Now that the supreme court has filed its last substantive decision of the 2019-20 term, we can begin our customary series of posts on various aspects of the justices’ work over the past 12 months. Along the way, we’ll encounter some surprises.

Number of decisions filed

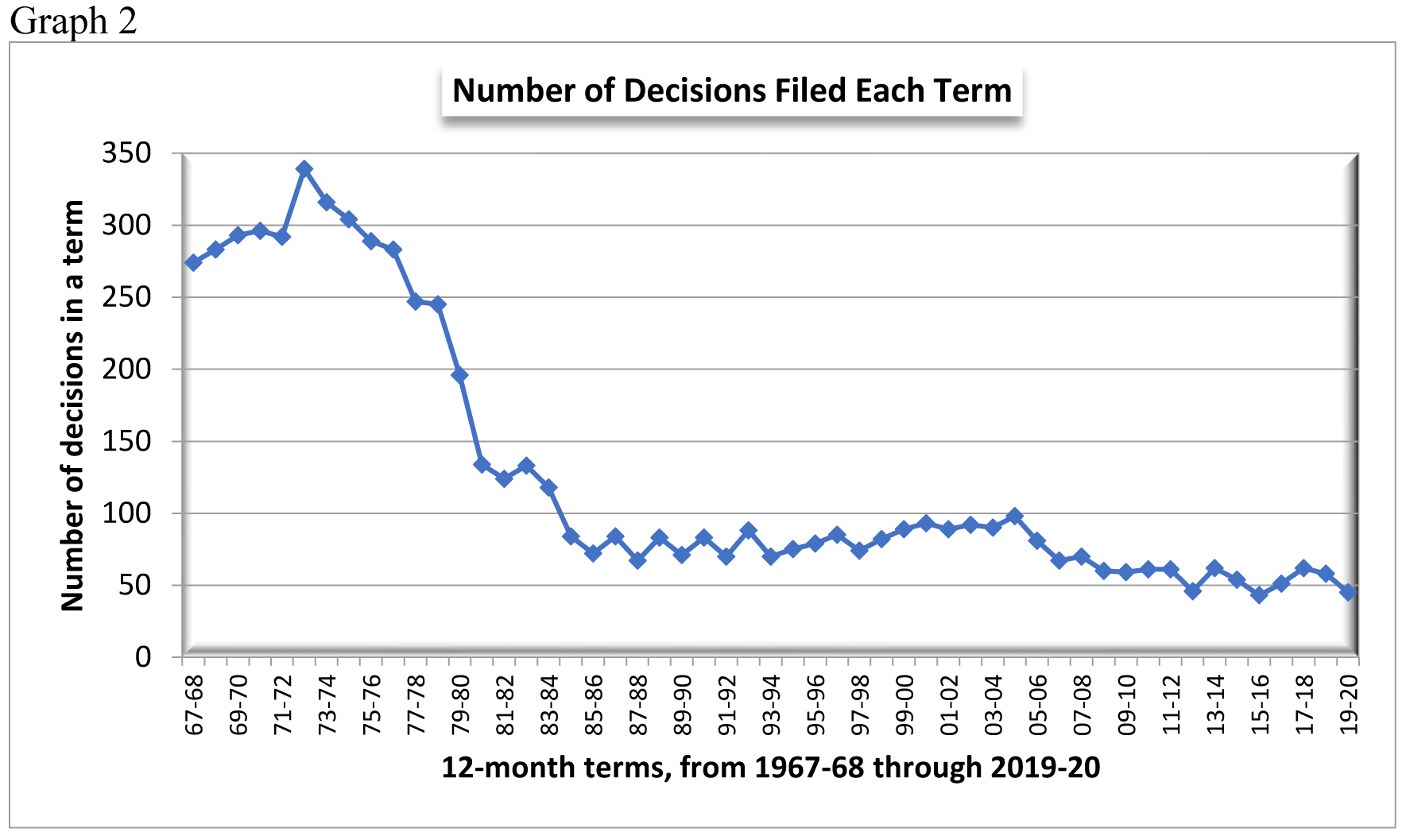

These summaries normally start by comparing the term’s volume of decisions with the totals filed during other terms, both recent and remote. This year the change was dramatic. From 58 decisions in 2018-19 (and 62 in 2017-18), the total plunged to 45 in 2019-20. This approached the modern-day low of 43, as shown in Graph 1.

Although complications associated with the pandemic may have played a part, by March the court’s calendar had already made it clear that the number of decisions would be unusually low. One might expect a sharp rebound in 2020-21, as the court has never filed fewer than 50 decisions two terms in a row during the modern era. But, in these coronavirus days, it’s hard to muster confidence for predictions of almost anything.

