With no more decisions expected this term, it’s time to begin our annual exploration of the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s work. Will the dramatic shifts of 2023-24 prove lasting? And what surprises—if any—did 2024-25 have in store?

Number of decisions filed

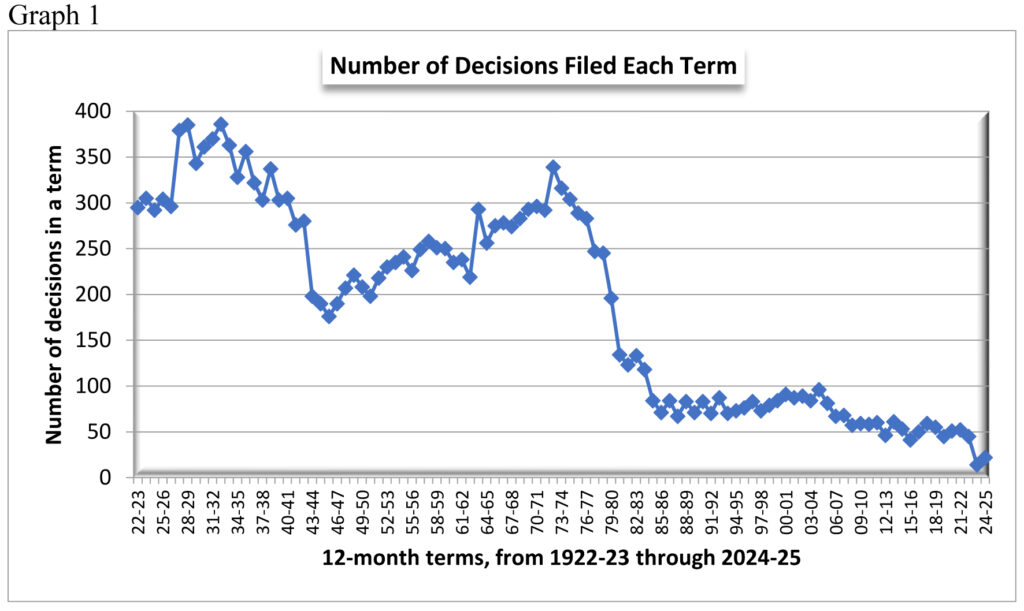

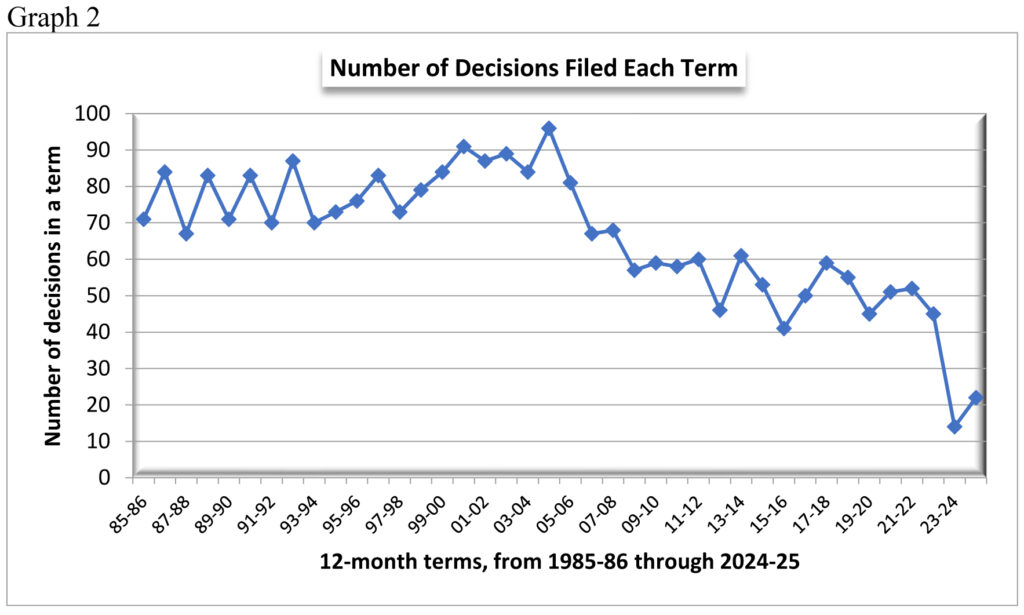

Given the extraordinary drop in the number of decisions filed in 2023-24—only 14, far lower than the total for any other term over the past century (Graph 1)—considerable attention has been focused on the quantity of decisions that would be issued this term. As it transpired, the figure bounced back to 22, which can be viewed as both a significant increase (roughly 50% more decisions than in 2023-24) and, at the same time, a total 50% below the average for recent years prior to 2023-24 (Graph 2).[1] Thus, our saga continues: Will next year’s graph take another sharp jump upwards, or downwards, or begin to establish a new (modest) normal of between 20 and 30 decisions per term?

Length of decisions

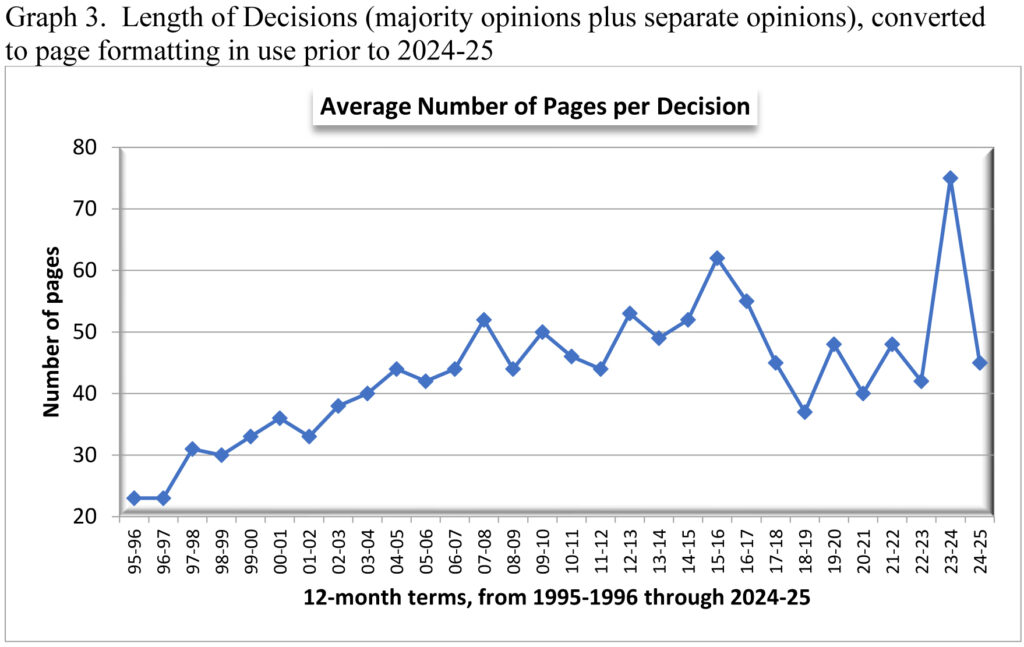

One factor that may have influenced the plunging number of decisions in 2023-24 was their extreme size—75 pages on average, well above the norm for several preceding terms, which did not reach 50 pages. For those wondering whether bulging decisions would persist in 2024-25, the answer is not immediately clear from the court’s website.

