Now that two more terms are in the books following our last update on Fourth-Amendment cases, we’ll return to see how receptive the justices have been to Fourth-Amendment arguments recently—and how they compare in this regard to their predecessors on the bench over the past few decades.

Number of Fourth-Amendment Cases

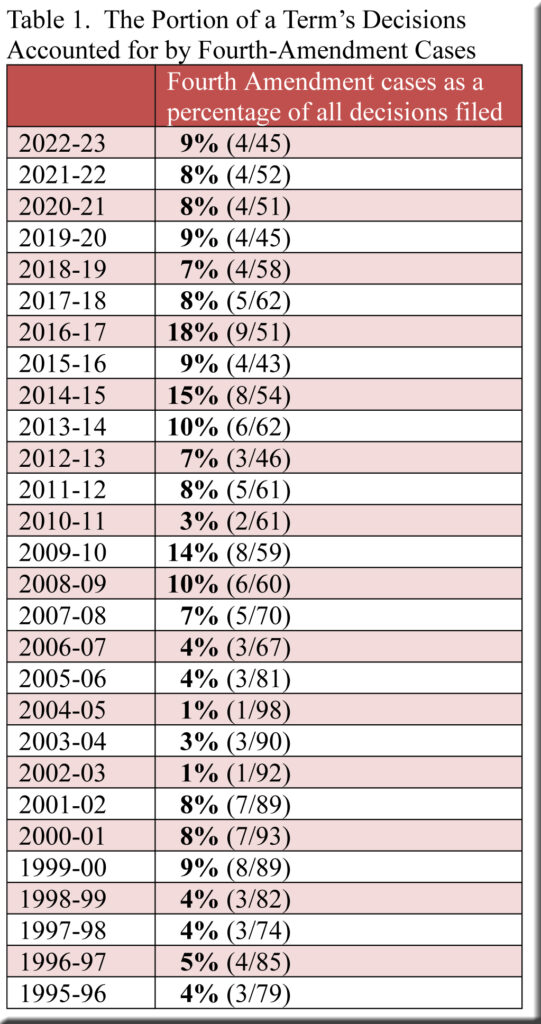

Previous posts have found that the court devoted an unusually large portion (10%) of its docket to Fourth-Amendment cases during the interval from 2008-09 through 2016-17, with the average climbing to 13% during the last four terms in this period. Since then, the share of Fourth-Amendment cases has held at eight or nine percent (Table 1)—less than in peak years, but more than the average of 5% accumulated from 1995-96 through 2007-08.