Meanwhile, since our last summary, SCOWstats has extended its coverage several years farther into the past, back to 1967-68. The result is displayed in Graph 2, which highlights yet again the justices’ massive output before the new court of appeals came online at the end of the 1970s, as well as the fact that only 15 years ago the justices filed 98 decisions—some of them authored by two of the court’s current members.

Polarization

Turning to the topic of polarization, a fixture among court watchers, certain findings will not astonish. For instance, the court’s two liberals (Justices A.W. Bradley and Dallet) took the same side 100% of the time,[1] and the court’s two most established conservatives (Justices Roggensack and Ziegler) joined each other in 93% of their votes.[2] However, these four justices voted together six times in non-unanimous decisions,[3] an agreement rate of 24% (6/25)—well above the agreement rate in non-unanimous decisions for Justices Abrahamson, A.W. Bradley, Roggensack and Ziegler in 2017-18 (12%) and 2016-17 (8%).[4]

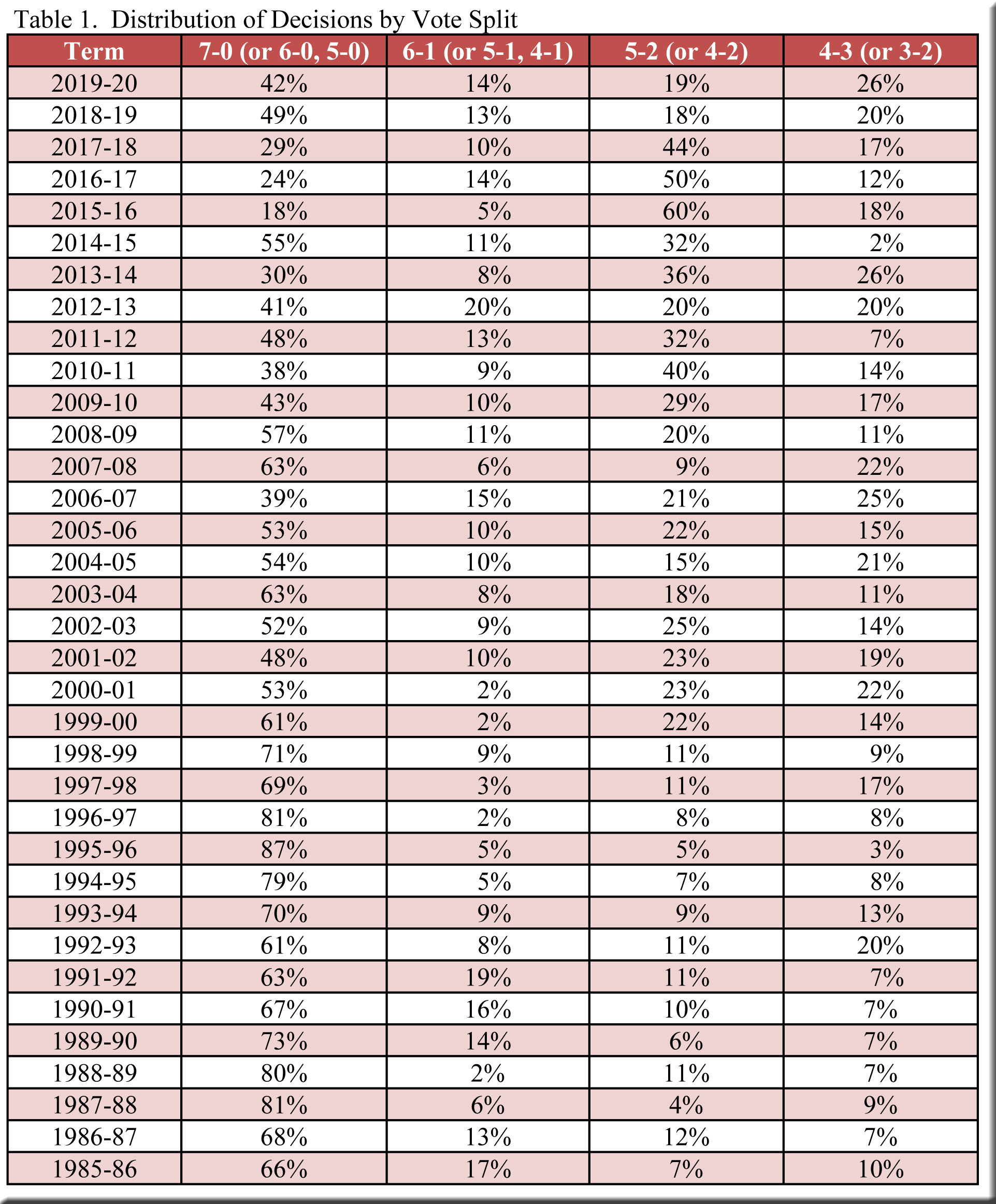

Figures for 5-2 (and 4-2) decisions—Table 1—also suggest moderated polarization. The pattern in recent years featured a very large percentage of 5-2 decisions, with Justices Abrahamson and A.W. Bradley by far the most frequent pair of dissenters. Nothing underscored the court’s schism more vividly than the isolation of these two justices.