More specifically, the court adopted a new style for its decisions in 2024-25 that generates pages containing slightly over 50 percent more words than did pages from earlier terms. Consequently, in order to compare the length of 2024-25 decisions with those of previous terms, we must estimate the average number of words per page in a 2024-25 decision and then calculate how many pages formatted in the older style would be required to hold the same quantity of words. This conversion reveals that decisions averaged 45 pages (old style) in 2024-25, a substantial reduction from the magnitude to which they had ballooned the year before, and a return to the customary range of recent years (Graph 3).[2]

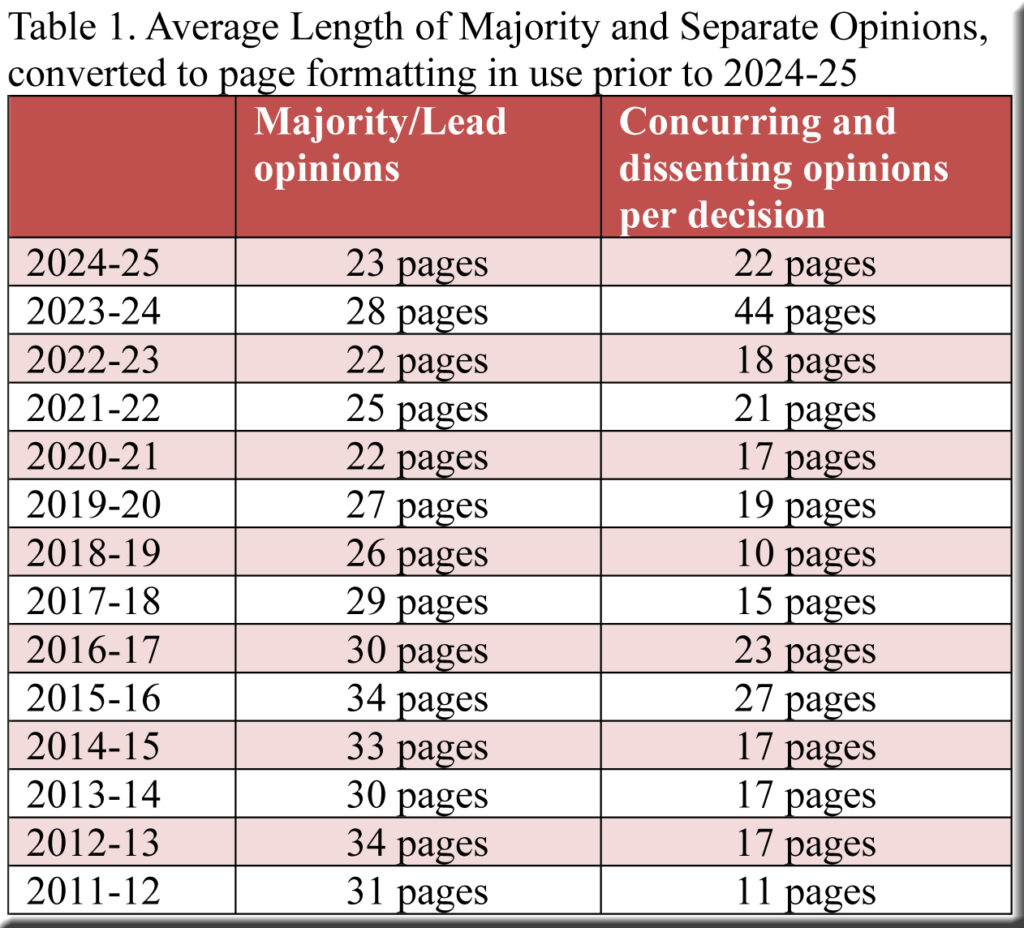

In 2023-24, separate opinions (concurrences and dissents) were the main contributors to the decisions’ outsize bulk (Table 1), but this noteworthy development did not continue in 2024-25. As the table demonstrates, the average length of separate opinions per decision reverted to normal.[3]

