Who can doubt that technology is supplanting human beings as an arbiter of our endeavors. Whether replacing baseball umpires calling balls and strikes, HR personnel ranking job candidates, or university professors grading students’ work, such developments are proliferating along with our embrace of artificial intelligence (AI).

Could the day be far off when AI supersedes corporeal judges? After all, an artificial judge would be incredibly fast, tireless, consistent and, it is said, free of human emotions and biases. Current US Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts has likened a good judge to an umpire—a neutral figure who does not let personal penchants shape decisions[1]—and some may contend that AI can (or soon will) fit that requirement better than humans.

Indeed, countries around the world are already experimenting with AI to help judges, and AI-assisted arbitration platforms are gaining prominence. Emboldened by this, let’s try an experiment that enlists Google’s NotebookLM to scrutinize the briefs in Wisconsin Supreme Court cases and appraise the persuasiveness of the parties’ arguments. Not only can NotebookLM read a set of briefs in just a few seconds, it then explains in considerable detail which party was most convincing.[2] Although these “verdicts” are based on the parties’ briefs alone (not oral arguments)—and bearing in mind the familiar cautions associated with AI output of any sort—it should be interesting to compare NotebookLM’s conclusions with the positions taken by each of the seven justices.[3]

2023-24

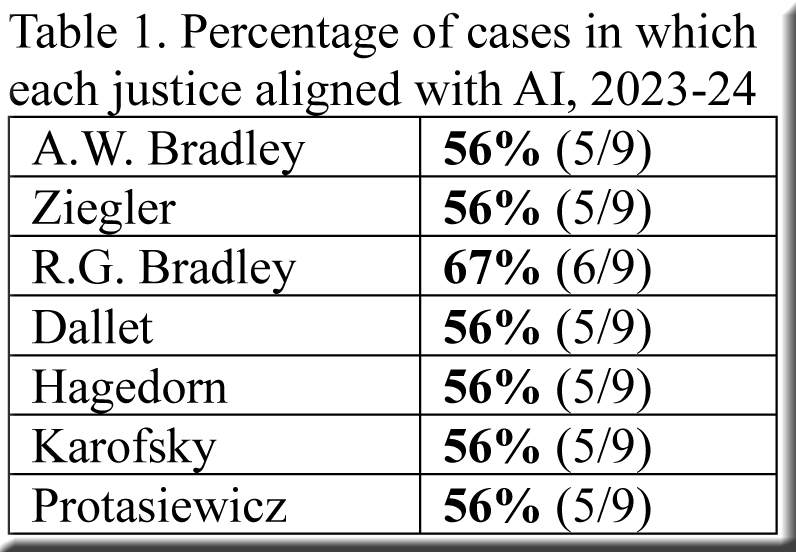

The most recent term, in which only 14 decisions were filed, does not offer much to process, but we’ll start here because the term featured some provocative cases still fresh in memory. After trimming the total of 14 cases down to nine (omitting four “confidential” cases where briefs are unavailable and a per curiam outcome), we find that the rulings in the supreme court’s majority opinions align with NotebookLM’s assessment of the briefs in five (56%) of the nine cases.

While nearly all justices had identical alignment percentages, as shown in Table 1, they did not all side with AI’s judgments in the same cases (Table 2).