As last year’s post noted, Justice Abrahamson’s deteriorating health and diminished participation made it difficult to interpret the abrupt drop in the percentage of 5-2 decisions that term. But the percentage remained low in 2019-20, and, just as striking, the court’s two liberals were the dissenters less regularly than before.

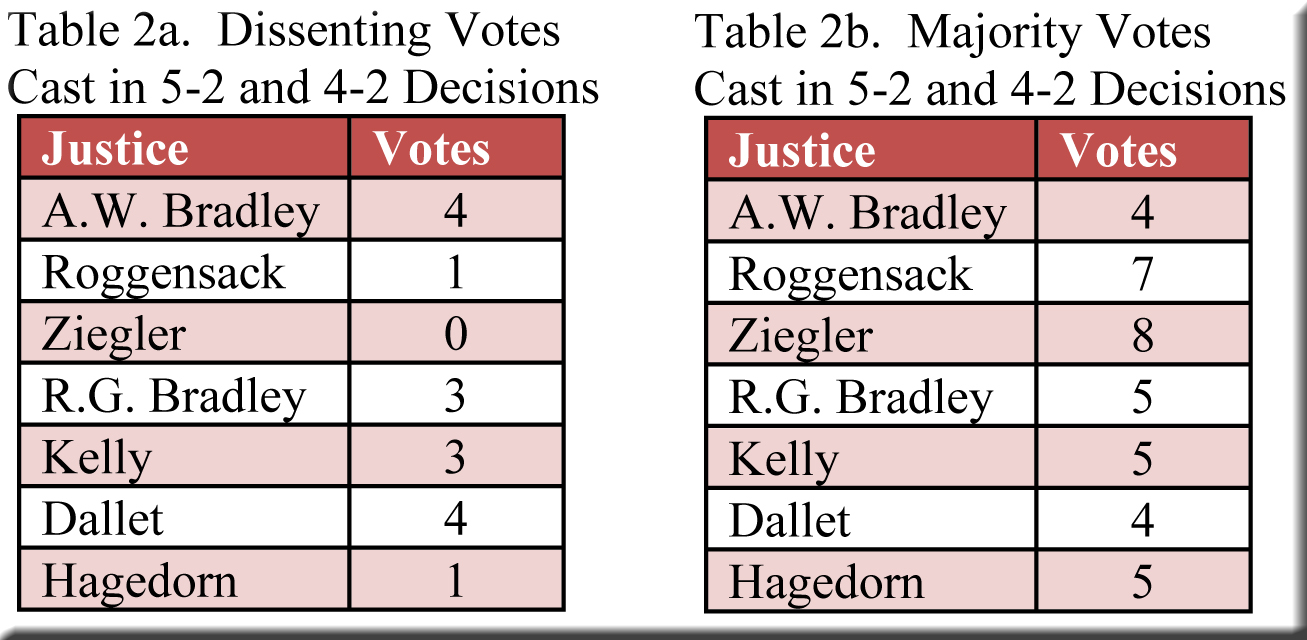

As detailed in Tables 2a and 2b, Justices A.W. Bradley and Dallet did dissent more often in 5-2 decisions than any other justice—but not by a great deal. They dissented in 4 of the 8 votes, while Justices R.G. Bradley and Kelly did so in 3 of the 8. Compare this to 2017-18, when Justices Abrahamson and A.W. Bradley cast the two dissenting votes in 73% of such cases—and 84% in 2016-17.

