SCOWstats has, until now, measured the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s recent activity against earlier years of the court’s work. Other reference frames are also available, however, and today launches what I hope will be the first in a series of posts comparing the output of the Wisconsin Supreme Court with that of its counterpart in Minnesota—paying particular attention to some of the themes featured in previous posts devoted solely to Wisconsin.

I selected Minnesota because it resembles Wisconsin more closely than most other states—location, climate, economy, demographics, and so forth—while recognizing that it would likely be just as interesting to compare Wisconsin’s supreme court with that of a state that has little in common with the Midwest, especially a state where the justices are appointed rather than elected. That will have to wait for another day, though, as Wisconsin’s western neighbor takes precedence for now over more exotic alternatives.

Although the Minnesota Supreme Court’s procedures may not appear eccentric when viewed from Wisconsin, there are differences between the two courts. For example, while justices are indeed elected rather than appointed to both courts, their six-year terms in Minnesota are four years shorter than in Wisconsin. This, along with Minnesota’s mandatory retirement provision (at age 70), doubtless goes much of the way toward explaining why the turnover among justices has been more rapid there than in Wisconsin during the past decade. Moreover, once a justice joins Minnesota’s court, decisions filed for months thereafter specify that the newcomer did not participate in deciding the case in question because he/she had not been a member of the court at the time of argument and/or submission. In rare instances, when multiple justices recuse themselves from a case in Minnesota, they are replaced by “Acting Justices” (such as a retired justice or a judge from the court of appeals), a practice not shared by Wisconsin. In one case—which challenged among other things the right of a justice, recently appointed to a vacant seat by the governor, to run for election as the “incumbent”—all of the regular justices stepped aside, leaving the decision to a group of five Acting Justices.[1]

