Enough time has elapsed following the arrival of Justices Rebecca Bradley (3 terms) and Daniel Kelly (2 terms) to form rather clear impressions of their voting records compared to those of the justices whom they replaced (Crooks and Prosser, respectively). This could be done by assessing the four justices’ positions on various issues (Fourth Amendment defenses, med-mal cases, and so on), and we may return to such an approach down the road. Today, however, we’ll look more generally at how these justices voted in relation to their other colleagues over the period beginning in September 2008—at which point the court’s membership remained unchanged until Justice Bradley succeeded Justice Crooks in 2015.

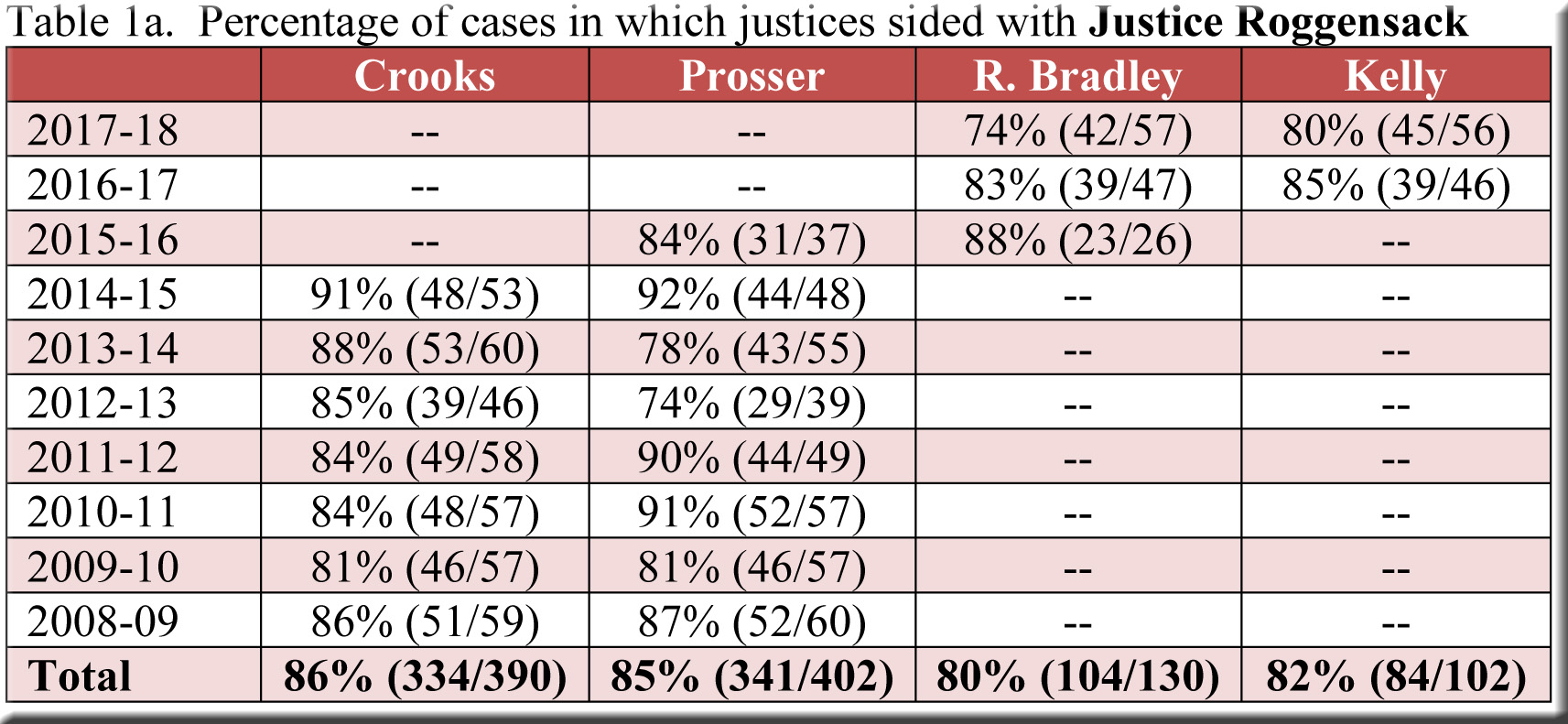

In some respects, the differences are minor between Justices Bradley/Kelly on the one hand and Justices Crooks/Prosser on the other. For instance, both pairs have voted with the court’s three most conservative members (Justices Roggensack, Ziegler, and Gableman) at similar rates. Table 1a shows how frequently each of the four justices voted in accord with Justice Roggensack—86% of the time for Justice Crooks, 85% for Justice Prosser, 80% for Justice Bradley, and 82% for Justice Kelly. For Justice Gableman (Table 1b) the levels of agreement are: Justice Crooks (88%), Justice Prosser (85%), Justice Bradley (80%), and Justice Kelly (84%).[1] It is interesting to note in the tables that Justices Bradley/Kelly joined the court’s most conservative voices a bit less often in 2017-18 than they did in previous terms, but we can’t know yet whether this will endure in 2018-19.

Turning to the question of how regularly each justice voted in the majority, we find again that the percentages for Justices Crooks/Prosser do not differ strikingly from those for Justices Bradley/Kelly (see Table 2). It is true, though, that the percentages for Justices Bradley/Kelly depart furthest in 2017-18 from the averages for Justices Crooks/Prosser, suggesting another indicator to monitor in the months to come.

