Four years have passed since our previous post on the Fifth Amendment, so it’s time for an update to see how the justices have responded recently to arguments featuring rights promised to Americans by this amendment—notably, protection from: (1) prosecution for serious crimes without a prior, legal indictment by a grand jury; (2) repeated prosecution for the same offense (“double jeopardy”); (3) involuntary self-incrimination—being forced to testify or give evidence against one’s self; and (4) deprivation of life, liberty, or property without “due process of law” or “just compensation.”

Individual justices

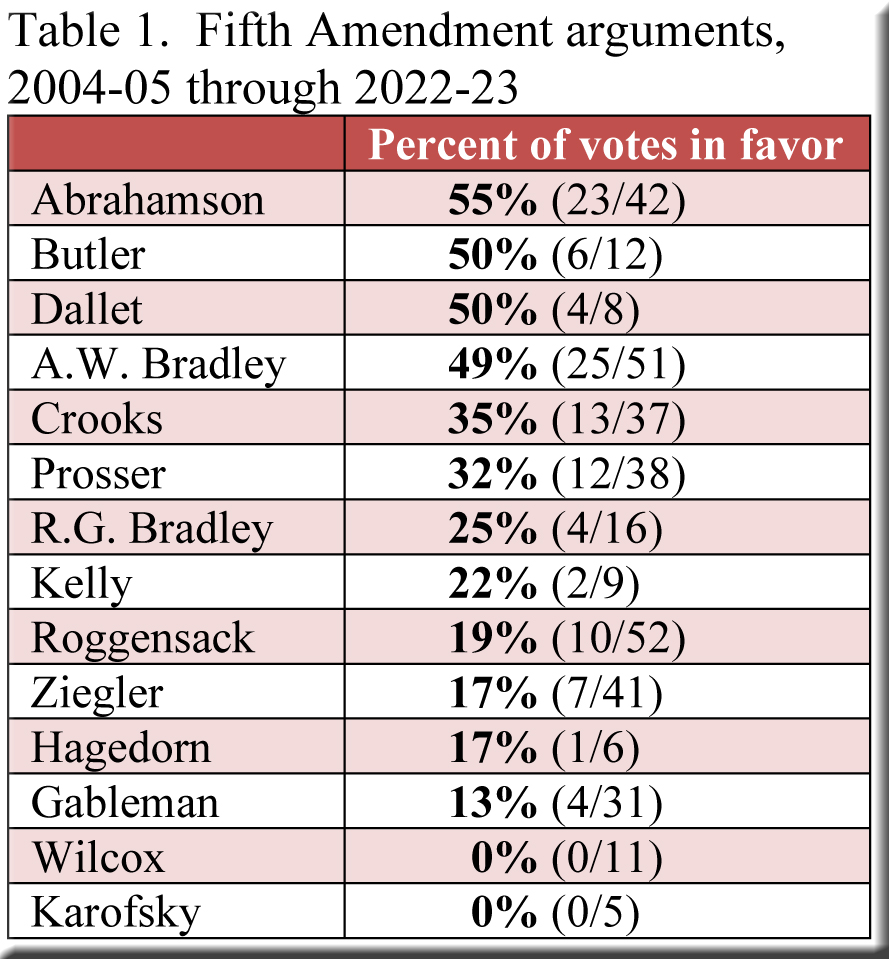

Over the two decades surveyed by this post (2004-05 through 2022-23), the court has accepted Fifth Amendment arguments in 21% of the cases in which these arguments have figured.[1] Of course, the “acceptance rates” for individual justices varied a great deal, as shown in Table 1, with justices regarded as “liberals” approving Fifth Amendment arguments much more often than “conservatives.”[2] Justice Karofsky represents the most striking exception, as she has yet to favor a single submission of a Fifth Amendment defense. To be sure, she has heard the fewest such cases of any justice in the table, and thus her “votes-in-favor” percentage could change significantly in short order. But it hasn’t so far, after three terms on the bench.