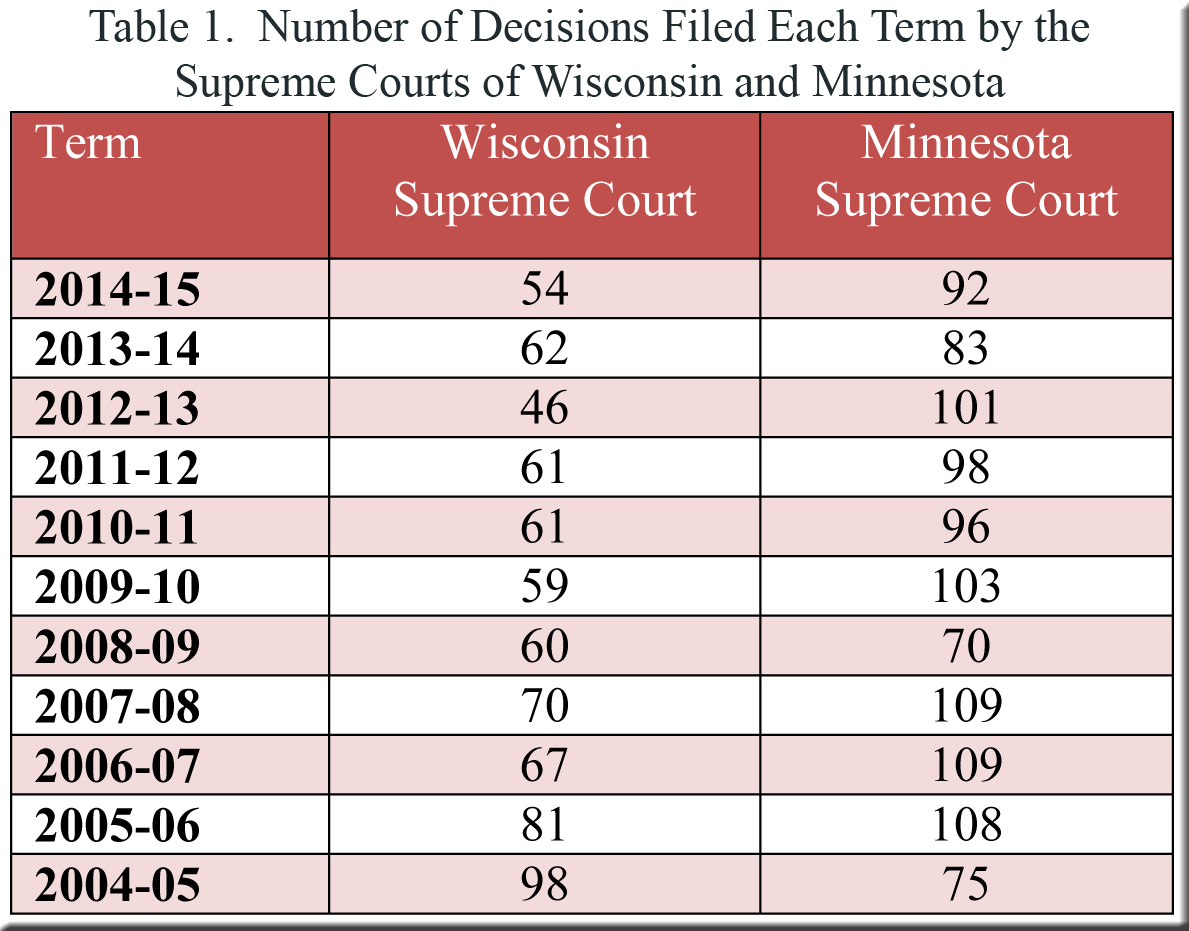

Today’s introductory post focuses on a pair of topics that have figured prominently in SCOWstats of late—the number of decisions filed and their length—both of which reveal a striking contrast between the two courts. In Wisconsin we have seen that over the past two and a half decades the number of decisions per term crested during the first few years of the 21st century when the justices filed an average of slightly over 90 decisions per term, peaking at 98 in 2004-05. Since then, the number has declined steadily to no more than roughly half this figure.

Meanwhile, over the same period, Minnesota’s court has followed a different track. After lagging well behind Wisconsin’s total in 2004-05, the justices in St. Paul often filed over 100 decisions in subsequent terms, far exceeding their colleagues in Madison, as evident in Table 1.[2] (click on tables to enlarge them)

