Which law schools groomed the oral advocates who appear at the Wisconsin Supreme Court, and where are these law schools most conspicuously represented among the state’s private firms and state agencies? Since our last post on the topic,[1] four terms have passed, leaving abundant data to explore in today’s update.

An overview

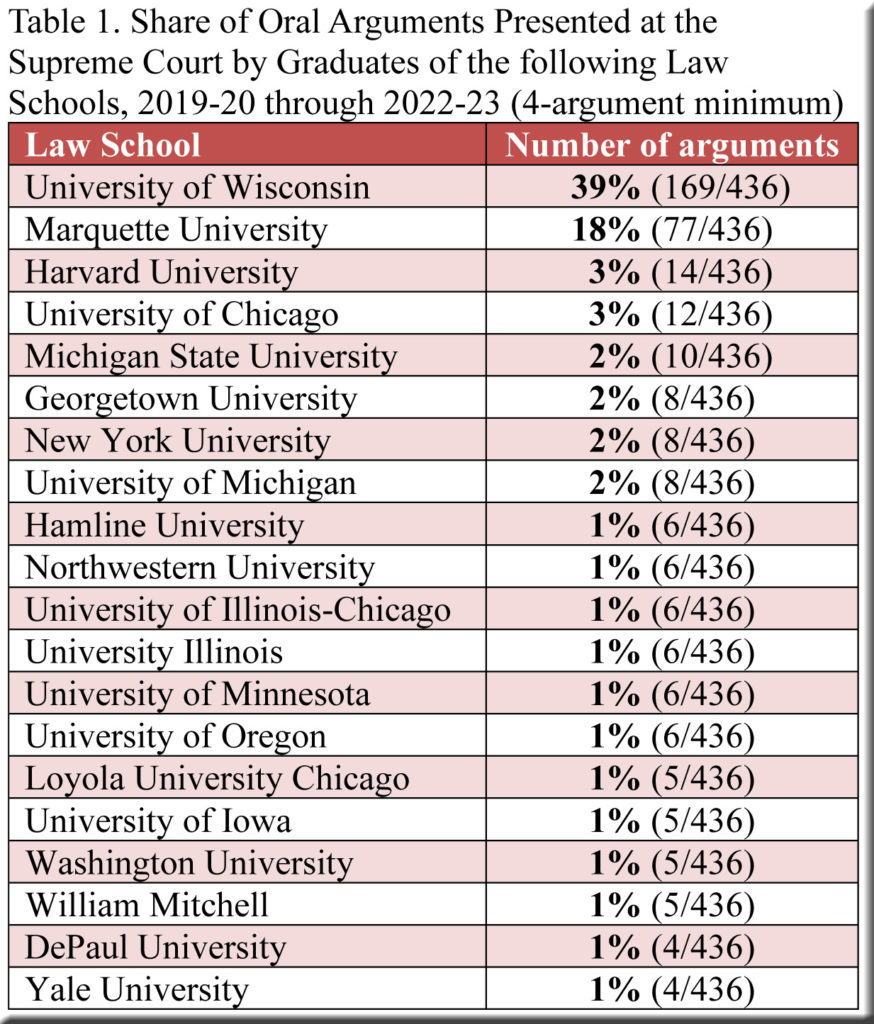

During the four terms under review, attorneys delivered 436 oral arguments, and Table 1 displays every law school whose graduates accounted for at least four (or roughly 1%).[2]

A point of interest concerns the prominence of Marquette University and the University of Wisconsin. The initial post in this series, covering 2008-09 through 2013-14, found graduates from UW-Madison’s law school accounting for nearly half (47%), and those from Marquette nearly a quarter (23%), of all oral arguments. Over the following period, 2014-15 through 2018-19, these figures shrank markedly, to 39% and 19% respectively. In other words, the two schools’ combined share tumbled from 70% to 58%. However, the decline halted during the four terms under scrutiny today, as Wisconsin’s portion remained at 39%, and Marquette’s slipped only to 18%.