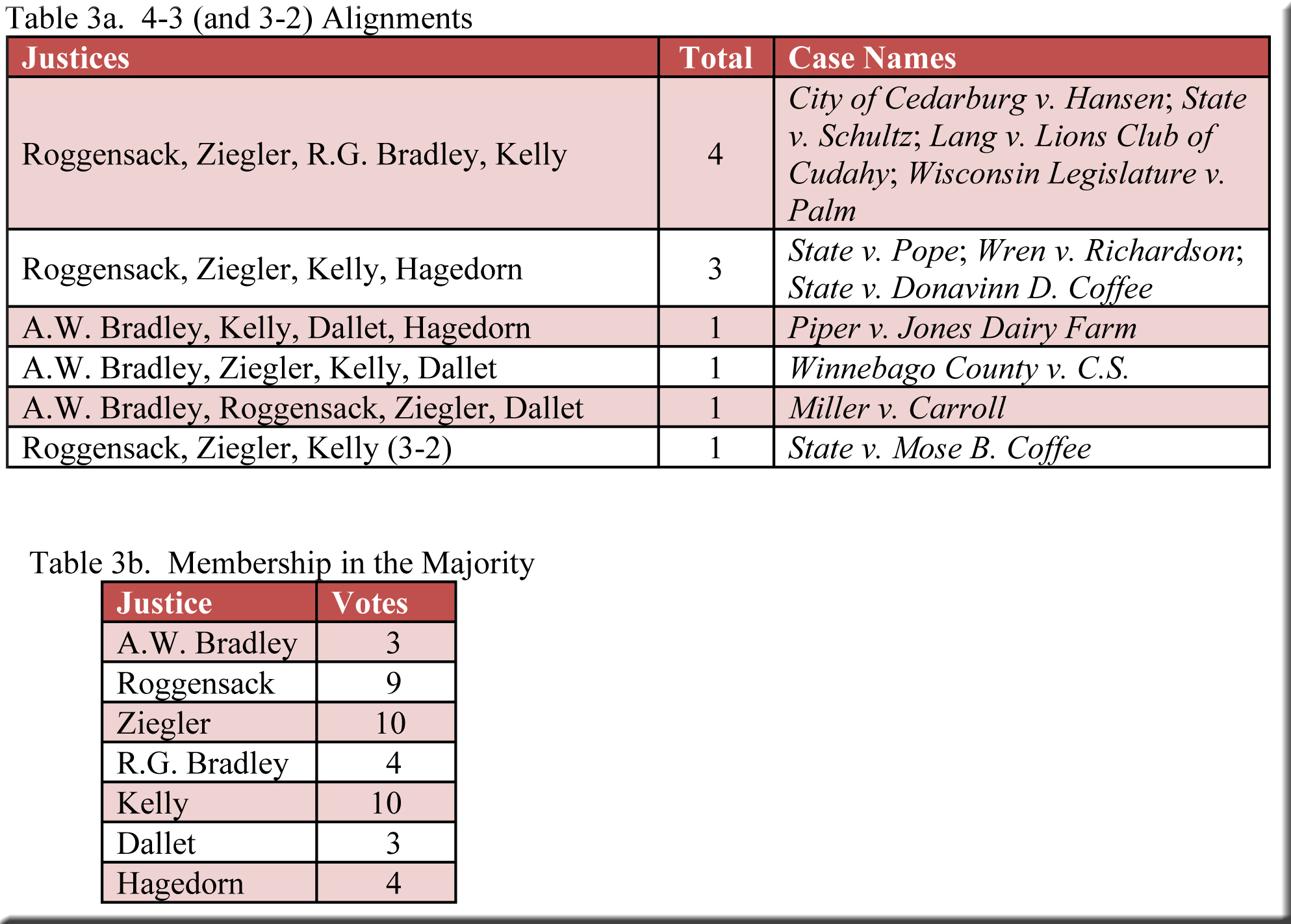

None of this should obscure the fact that the court remained resolutely conservative—a decisive reality in eight of the eleven 4-3 (and 3-2) decisions. As evident in Tables 3a and 3b, the court’s three most predictable conservatives appeared in the majority almost every time. However, as in 5-2 decisions, Justices A.W. Bradley and Dallet figured in the 4-3 majorities nearly as often as Justices R.G. Bradley and Hagedorn. To be sure, the conservatives’ control of the court could absorb the dissent of either Justice R.G. Bradley or Justice Hagedorn and still prevail by at least a 4-3 margin, but this luxury may evaporate when Justice Karofsky replaces Justice Kelly.

Conclusion

To what extent the foregoing will change with the arrival of Justice Karofsky is an intriguing question for the upcoming term. Few surprises are likely from Justices A.W. Bradley, Dallet, Roggensack, and Ziegler, so, apart from Justice Karofsky herself, much depends on Justices R.G. Bradley and Hagedorn. Although both of them inhabit the conservative domain, they have been considerably less inclined to side with each other than have the Roggensack-Ziegler pair—and, indeed, Justice Hagedorn has voted with Justices A.W. Bradley and Dallet slightly more often than he has with Justice R.G. Bradley.[5] I had not anticipated this and will be curious to see if anything of the sort recurs after Justice Karofsky takes her seat on bench.[6]

[1] In cases where both participated.

[2] In a couple days, the next post in this series will provide the rates of agreement among all possible pairs of justices.

[3] In some instances, by means of concurring opinions. Service Employees International Union (SEIU), Local 1 v. Robin Vos and Nancy Bartlett v. Tony Evers defy ready categorization and are omitted from these calculations.

[4] I did not calculate a figure for 2018-19, because Justice Abrahamson’s declining health greatly reduced her participation.

[5] As noted above, the next post in this series—due in a couple days—will provide details on the rates of agreement among the justices.

[6] For speculation on Justice Karofsky’s possible impact on “conservative discipline” among the justices, see “Jill Karofsky and ‘Bloc Cohesion’ at the Wisconsin Supreme Court.”

Speak Your Mind