Criminal cases and takings claims

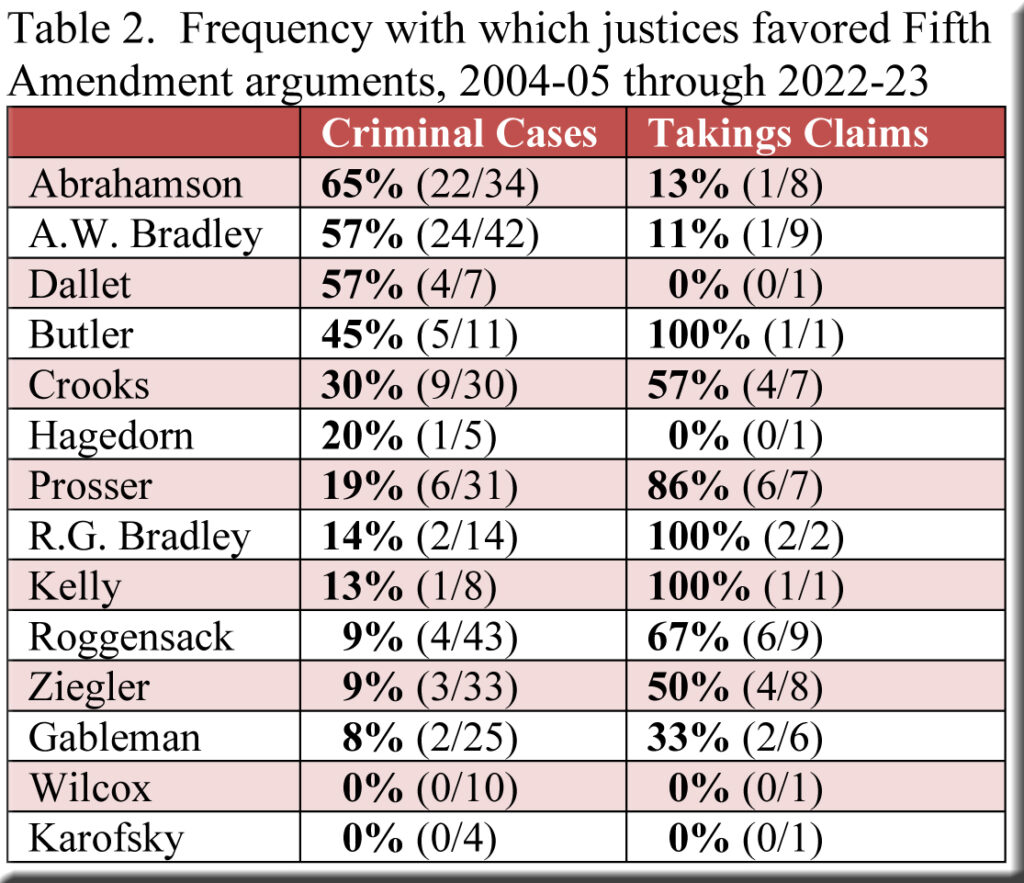

Most Fifth Amendment cases that reach the supreme court concern criminal charges,[3] but a few involve “takings claims”—civil cases in which litigants contend that they have been deprived of property without “just compensation.” Typically, the complaints assert that (1) a government agency has acquired property (via eminent domain proceeding, for example) without fairly compensating the former owner, or (2) the value of an owner’s property has been unjustly diminished by nearby construction.

During the past four terms the justices ruled on only one takings-claim case, and this result (a 4-3 rejection of the Fifth Amendment argument in Christus Lutheran Church of Appleton v. Wisconsin Department of Transportation) has been combined in Table 2 with data from the previous post that separated criminal cases from those presenting takings claims.[4]

In Christus Lutheran Church, the three most consistently conservative justices (Roggensack, Ziegler, and R.G. Bradley) dissented in favor of the takings claim denied by the more liberal majority—a pattern that regularly emerges among justices who have been on the court long enough to have heard several such cases. In other words, conservatives embrace Fifth Amendment arguments much more readily in takings-claim cases than in criminal cases, while the reverse holds true for liberals, as Table 2 demonstrates.[5]