Private firms

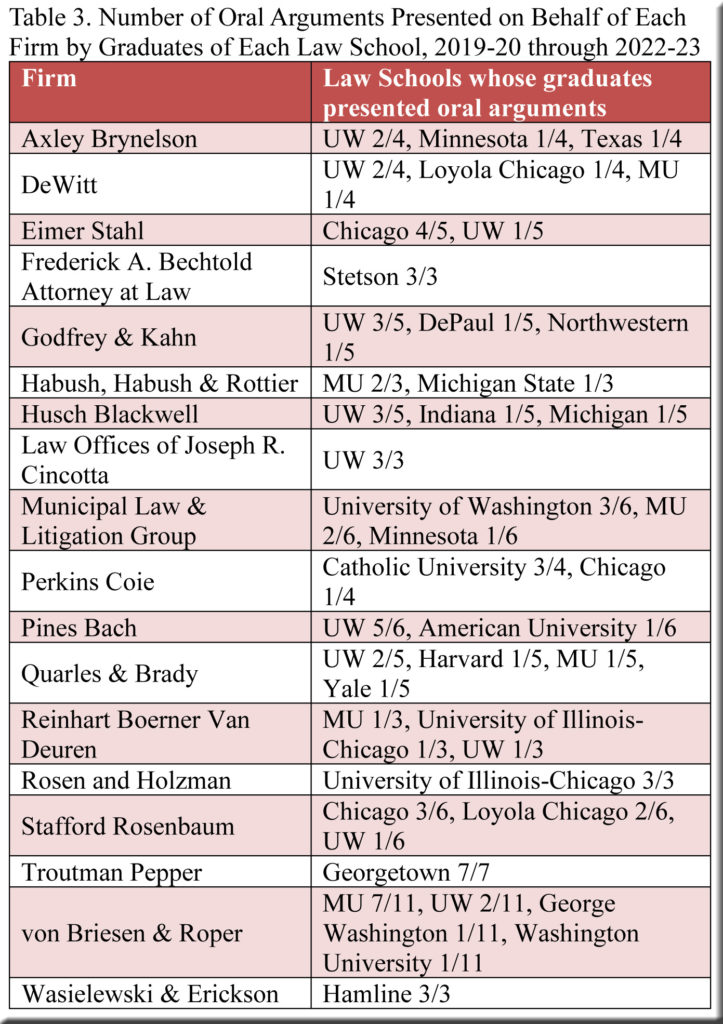

Next, we’ll focus on private firms (that is, excluding government agencies and non-profits) whose attorneys conducted a minimum of three oral arguments out of the total of 436 in Table 1. These criteria yield a set of 18 firms, listed here in alphabetical order: Axley Brynelson ♦ DeWitt ♦ Eimer Stahl ♦ Frederick A. Bechtold Attorney at Law ♦ Godfrey & Kahn ♦ Habush, Habush & Rottier ♦ Husch Blackwell ♦ Law Offices of Joseph R. Cincotta ♦ Municipal Law & Litigation Group ♦ Perkins Coie ♦ Pines Bach ♦ Quarles & Brady ♦ Reinhart Boerner Van Deuren ♦ Rosen and Holzman ♦ Stafford Rosenbaum ♦ Troutman Pepper ♦ von Briesen & Roper ♦ Wasielewski & Erickson.[3]

