Many luminaries in the legal profession have remarked to the effect that “An activist court is one whose decisions you don’t like.”[1] Scholarly attempts to define judicial activism suggest a number of other factors to consider, and today I’d like to offer readers an opportunity to contemplate whether the supreme court’s frequent embrace of “original actions” should be included in the list of criteria.

Normally, a case reaches the supreme court only after starting in a circuit court and then traveling through the court of appeals. However, the supreme court has the authority to accept a case at the outset as an original action, bypassing the lower courts altogether. According to the State Bar’s Appellate Practice and Procedure in Wisconsin, original actions are intended for “matters of great public importance,” especially “when time is of the essence.”[2]

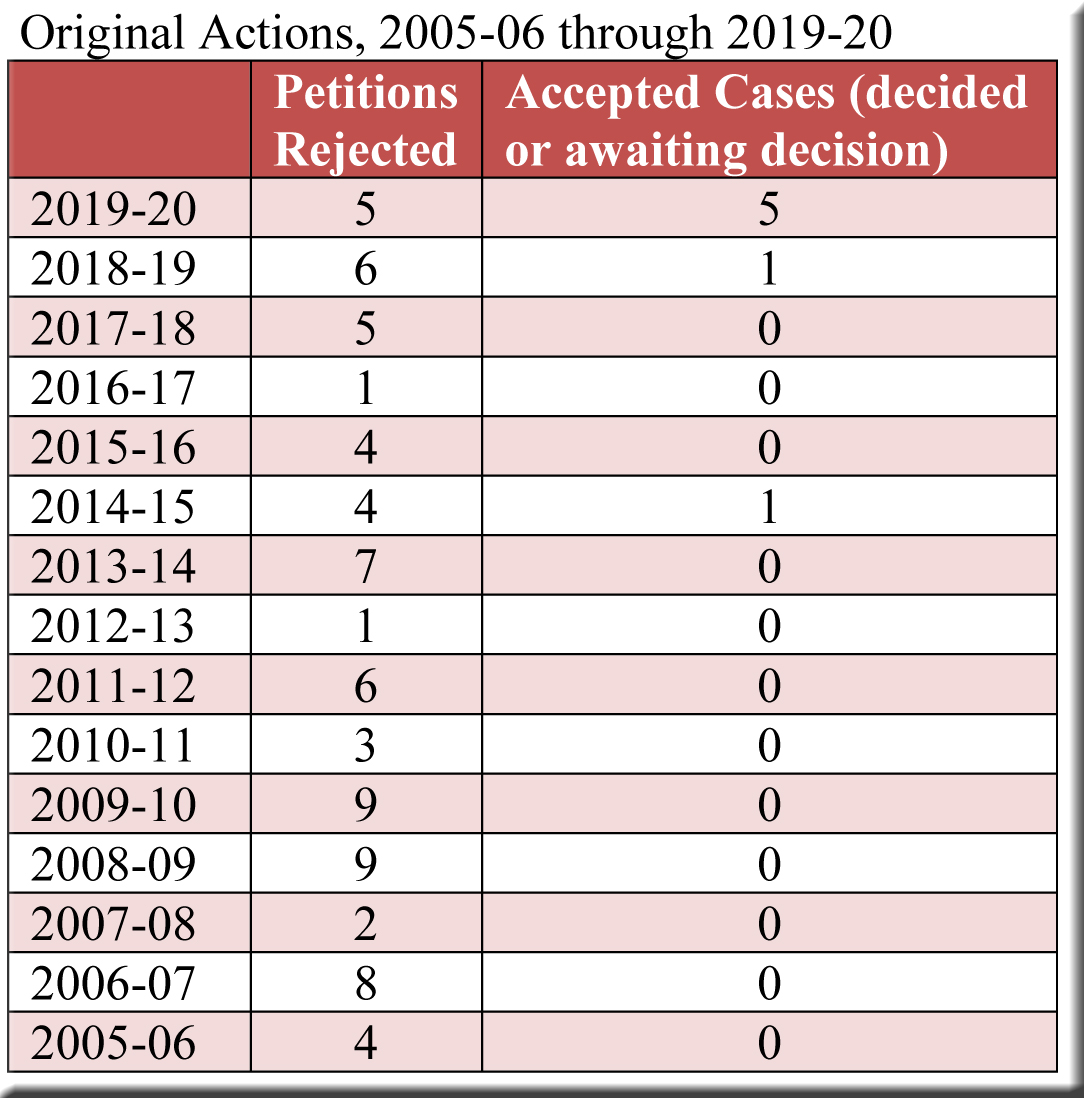

The State Bar also describes them as “rarely invoked,” and, indeed, they have been extremely unusual—until last summer. This is strikingly evident in the following table, for which I collected all original actions listed by CCAP over the last 15 terms and arranged them by date of decision, that is, the date when the court either rejected a petition or issued a decision in a case where an original-action petition had been granted.[3] The figures for 2019-20 include three cases accepted by the supreme court as original actions and awaiting a decision, but they omit Robin Vos v. Josh Kaul, whose original-action petition is still on “hold status.”[4]

Given the supreme court’s conservative majority, it is not surprising that all seven of the successful petitions were filed with the involvement of various conservative entities (most notably the Wisconsin Legislature), and that after the election of Governor Tony Evers, his administration has been the primary target. The cases focus on the spring election procedures and/or measures to cope with the coronavirus outbreak, though the use of partial vetoes has also been challenged.

Even the lone case listed for 2018-19 involved Evers, but with an ironic twist.[5] Here, the conservative Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty (WILL) asked the supreme court to rule that the governor, Scott Walker at the time, had the authority to approve or reject administrative rules proposed by Tony Evers, then Superintendent of Public Instruction. WILL prevailed, though its celebration may have been muted, for Evers had defeated Walker in the November election and supplanted him in the Governor’s Mansion by the time that the court filed its decision.

In view of the unprecedented effectiveness of original actions in briskly summoning the supreme court to redress conservative grievances, it will be interesting to see whether (1) this practice continues at an unusual rate beyond the 2020 election year, and (2) litigants of a different stripe find the tactic similarly inviting, should the court acquire a liberal majority. If either eventuality comes to pass, it will mark a significant departure from the norm displayed in our table—and it will do nothing to discourage commentators of one persuasion or another from applying the label “activist court.”

[1] They include Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, former Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, former Solicitor General Theodore Olson, and former Wisconsin Supreme Court Chief Justice Shirley Abrahamson.

[2] Michael S. Heffernan, Appellate Practice and Procedure in Wisconsin (Madison, WI: State Bar of Wisconsin, PINNACLE, 2020). See the section titled “Original Actions in the Supreme Court.”

[3] Terms run from September 1 to August 31 of the following year.

[4] In two instances—Wisconsin Prosperity Network v. Gordon Myse (2010AP001937-OA) and Green for Wisconsin v. State of Wisconsin Elections Board (2006AP002452-OA)—the court initially granted a petition but subsequently dismissed the original action. Both are counted as “rejected” in the table.

[5] The only other case included in the table’s righthand column (for 2014-15) is the John Doe action in which the supreme court halted an investigation of whether Governor Scott Walker’s campaign circumvented state campaign finance laws.

[…] cases, almost always brought by conservative groups, is itself judicial activism, Ball wrote in a blog post this […]