2015-16

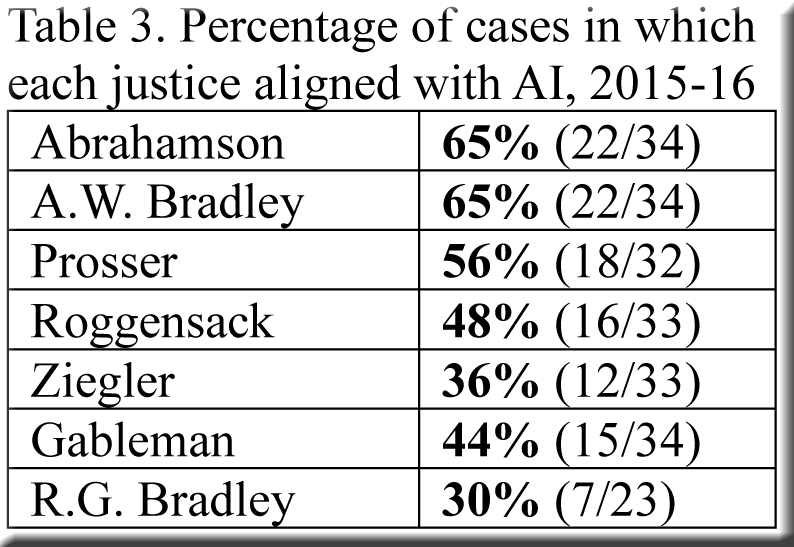

Given the dearth of cases in 2023-24, I decided to choose at random an earlier term, 2015-16, whose larger volume of decisions would furnish more room for exploration. After removing a handful of cases,[4] we are left with a set of 34—and of these, the supreme court’s majority opinions aligned with AI’s reading of the briefs in only 15 (44%).

Unlike 2023-24, when the alignment percentages for individual justices scarcely varied, the range among the justices was substantial in 2015-16 (Table 3).

Civil cases, 2015-16

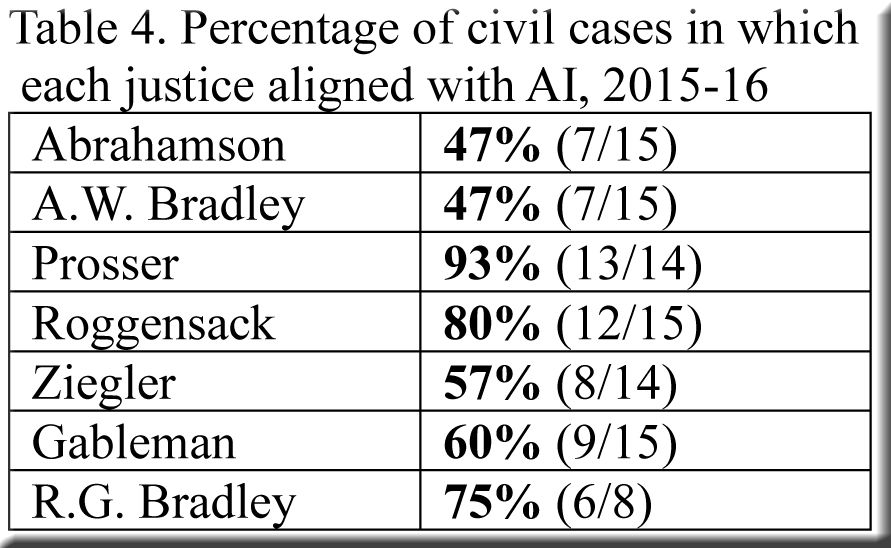

The total of 34 cases suffices to yield viable subsets of 15 civil cases and 16 criminal cases (after subtracting 3 cases that seemed “politicized” or otherwise unsuitable).[5] In the 15 civil disputes, the supreme court majority concurred with AI much more frequently—two-thirds of the time (10/15)—than in the full set of 34 cases, and the alignment of individual justices in civil cases (Table 4) differs markedly from that in previous tables.