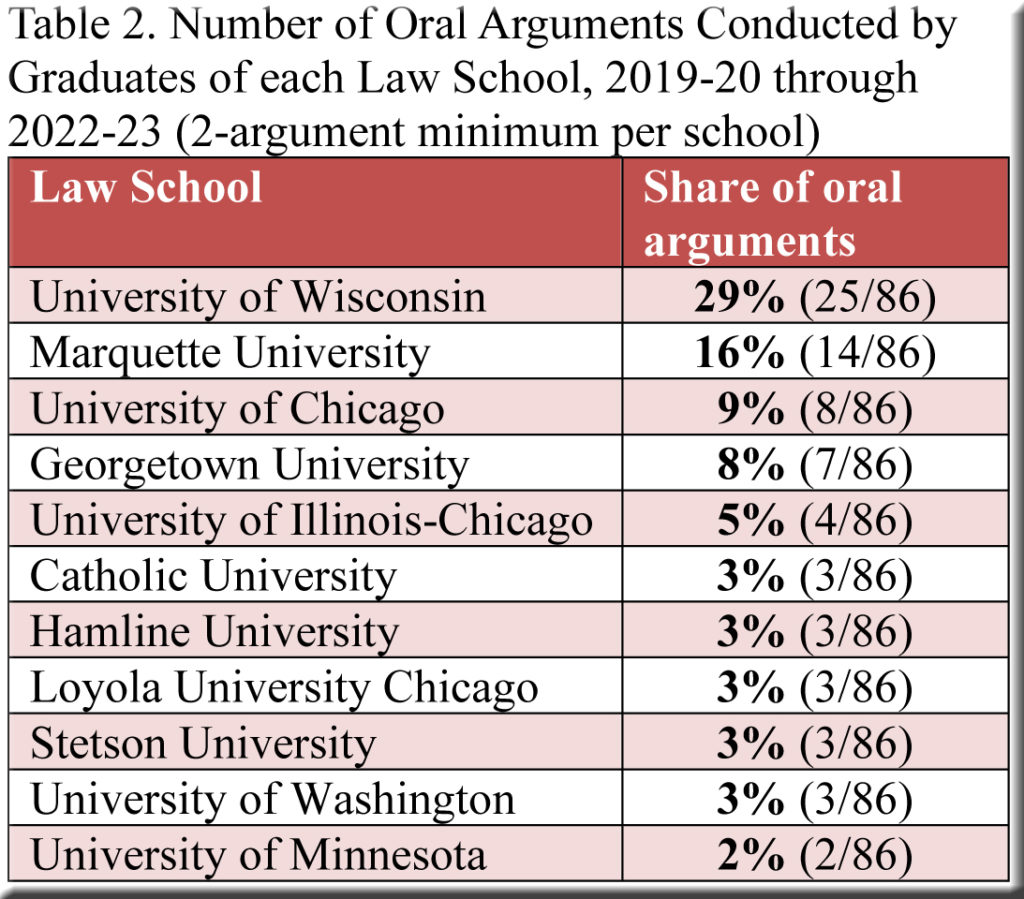

Lawyers from these 18 firms delivered 86 oral arguments in cases decided during the last four terms, and they did so with training from the universities shown in Table 2 (which includes law schools whose graduates presented at least two oral arguments).[4]

Most noteworthy, Marquette’s share (16%) remained exactly where it was during the previous period (2014-15 through 2018-19), while Wisconsin’s portion plunged from 50% to 29%. In a manner of speaking, then, a number of schools in Table 2 enhanced their visibility before the justices at the expense of the University of Wisconsin.

Meanwhile, the law schools’ graduates distributed themselves unevenly among the 18 private firms. That is, various firms appear to have favored, or attracted, attorneys from certain law schools more readily than did other firms, as detailed in Table 3.