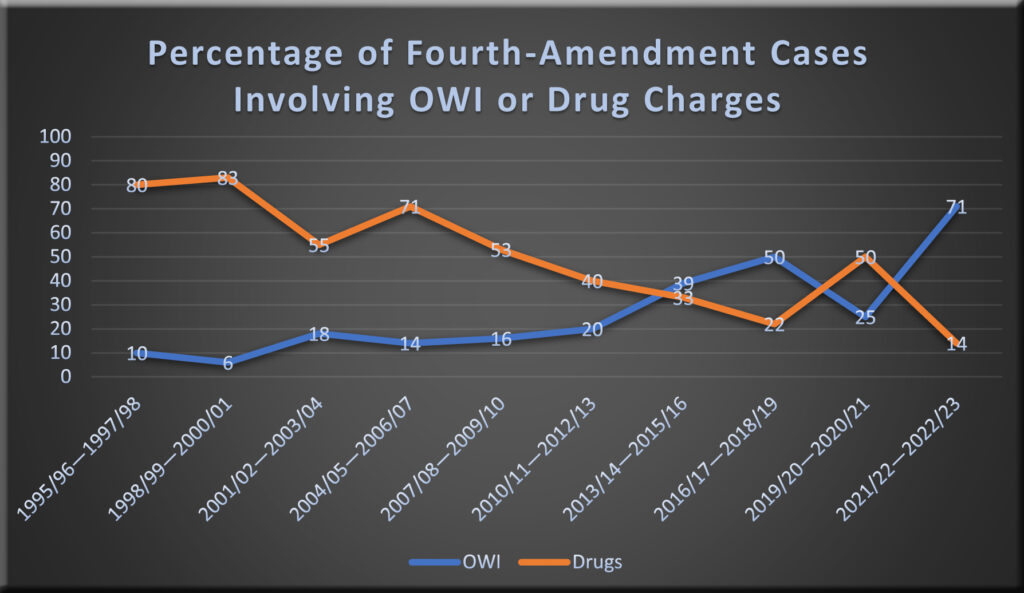

The most common types of Fourth-Amendment cases at the supreme court pertain to drug and OWI charges. For many years the percentage accounted for by drugs towered above the share for OWI, as shown in the following graph. However, the lines began crisscrossing ten years ago and have continued to do so down to the present. During the last two terms, the portion of Fourth-Amendment cases addressing OWI issues (generally involving blood draws) soared to 71%, much higher than it had ever been, while drug cases fell to 14%, their low-water mark for the entire period.[1]

Percentage of Decisions Favorable to Defendants

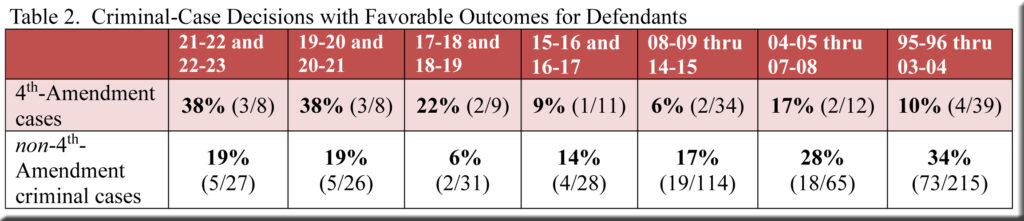

Two years ago, we noticed a striking increase in the success rate for Fourth-Amendment claims, as the supreme court accepted defendants’ arguments in 38% of decisions filed in these cases during the 2019-20 and 2020-21 terms. This far surpassed the percentages for any of the previous intervals covered in Table 2, including the “Louis Butler years” (2004-05 through 2007-08), which have often been cast as the liberals’ high-water mark on the court prior to the arrival of Justice Protasiewicz. Thus, it’s noteworthy to find Fourth-Amendment arguments continuing to succeed at the same rate during the two most recent terms—and raises the question of whether the percentage will change at the hands of the court’s new lineup over the next two years.

For readers not dazzled by the 38% success rate, consider the outcomes displayed in Table 2 for non-Fourth-Amendment criminal cases. While defendants in these cases fared better than those mounting Fourth-Amendment defenses over the first 20 years in the table, that has changed abruptly of late, with defendants in Fourth-Amendment cases currently twice as likely to succeed as those in other criminal cases.[2] This pattern has held for several years and provides another metric for assessing Fourth-Amendment decisions forthcoming from the new roster of justices presently embarked on their first term together.