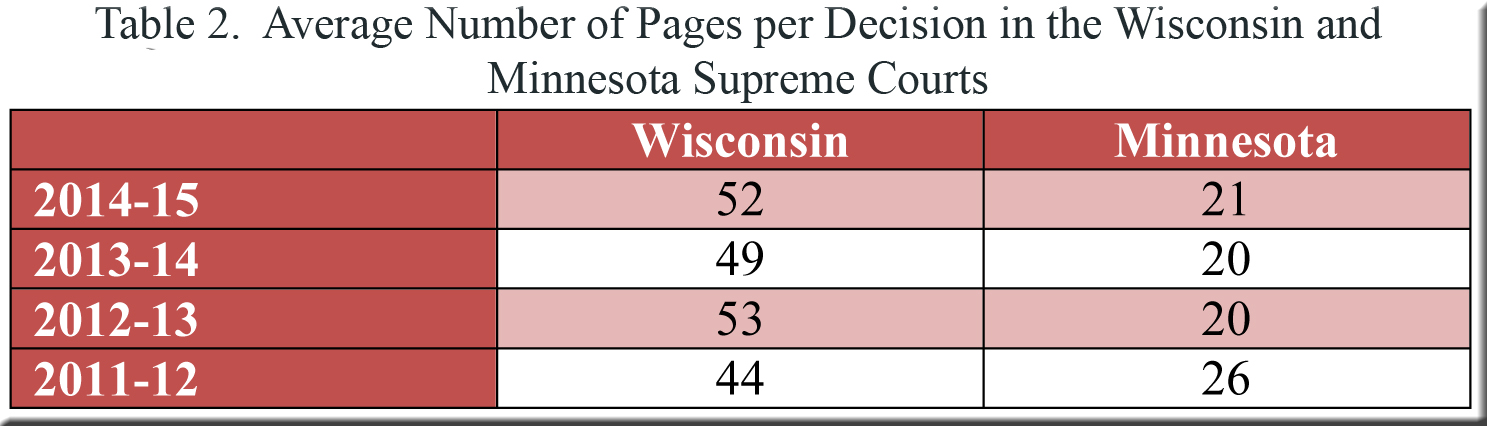

In Wisconsin, the plunging number of decisions filed over the past decade has been accompanied by a marked increase in the number of pages consumed by the decisions that do appear.[3] Given the much larger number of decisions filed in Minnesota, one might guess that they would average fewer pages than those typed in Wisconsin—and such has indeed been the case. I calculated averages covering the past four terms and found the disparity between the two states to be every bit as arresting as it was for the number of decisions. In fact, the average decision in Wisconsin over these four terms required nearly 50 pages—more than double the length (22 pages) of the average decision in Minnesota, which one can ascertain from the information in Table 2.[4]

Separating decisions into their component parts, we find a conspicuous difference for majority opinions—twice as long in Wisconsin—and an even larger one for concurring and dissenting opinions, which averaged three and a half times more pages per decision in Wisconsin than in Minnesota, as shown in Tables 3a and 3b.[5]

One would have to return to the mid-1990s in Wisconsin to encounter a sustained run of opinions whose average length approximated that in Minnesota during the four most recent terms.

Hanging over all of this is the question of whether these numbers favor one state or the other. No doubt an argument could be made that the citizens of Minnesota are better served by a court that resolves far more of their disputes per year than Wisconsinites can expect from their own justices. If the shorter decisions drafted in Minnesota are of sufficient length to furnish clear guidance for future litigants, the advantage would appear to be entrenched in the Land of 10,000 Lakes. However, if opinions from Minnesota can seem hurried or otherwise perfunctory when measured against the opinions flowing from Madison, the legal community of Wisconsin might regard itself as more fortunate than its counterpart just west of the Mississippi.

In other words, while the differences between the two states’ numbers are clear, the conclusions that might be drawn from them are another matter. Is it a case of “better fewer, but better” in Wisconsin—a state where justices might claim to be working at a deliberate pace to craft thorough, well-researched decisions rather than rush them out in assembly-line fashion? Or, in contrast to Minnesota, do Wisconsin’s decisions seem elephantine individually as well as meager in total number? Not to put too fine a point on it, does one state’s approach represent a more commendable model than the other’s? There may be other options as well, of course, but if the choice remains solely between Wisconsin and Minnesota, these two alternatives are nothing if not distinct.[6]

[1] Clark v. Pawlenty (A08-1385), September 5, 2008. There are other differences between the two courts, including the practice in Minnesota of having all first-degree murder convictions sent automatically from the trial courts to the supreme court, and the Minnesota justices’ use of summary affirmances (which are not included in the statistics that follow).

[2] The figures include per curiam decisions from both courts but not the several summary affirmances filed each year by the Minnesota Supreme Court. I have also omitted orders pertaining to (1) disciplinary measures involving lawyers and matters regarding admission to the bar; and (2) various petitions, motions, and other actions that did not yield opinions. Wisconsin decisions may be found on the court system’s website. For Minnesota decisions, click here.

[3] See “Swelling Supreme Court Decisions, 1995-96 through 2013-14” and “Swelling Supreme Court Decisions: An Update for 2014-15.”

[4] The calculations include title pages, majority opinions, and separate opinions. Per curiam decisions are omitted.

[5] Title pages are included as part of the majority opinions. Per curiam decisions are omitted.

[6] As I embark on this comparative project, I would welcome any tips that readers can offer for measuring each of these courts against the other.

Speak Your Mind