Attorney General’s Office

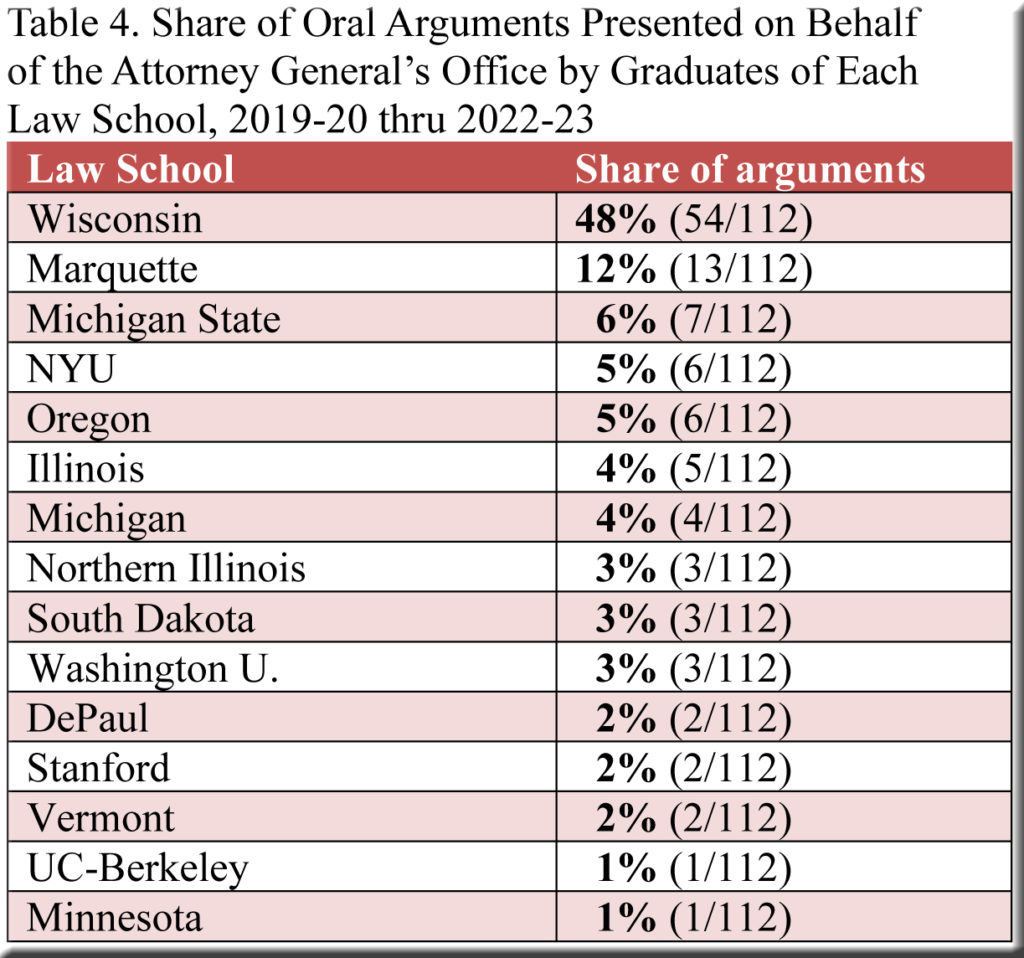

More often than any private firm, or even the top 18 taken together, the Attorney General’s Office sent its lawyers to argue at the supreme court. Just as they did for private firms, the law schools at Wisconsin and Marquette prepared many of these attorneys, but this time it was Marquette rather than Wisconsin whose share fell over the last two periods (by over a third, from 19% to 12%), while Wisconsin’s contribution to the Attorney General’s legions scarcely changed—edging up from 47% to 48% (Table 4).

State Public Defender

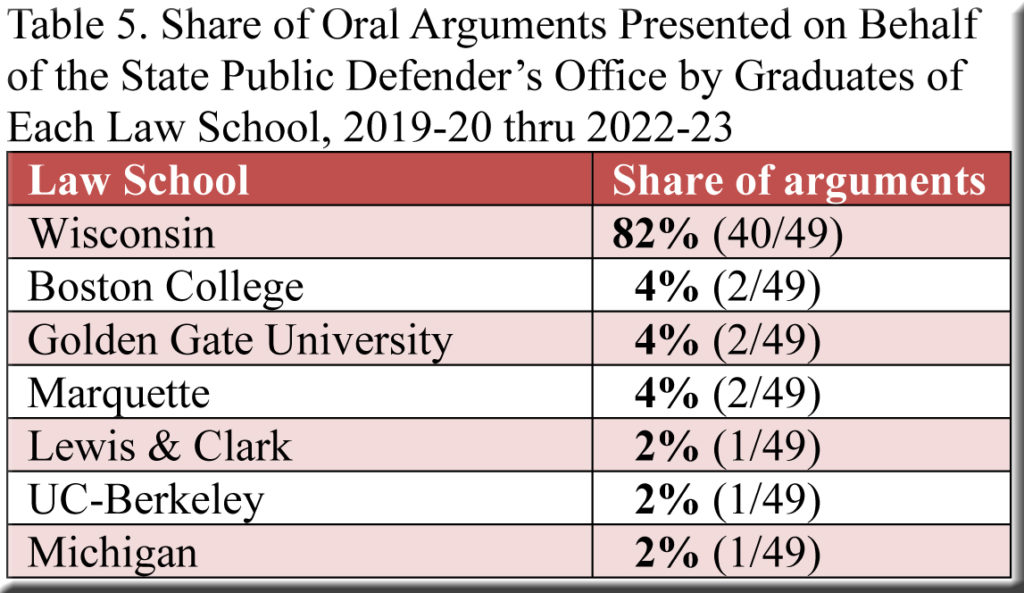

Attorneys from one other state agency, the Office of the Public Defender, also performed regularly before the justices—and nearly all of them obtained their law degrees from the University of Wisconsin. The percentage of Wisconsin graduates has long been massive among the Public Defender’s oral advocates (77% in the previous period), and recently their dominance swelled even more, reaching 82% over the past four terms (Table 5). During the same two periods, Marquette’s share sank from 8% to 4%, now matched by both Boston College and Golden Gate University.

[1] “Law School Representation Rates: Oral Arguments, 2008-9 through 2013-14” and “Law-School March Madness: An Update, 2014-15 through 2018-19”

[2] The figures in this post are derived from cases decided during the four terms under consideration. That is, they do not include oral arguments delivered during this period in cases decided later. Note that the total number of oral arguments delivered (436) far exceeds the total number of cases, as two or more attorneys presented oral arguments in each case. In an extremely small number of cases, multiple lawyers delivered oral arguments for the same party. When this occurred, each attorney’s law school was counted. Numerous lawyers delivered oral arguments in more than one case, and their law schools were credited separately for each argument.

I could not determine the law school of Joseph L. Ford (reportedly from Boca Raton, Florida), who accounted for one of the 436 arguments.

A handful of cases—notably those dismissed as improvidently granted or deadlocked in 3-3 per curiam decisions—do not figure in SCOWstats’s annual statistics and are not included here.

[3] The total for Troutman Pepper includes two oral arguments credited to Troutman Sanders, which merged with Pepper Hamilton to became Troutman Pepper in 2020.

[4] Graduates of the following law schools each presented one oral argument for the 18 private firms: DePaul University, George Washington University, Harvard University, Indiana University, Michigan State University, Northwestern University, University of Michigan, University of Texas, American University, Washington University, and Yale University.

Speak Your Mind