A forthcoming article (“State Criminal Appeals Revealed”) in the Vanderbilt Law Review furnishes the impetus for today’s post on felony appeals in the Wisconsin Supreme Court. Utilizing a dataset released recently by the Bureau of Justice Statistics and the National Center for State Courts—described in the law review article as “the first and only publicly available national dataset on state criminal appeals”—the authors (Michael Heise, Nancy J. King, and Nicole Heise) derived their information from a random, “nationally representative probability sample of criminal appeals resolved in 2010” by state supreme courts and lower appellate courts across the nation.[1]

Here, we will focus on the article’s findings regarding state supreme courts (“courts of last resort” with the discretion to grant or deny review) and, within these boundaries, consider the percentage of appeals that resulted in decisions favorable to defendants. The authors’ sample consists of 1,425 cases, and it excludes capital cases, appeals filed by the State rather than by defendants, and misdemeanor appeals. Review was granted in 89 of these 1,425 cases, and it is this array of 89 cases that attracts our attention.

In nearly half of the 89 cases (40/89 or 45%), the defendants received favorable decisions, and the percentage was a good deal higher (often 100%) in the samples from many individual states. California’s large volume of cases influenced this calculation to the extent that if California is removed from consideration, 52% of the defendants who petitioned successfully for supreme court review in other states obtained favorable decisions. In California, decisions favored only 12.5% of the defendants whose cases were granted supreme court review.

As the authors specify in their first table, the random sample of 1,425 supreme court cases does not include contributions from several states, and one of these non-participants is Wisconsin. For SCOWstats, no further invitation is necessary to compile Wisconsin data and compare them with the national findings summarized above. To remain in step with the article, we will follow the authors’ ground rules—no appeals filed by the State rather than by defendants, and no misdemeanor appeals—and we will confine ourselves, at least at the outset, to decisions filed during the calendar year of 2010.[2] Unlike the article, however, we can examine all cases that meet the criteria, not just a sample.[3]

The difference between the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s decisions and those of the national sample is dramatic. While 45% of state supreme court decisions nationwide favored defendants in felony appeals that they initiated, their success rate in Wisconsin was only 7% (1/14) in 2010. To be sure, the small number of Wisconsin cases decided in a single year prompts the question of whether our impression would change greatly if we expanded our study to include additional years—which we can readily do.

Table 1 provides information for a variety of intervals from 2004-05 through 2016-17 pertaining to felony cases in which defendants were the petitioners.[4] Over the entire period—from a total of 165 cases of this type—19% resulted in favorable outcomes for the defendants. During the last nine terms, when the court turned more conservative (following the replacement of Justice Butler by Justice Gableman in 2008-09), the figured dropped to 13%—in sharp contrast to the “Butler years” (2004-05 through 2007-08) when defendants received favorable decisions in 33% of their appeals.

On the one hand, then, the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s average over these 13 terms is more than two-and-a-half times higher than its figure of 7% for the calendar year 2010 alone. On the other hand, even in the court’s most liberal interlude—the “Butler years”—the portion of decisions that favored defendants (33%) could not approach the national average of 45% in 2010. Assuming that the national dataset underlying the law review article is indeed representative, this is a significant difference.

Finally, it is interesting to observe that in 2016-17, with two new (or newish) justices on the bench,[5] the court’s decisions favored defendants in 31% of these cases, nearly matching the average for the “Butler years.” Of course, the number of cases decided in only one term is small, as it was in 2010, and it bears mention that in 2015-16 none of the six decisions favored defendants. However, the figure of 31% in 2016-17 is conspicuous, at least by recent Wisconsin standards, and it raises two questions. How closely will it resemble the result for 2017-18, and how do the votes of the two newest justices compare with those cast in these cases by other members of the court since 2004-05?