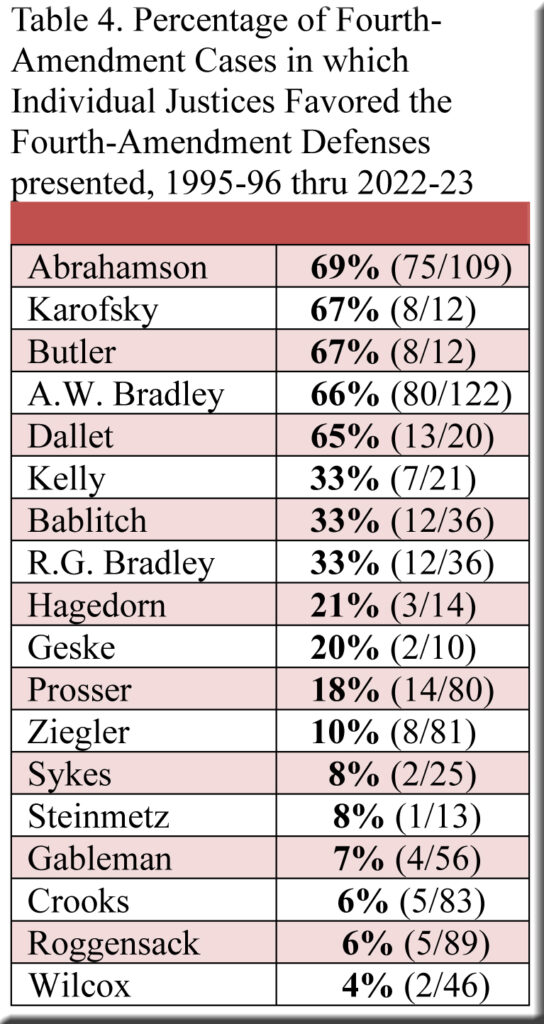

Votes by Individual Justices

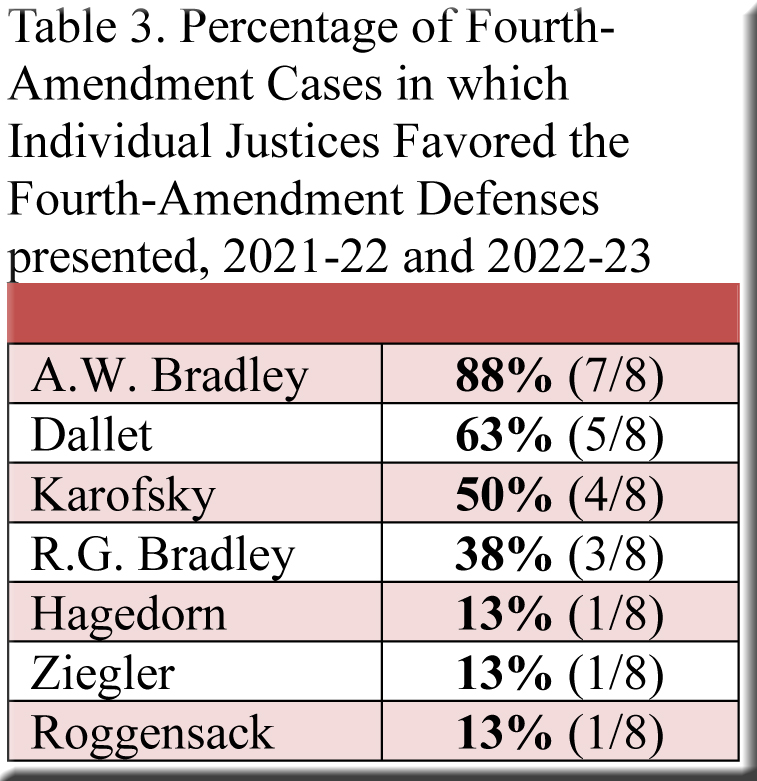

It’s no surprise to observe in Table 3 that the three liberal justices responded much more favorably to Fourth-Amendment arguments than did their conservative colleagues—though the figure of 88% for Justice A.W. Bradley is remarkably high, even compared to those for Justices Dallet (63%) and Karofsky (50%). Readers may also find it interesting that Fourth-Amendment decisions represent an unusual instance in which Justice R.G. Bradley has sided with the liberals a good deal more often than has Justice Hagedorn.

She has done so not only during the two terms covered in Table 3 but over the full period that both have served on the bench—included in the interval spanned by Table 4.[3] Here again, while her 33% acceptance rate of Fourth-Amendment arguments is only half that of the liberals clustered at the top of the table, it exceeds Justice Hagedorn’s rate of 21% by a sizeable margin.

[1] State v. Wilson, which involved a variety of charges—among them both drug and OWI offenses—is omitted in the graph (but it is included in other calculations for this post).

[2] The table includes two non-Fourth-Amendment cases lacking CR suffixes: State v. C. G. (2018AP002205) and State v. X.S. (2021AP000419). It omits two other non-Fourth-Amendment cases—State v. Corey T. Rector (2020AP1213-CR) and State v. Joseph G. Green (2020AP298-CR)—because the decisions were partly favorable and partly unfavorable to the defendants.

[3] Justice R.G. Bradley began serving in the autumn of 2015, and Justice Hagedorn joined her at the start of the 2019-20 term. Justice Roland Day is omitted from Table 4, because the table covers only the last term of his long tenure (1974-96).

Speak Your Mind