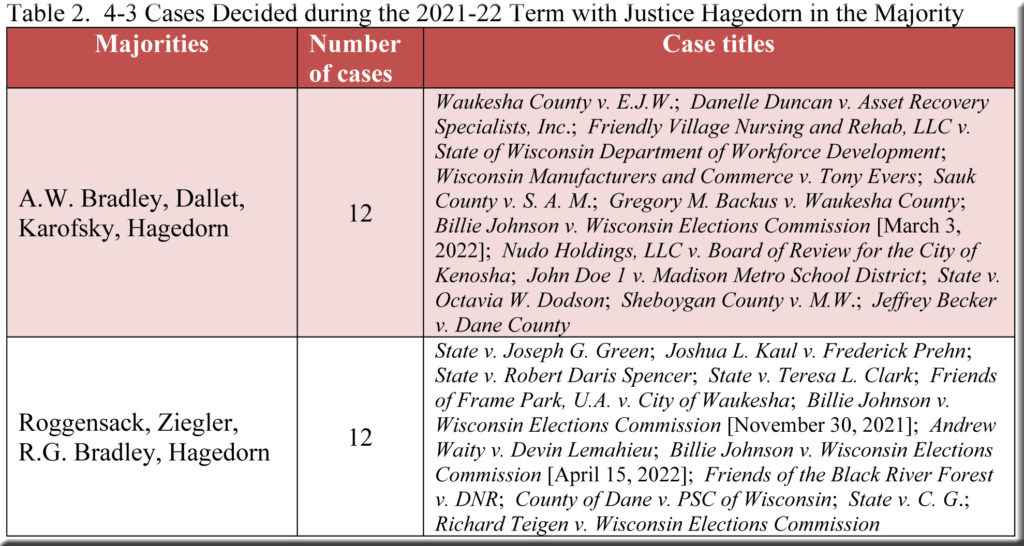

As the court hardened into polarized three-justice blocs, Justice Brian Hagedorn became ever more vital. In contentious cases it was extremely rare for a member of either bloc to “defect” to the other, and therefore most 4-3 outcomes depended on his vote. Previous posts have remarked on Justice Hagedorn’s increasingly pivotal role among the justices, and the court’s concluding flurry of 4-3 decisions in July highlighted the crucial nature of his support.

Specifically, nine of the court’s last 11 decisions were decided by 4-3 votes, and Justice Hagedorn appeared in eight (89%) of these nine majorities. For the term as a whole, he joined the majority in 86% of cases (24/28) with 4-3 decisions—a percentage that no other justice approached, as only Justices R.G. Bradley and Karofsky (both 57%, 16/28) even topped 50%.

Justice Hagedorn (formerly legal counsel for Republican Governor Scott Walker) began his tenure with a reputation as a conservative, and he has indeed teamed with the conservative bloc (Justices Roggensack, Ziegler, and R.G. Bradley) in a number of prominent 4-3 votes this year—including Billie Johnson v. Wisconsin Elections Commission (adopting election-district maps favored by Republicans), Joshua L. Kaul v. Frederick Prehn (holding that a Walker appointee on the Wisconsin Board of Natural Resources may not be removed after his term expires until his replacement has been confirmed by the senate, even if the Republican-controlled senate chooses not to act), and Richard Teigen v. Wisconsin Elections Commission (banning most absentee-ballot drop boxes).[4] Thus one might reasonably anticipate that, with the court divided into conservative and liberal blocs, Justice Hagedorn would side more often than not with the conservatives.

Yet, he has not done so, and this is surely the biggest surprise regarding the court over the past two years. While Justice Hagedorn has routinely cast the deciding vote in 4-3 decisions, fully half of these votes found him tipping the balance to the liberal bloc this term, as detailed in Table 2.[5]

Conclusion

Both of these developments—the torrent of 4-3 decisions and Justice Hagedorn’s role—have been remarkable, and we may see more of the same in 2022-23, given that the court’s composition is not expected to change.

[1] I am not going to include deadlocked (3-3) per curiam decisions in these totals, and I have adjusted the figures accordingly for all of the years in Graphs 1 and 2. (There were two 3-3 decisions in 2021-22 and one in 2020-21.)

[2] The percentages are calculated for cases in which all three justices participated: 44/50 for the liberals and 48/52 for the conservatives. No other trio of justices could match this level of agreement—for instance, 69% for Justices Roggensack, Ziegler and Hagedorn, and 63% for Justices A.W. Bradley, Dallet, and Hagedorn.

[3] The 6-1 category also includes a small number of 5-1 and 4-1 votes, and the 5-2 category includes a few 4-2 votes. As a result of rounding, the percentages do not always add up to 100.

[4] Billie Johnson reached the supreme court three times in 2021-22. The reference here is to the final decision, filed on April 15.

[5] The four 4-3 cases where Justice Hagedorn dissented in 2021-22 are: State v. Scott W. Forrett; State v. Chrystul D. Kizer; State v. X.S.; and Cree, Inc. v. LIRC. In the first two cases, Justices A.W. Bradley, R.G. Bradley, Dallet, and Karofsky formed the majority; in the last two cases the four majority votes came from Justices Roggensack, Ziegler, R.G. Bradley, and Karofsky.

[…] Alan Ball, The Supreme Court’s 2021-22 Term: Some Initial Impressions, SCOWstats (July 13, […]