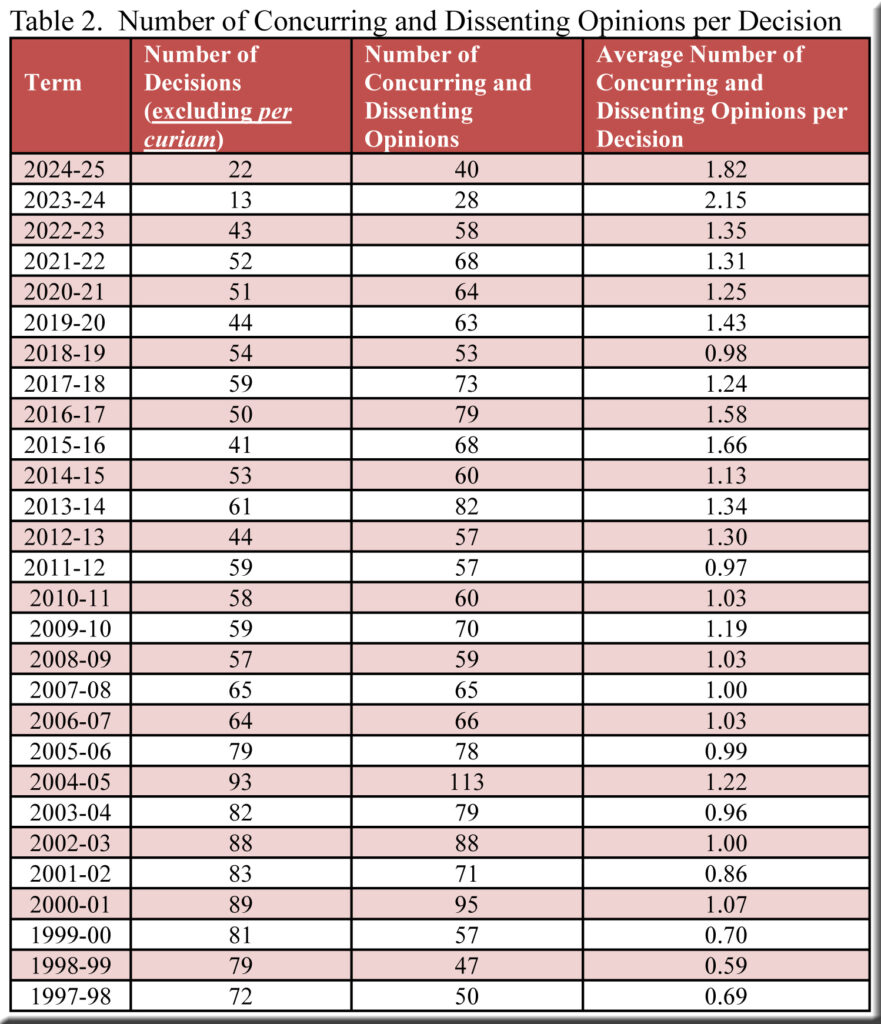

Average number of separate opinions per decision

Much as they did in 2023-24, separate opinions populated practically every decision filed in 2024-25. Only two of the term’s 22 decisions contained no concurrences or dissents, and, overall, the justices averaged almost two separate opinions per decision. This nearly matched the remarkable average (2.15 separate opinions per decision) in 2023-24, surpassing the average for all other years in Table 2.

Although significant, this frequency of separate opinions does require caution if one seeks to present it as the primary cause of the court’s meager output over the past two terms. The justices did indeed write more separate opinions per decision in 2023-24 and 2024-25 than ever before, but the total number of these opinions did not approach the number of separate opinions filed in preceding terms (Table 2).

Also, the total number of pages devoted to separate opinions in 2023-24 (575 pages) and 2024-25 (490 pages)[4] pales before the totals for 2022-23 (772 pages), 2021-22 (1105 pages), and 2020-21 (850 pages)—terms when the court’s output eclipsed that of 2023-24 and 2024-25. In other words, in years when the justices were filing more than twice as many decisions as in 2023-24 and 2024-25, they did so while authoring many more separate opinions, totaling many more pages. Thus, other factors, not just the prevalence of separate opinions, doubtless contributed to the court’s unusually slim yield in 2023-24 and 2024-25.

