Observers of the US Supreme Court have devised methods for determining which justices author the most consequential majority opinions. For instance, cases described as unusually “salient,” “significant,” or “important” have been identified by the frequency with which they are mentioned in the New York Times and other media shortly after the decisions are released. Recently, attorney Bill Tyroler kindly brought to my attention a different technique for assessing the importance of US Supreme Court decisions and wondered if it could be applied credibly to the justices in Madison.

Specifically, Bill directed me to a post by Adam Feldman on Empirical SCOTUS that proposed a ranking method based on four aspects of a decision: (1) its length (including separate opinions); (2) the number of amicus briefs; (3) the number of separate opinions; and (4) the vote margin. In other words: the longer a decision,[1] the more amicus briefs it attracts, the larger the number of separate opinions it includes,[2] and the closer the vote,[3] the more likely the case will appear significant.[4] Rather than summarize the defense of this approach presented in Feldman’s post, we’ll test it on the Wisconsin Supreme Court to see if it generates results that seem plausible.

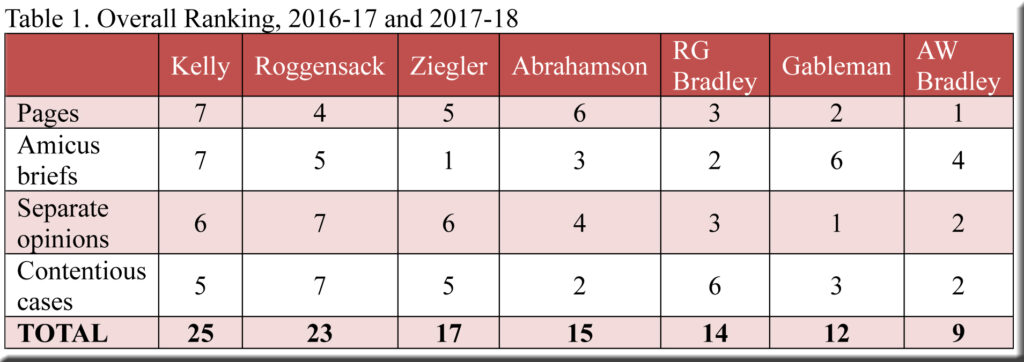

2016-17 and 2017-18

Let’s begin with the two terms where the conservatives’ ascendancy reached its peak—when two liberals (Justices Abrahamson and AW Bradley) were nearly eclipsed by Justices Roggensack, Ziegler, Gableman, RG Bradley, and newcomer Daniel Kelly, appointed to replace retiring Justice David Prosser. During these years, one would expect to find conservative justices authoring the lion’s share of decisions rated most important according to the criteria outlined above—and so they did, as shown in Table 1.[5]

For each of the four categories in the table, the justices are ranked—seven points for the highest, down to one point for the lowest. Thus, the column devoted to decisions in which Justice Kelly wrote the majority opinions indicates: (a) the average length of these decisions was longer than the average length of the decisions for which any other justice wrote the majority opinions—hence, 7 points; (b) the cases in which Justice Kelly wrote the majority opinions included more amicus briefs on average than did the cases for which any other justice wrote the majority opinions—another 7 points; (c) decisions in which Justice Kelly wrote the majority opinions contained more separate opinions on average than was the case for any other justice except Justice Roggensack—6 points for Justice Kelly and 7 for Justice Roggensack; and (d) decisions in which Justice Kelly wrote the majority opinions included enough contentious votes (4-3 or 5-2) to bring him 5 points—behind Justices Roggensack (7 points) and RG Bradley (6 points). The sum of these four scores yields Justice Kelly’s total of 25 points, surpassing the results for his six counterparts.

The table displays the justices in descending order regarding the importance of the cases in which they wrote the majority opinions. Given the conservative dominance during this period, there can be no surprise that Justices Kelly, Roggensack, and Ziegler occupy the highest ranks, with a liberal, Justice AW Bradley, at the bottom. Although two of the five conservatives (Justices RG Bradley and Gableman) reside in the lower half of the rankings, the results overall suggest that Feldman’s method has merit. Let’s see how it does with a different set of justices.

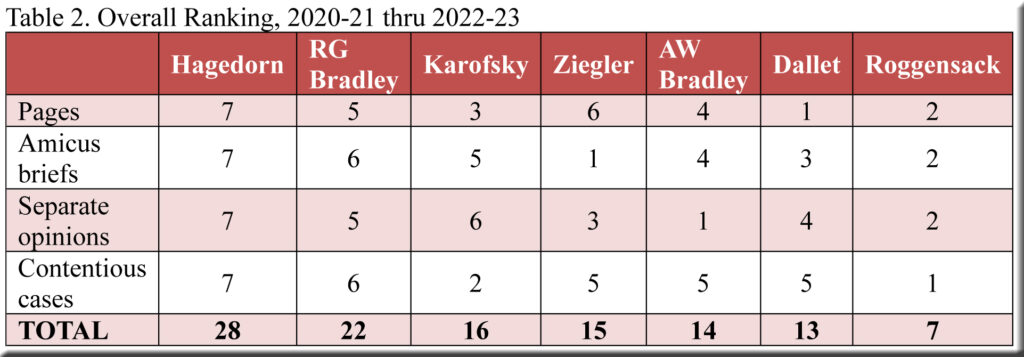

2020-21 through 2022-23

Here the array of justices differs considerably from the seven that populated Table 1, reshaped by the arrival of three newcomers in consecutive years. Justice Dallet replaced Justice Gableman in 2018; Justice Hagedorn succeeded Justice Abrahamson the following term, and Justice Dallet took Justice Kelly’s seat in 2020.