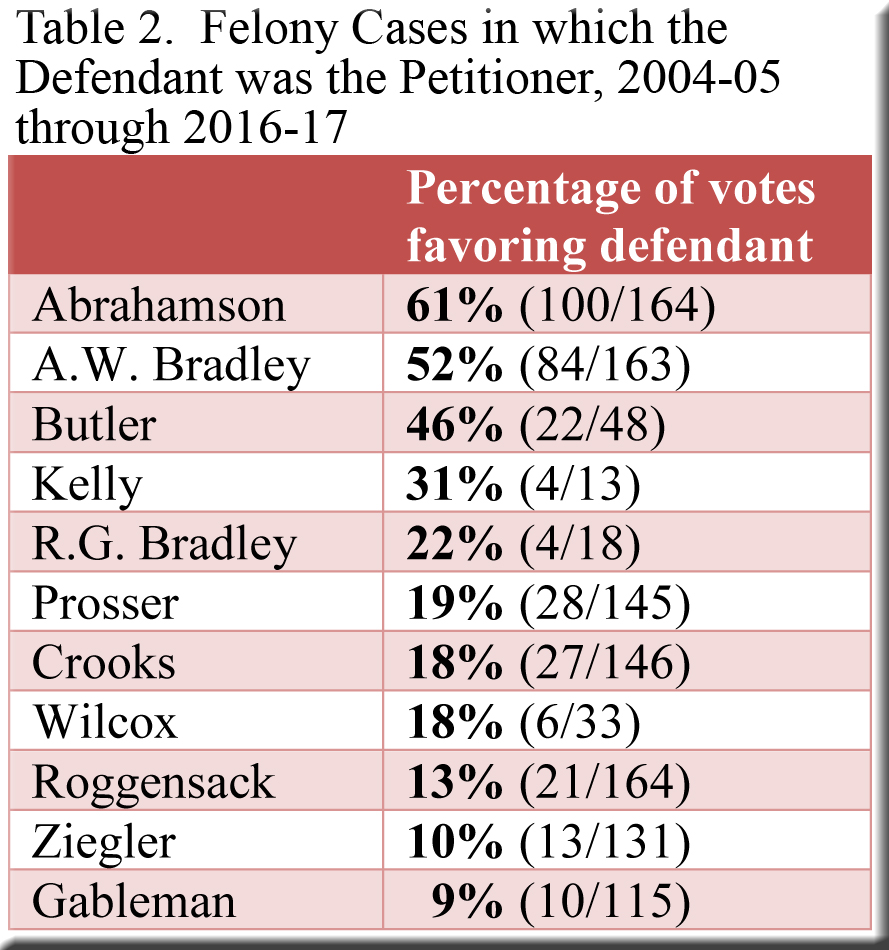

A response to the first question will have to wait for the end of the current term, but the second query imposes no delay, as may be seen in Table 2.[6]

In a pattern similar to that which we encountered when considering Fourth Amendment cases, the two newest justices find themselves in the top half of the table, with percentages higher than those of the two justices whom they replaced (Justices Crooks and Prosser) and well above those for the court’s three established conservatives (Justices Roggensack, Ziegler, and Gableman). As in the Fourth Amendment table, the figure for Justice Kelly is particularly striking. While keeping in mind the caution that his percentage is derived from a single term’s decisions, the question ventured by the Fourth Amendment post (Is Justice Kelly a maverick?) also arises here as we await the results of the 2017-18 term.

[1] I am grateful to lead author Michael Heise, who helped me with questions I had regarding the data.

[2] Similarly, to preserve consistency with the approach adopted by the authors of the law review article, I have employed their method of determining whether a decision was “favorable” for the defendant. In their words: “We defined a decision as favoring the defendant if it involved anything other than an affirmance, a dismissal, a denial of review, or a withdrawal. It is worth noting that our coding convention captures many decisions that a defendant might not necessarily consider to be a ‘win,’ including remands and modest modifications of one of several sentences. The data do not offer a reliable method to distinguish significant modifications or remands from less meaningful ones, and the approach we take comports with prior empirical work examining appeals.”

[3] I identified all cases ending in the CR suffix and then selected those that involved felonies and in which the defendant, rather than the State, was the petitioner (or appellant, in cases accepted on bypass or certification).

[4] Included are decisions involving defendants who were appellants in cases accepted by the supreme court on certification or bypass, and also a very small number of cases in which the defendant was a cross-petitioner or cross-appellant (when both the defendant and the State appealed). I omitted three or four cases that did not lend themselves readily to categorization and also a handful of per curiam decisions. Unlike the calendar-year data for 2010, the data in this table pertain to 12-month terms that begin on September 1 and end on August 31 of the following year.

[5] They are Justice Rebecca Bradley, who replaced Justice Crooks in 2015-16, and Justice Daniel Kelly, who replaced Justice Prosser in 2016-17.

[6] A vote “favoring the defendant” means that a justice joined the majority when the decision favored the defendant, and dissented when the decision was unfavorable for the defendant. As elsewhere in this post, we are considering cases in which the defendant (rather than the State) filed an appeal—almost always as petitioner or appellant, but in three or four instances as cross-appellant or cross-petitioner.

Speak Your Mind