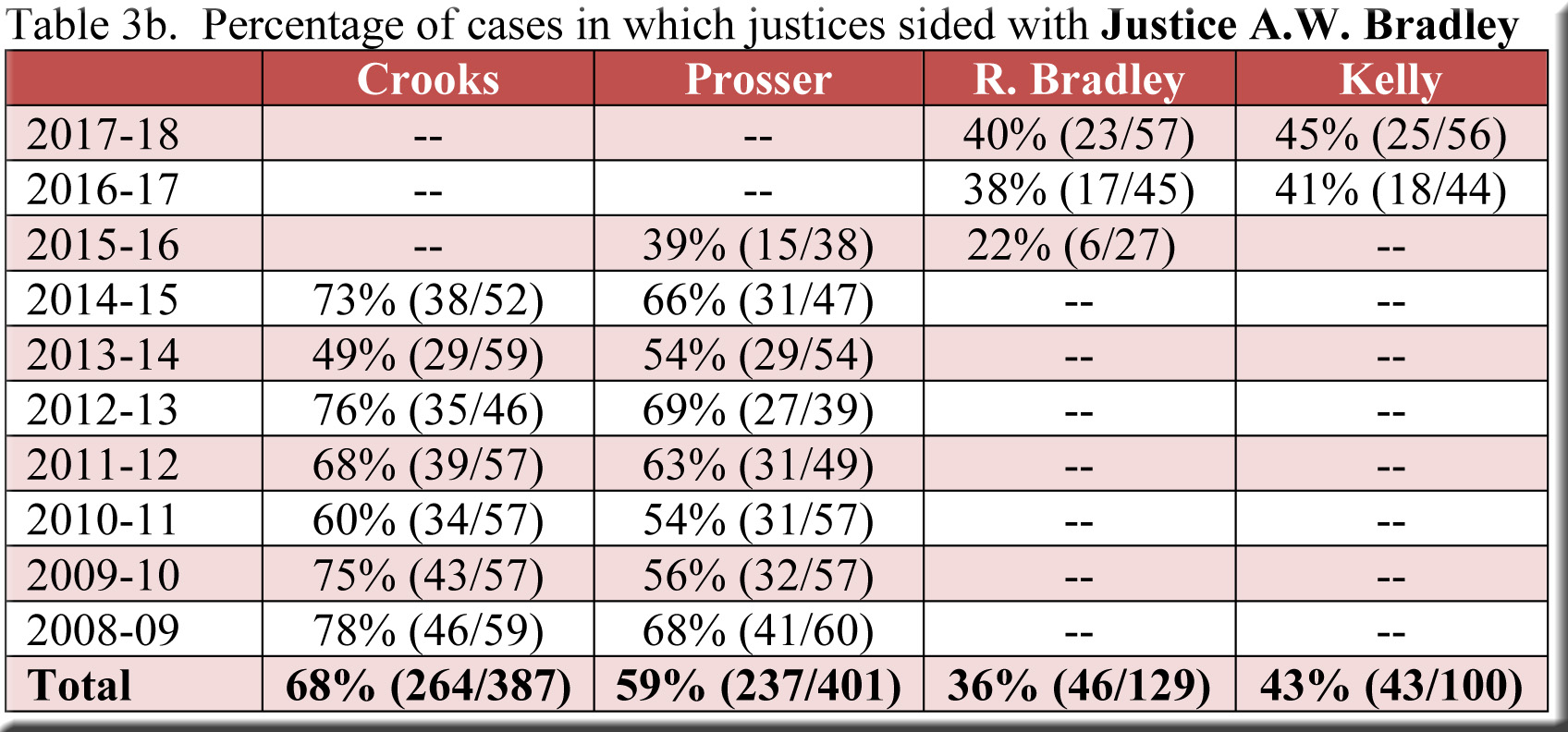

Meanwhile, whatever may transpire during the current term, it is clear that Justices Crooks/Prosser were much more prepared than Justices Bradley/Kelly to vote with the court’s most liberal members (Justices Abrahamson and Ann Walsh Bradley). In Table 3a, which displays the frequency of agreement with Justice Abrahamson, the figures for Justice Crooks (64%) and Justice Prosser (55%) are well above those for Justice Rebecca Bradley (36%) and Justice Kelly (41%)—and the same holds for Justice Ann Walsh Bradley (Table 3b).

Here, again, it’s worth focusing for a moment on the 2017-18 figures for Justices Bradley/Kelly. Not only were they slightly less likely to vote with the court’s conservatives than in previous terms, they were somewhat more likely to vote with the court’s two liberals than they had been in the past.

Taking all of this together, it’s not surprising to find that Justices Crooks/Prosser were considerably more important to the formation of majorities in 4-3 decisions than Justices Bradley/Kelly have been (Table 4).

Conclusion

With the entrances of Justices Bradley and Kelly, the court began what has turned out to be an extended period of arrivals and departures—Justice Bradley for Justice Crooks in 2015-16, Justice Kelly for Justice Prosser in 2016-17, Justice Dallet for Justice Gableman in 2018-19, and a successor for Justice Abrahamson to be chosen next month.

It may well be that the voting differences between Justices Dallet and Gableman, and also between Justice Abrahamson and her successor, will exceed the variation between Justices Crooks/Prosser and Justices Bradley/Kelly. However, it also seems probable that the change in the voting patterns of Justices Dallet and Gableman will occur in the ideologically-opposite direction of the change in votes cast by Justice Abrahamson compared to her replacement. That is, Justice Gableman will likely appear to have been more conservative than Justice Dallet, while Justice Abrahamson will certainly prove to have been more liberal than either of her potential successors. Thus, the combined impact of all this turnover on the bench remains a wide-open question—leaving SCOWstats much to explore in coming years.

[1] Click here for Table 1c, which shows similar numbers regarding Justice Ziegler.

Speak Your Mind