This transformation diminished the conservatives’ preeminence. There were now three liberals (Justices AW Bradley, Dallet, and Karofsky) and three conservatives (Justices Roggensack, Ziegler, and RG Bradley) along with Justice Hagedorn, who leaned conservative early in this period but was not squarely in the conservatives’ camp. The division of the court into liberal and conservative blocs of equal weight produced many 4-3 decisions where Justice Hagedorn was the deciding vote, and he authored more majority opinions than any of his colleagues in these provocative cases. Consequently, we would anticipate him ranking at or near the top in a table constructed according to Feldman’s method—and he certainly does. Indeed, his total of 28 in Table 2 is the highest score possible.

Table 2 contains other signs of change as well, including the fall of Justice Roggensack all the way from the second rank in Table 1 to the very end of Table 2 and a move in the opposite direction by Justice AW Bradley. Meanwhile, another liberal (Justice Karofsky) debuted in the third spot (formerly held by a conservative, Justice Ziegler, in Table 1)—a hint of more dramatic developments to come.

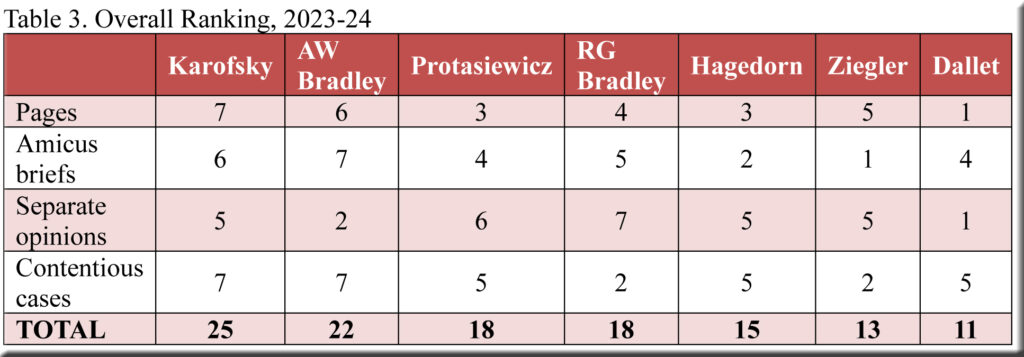

2023-24

After Janet Protasiewicz’s victory in an election conducted to replace the retiring Justice Roggensack, the court began the 2023-24 term with something new—a solid liberal majority. Thus, it’s not astonishing that liberals occupy the two highest ranks in Table 3 (with another liberal, Justice Protasiewicz, tied for third with Justice RG Bradley). Justice Karofsky, in the top spot, matched Justice Kelly’s score in Table 1, only three points lower than Justice Hagedorn’s total in Table 2. As for Justice Hagedorn, no longer needed by the liberals in close votes, we find him all the way down in fifth place, with scarcely more than half his record number of points in Table 2. Liberals, in short, were now writing most of the court’s important decisions as measured by Feldman’s technique.

Although this fits comfortably with the change in the court’s composition, one might not have predicted the outcome in Table 3 for Justice Dallet (part of the liberal majority). She trails not only the other three liberals but the conservatives too. I’m not sure what to make of this (even more unexpected, perhaps, than Justice Roggensack’s position at the far end of Table 2). In any event, the results for 2023-24 must be regarded with particular caution because of the very small sample size. Fortunately for this exercise, the court’s lineup has not changed, so we will have an opportunity to add data from decisions filed in 2024-25 and see if the impression from 2023-24 remains intact. In the meantime, I’d be grateful to benefit from comments that readers may have regarding Feldman’s method.

[1] Feldman counted the total number of words, while I used the total number of pages (given that I had already calculated the page totals for other purposes).

[2] In the very rare instances when two justices coauthored a separate opinion, I counted it as only one.

[3] Feldman counted 5-4 and 6-3 as close votes; for the Wisconsin Supreme Court the equivalent votes are 4-3 and 5-2 (along with some 4-2 outcomes).

[4] According to the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s internal operating procedures, responsibility for writing the majority opinion in a case is chosen by lot among the justices forming the majority.

[5] For fragmented decisions, the justice identified as the author of the lead opinion is credited in this post’s tables.

Speak Your Mind