Fourth v. Fifth

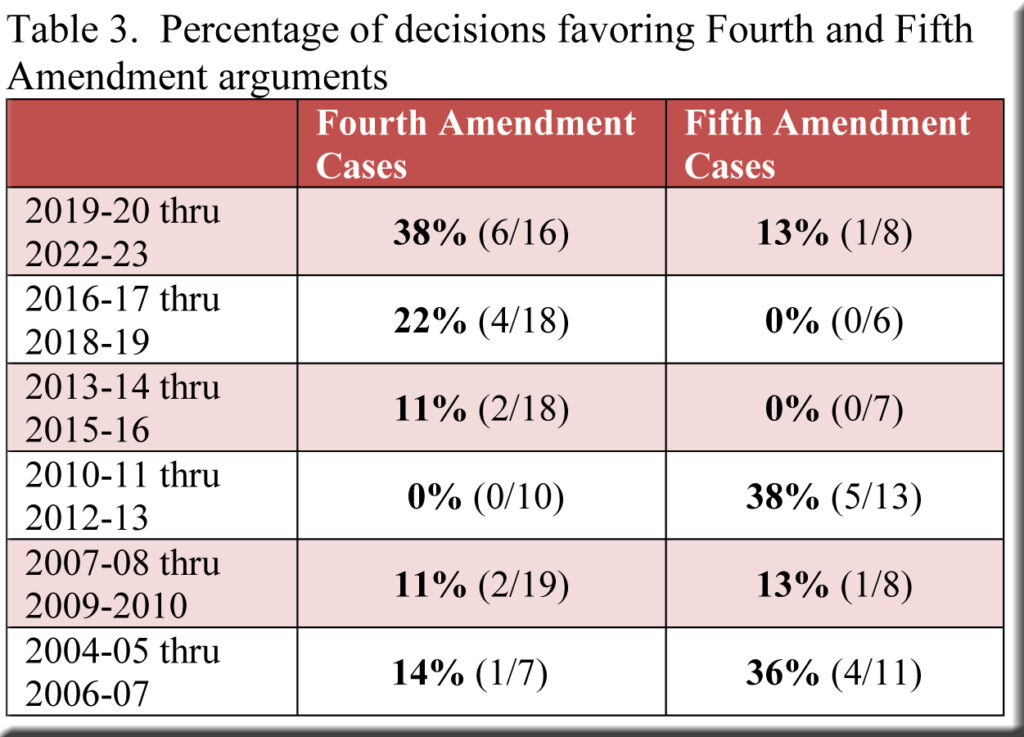

Fifth Amendment arguments experienced a dramatic change of fortune over the past two decades (Table 3). During the first nine terms (2004-05 through 2012-13) they prevailed in 31% of the cases in which they were advanced—an impressive success rate—which then plummeted in the following decade to 5%. This plunge appears even more vivid when contrasted with the outcomes for Fourth Amendment arguments, whose success rate moved in the opposite direction. As detailed in Table 3, attorneys relying on the Fourth Amendment carried the day during the first nine terms in only 8% of their cases at the same time that Fifth Amendment arguments succeeded in 31%. But over the most recent decade these positions flipped, as litigants found Fourth Amendment arguments much more promising (23%) than the meager results (5%) for their Fifth Amendment counterparts.

It’s unclear to me why this has happened, and I’d be grateful if readers could suggest an explanation. Meanwhile, it will be interesting to see if the arrival of a new justice, altering the court’s balance, produces any changes concerning the reception for either amendment in 2023-24 and beyond.

[1] The figures in this post are derived from cases with central arguments pertaining to the Fifth Amendment (and/or equivalent provisions in the Wisconsin Constitution). In cases such as State v. Brantner—where the court accepted Brantner’s Fifth Amendment argument but rejected his venue argument—we are concerned only with the Fifth Amendment argument.

[2] Justice Hagedorn is omitted from consideration in State v. Green because his dissent did not address the Fifth Amendment issue of double jeopardy.

[3] Regarding criminal cases decided in 2019-20 through 2022-23, all the Fifth Amendment issues involved either double jeopardy or self-incrimination.

[4] DEKK Property Development, LLC v. Wisconsin Department of Transportation approaches but does not focus on Fifth Amendment “Taking Clause” arguments, so I have omitted it.

[5] As noted above, the pattern comes into focus once a justice has heard at least a couple takings-claim cases.

Speak Your Mind