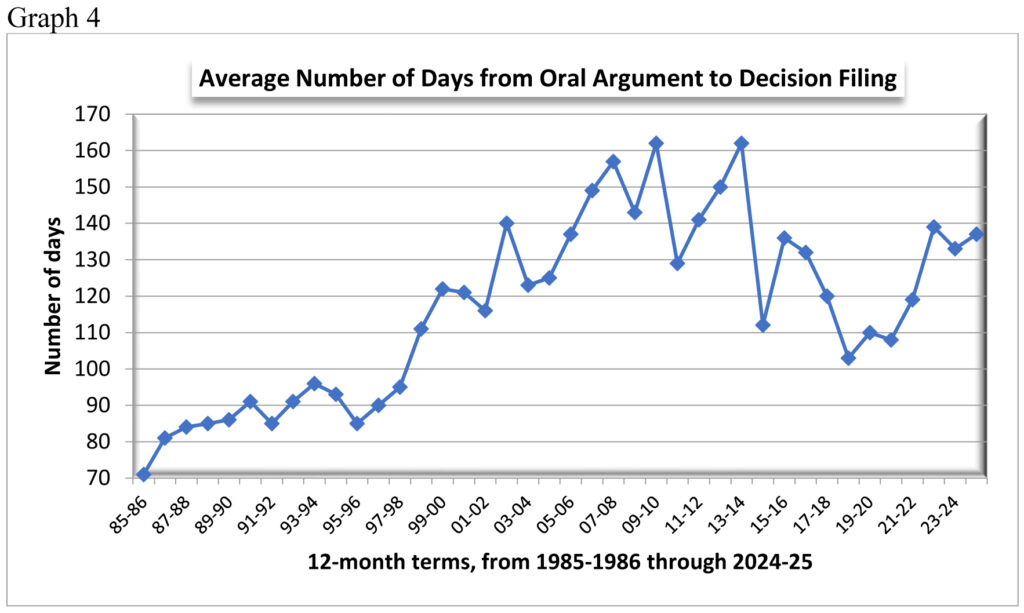

Days to decision

One could speculate, as we did last year, that the writing and circulating of concurrences and dissents in virtually every case would delay the “processing” of decisions following oral argument. However, the average period between oral argument and decision filing in 2024-25 (137 days) fits comfortably within the range for the past 20 years (Graph 4). It seems plausible to suppose that the pervasive separate opinions in 2024-25 (and 2023-24) were balanced by the small number of decisions, keeping the average number of days to decision within the normal span. Had the justices issued, say, twice as many opinions, most with similarly high levels of internal disagreement, the graph might have looked quite different.

Conclusion

The 2024-25 term marked a rebound in output and a retreat from the extremely long opinions of the prior year. Yet the high rate of separate opinions and the (still) low number of decisions leave important questions open regarding the nature of the Court’s practices. Next term may provide further insight into whether we are witnessing transient fluctuations or the emerging contours of new institutional behavior.

[1] The total of 22 decisions does not include a per curiam order denying Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s request to be removed as a candidate for President on the November ballot. Nor does it include Scot Van Oudenhoven v. Wisconsin Department of Justice (dismissed as improvidently granted) and Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin v. Joel Urmanski (dismissed as moot because of the decision in Kaul v. Urmanski).

[2] These figures combine majority opinions and separate opinions. For terms prior to 2024-25, the figures include the page or two at the beginning of decisions that list the parties and the attorneys. This information is not provided in the newly-formatted decisions introduced in 2024-25. Per curiam decisions are omitted.

[3] To be clear, the figures for separate opinions are not the average length of a single concurrence or dissent. They are the average number of pages per decision of concurrences and dissents combined. The averages for both majority opinions and separate opinions are rounded to the nearest page. The averages for majority opinions prior to 2024-25 do not include the page or two at the beginning of decisions that list the parties and the attorneys (as noted above, this information is not provided in the newly-formatted decisions introduced in 2024-25).

[4] This is the total after converting to the page formatting in use prior to 2024-25.

Speak Your Mind