Criminal cases, 2015-16

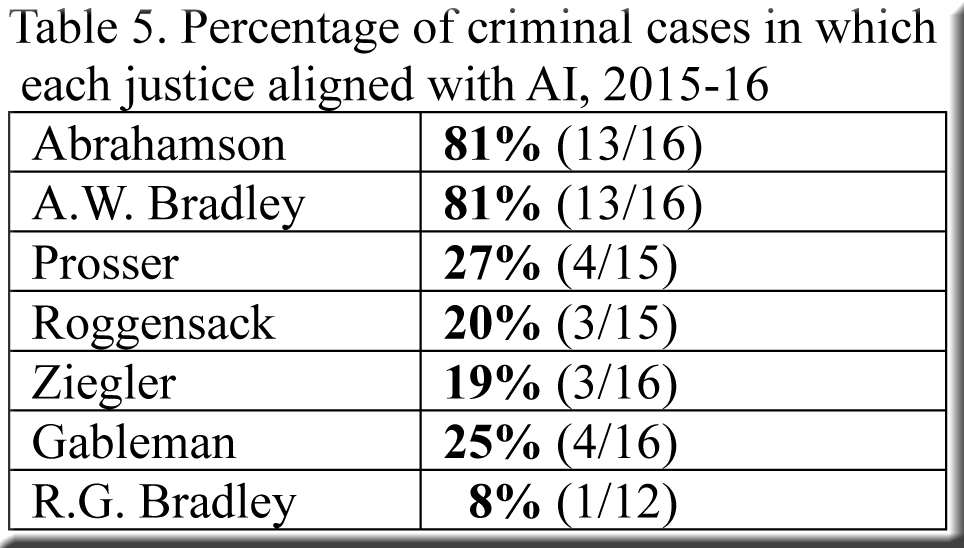

While AI generally sided with the court’s majority in civil cases, it did nothing of the sort in the 16 criminal cases—joining the majority in only four.[6] Moreover, the extreme variation among the individual justices’ alignment percentages in criminal cases (Table 5) far surpasses that for civil cases.

As one can guess from this information along with prior knowledge of the individual justices, a majority of them were much more inclined than AI to favor the State in criminal cases—and indeed they did, agreeing with the State in all but two cases, while AI did so in only two.[7] Public defenders naturally found the sledding tough in these conditions, with the court’s majority siding with them in just one of their six cases. They might well have fared better in an AI courtroom, as NotebookLM deemed their briefs more persuasive than the State’s every time.

Conclusion

For better or worse, AI has already been used to compose briefs and, as we have seen, to evaluate them. Nor is it difficult any longer to imagine a future in which AI not only assesses oral arguments but also conducts them—not unlike two computers competing against each other in chess. If something of the sort comes to pass, with AI court commissioners screening AI-generated petitions for review at lightning speed, the supreme court could handle a breathtaking number of cases each year.

In addition to the vast number of lawsuits resolved by an AI supreme court, other advantages suggest themselves. There would be no need for massively expensive supreme court elections, and controversies involving recusal might subside. However, it’s by no means clear that the new AI supreme court would be less “partisan” or “political.” For instance, disputes would doubtless remain over the algorithms guiding our new AI justices: How much weight should they give to factors of one sort or another? How frequently should they be reprogrammed, and by whom?[8] Perhaps competing interests would even insist on having multiple AI justices on the court, each programmed differently, as a compromise.

Such prospects may feel remote, but they are no more astounding than current technology would have seemed early in the court’s history.

[1] John G. Roberts Jr., Confirmation Hearing on the Nomination of John G. Roberts, Jr. to be Chief Justice of the United States, 109th Cong., 1st sess., September 12–15, 2005 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2005), 55.

[2] Here are two examples of NotebookLM’s “verdicts”—one in State v. Mastella L. Jackson and another in David M. Marks v. Houston Casualty Company.

[3] If a case attracted amicus briefs, I did not include them. Perhaps I’ll return to the project and add amicus briefs to see if they ever make a difference as far as NotebookLM is concerned.

[4] These include two per curiam decisions, a “confidential” case, a few where the justices’ decisions were fragmented, and a case where the justices sided with the state on both issues presented while AI favored the state on one issue and the petitioner on the other.

[5] The three “politicized” cases are Peggy Z. Coyne v. Scott Walker; Albert D. Moustakis v. State of Wisconsin Department of Justice; and Milwaukee Police Association v. City of Milwaukee. AI agreed with the justices in the first case but not the other two.

[6] These include cases with CR suffixes and a few that involved collateral attacks on underlying criminal convictions.

[7]Usually, the Attorney General’s Office represented the State, though in City of Eau Claire v. Melissa M. Booth that role was played by the Eau Claire District Attorney’s Office.

[8] For an extended discussion of such issues, see Sir Robert Buckland, “AI, Judges and Judgement: Setting the Scene,” Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government, Harvard Kennedy School, November 2023.

Speak Your Mind