With the last substantive decisions now filed for the 2018-19 term, we can begin a series of posts that examine various aspects of the justices’ labors over the past 12 months.

Number of decisions filed.

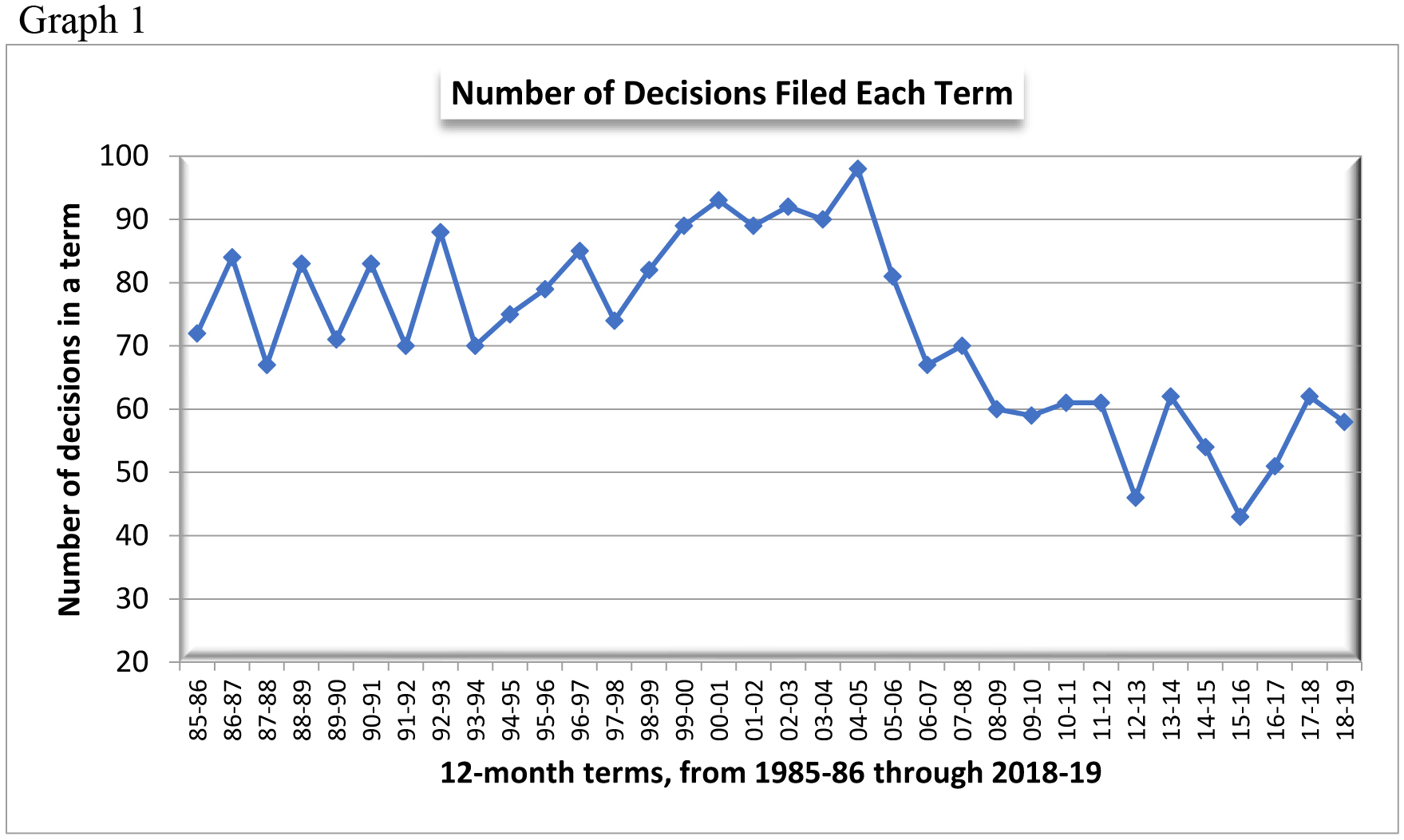

In 2015-16, the court filed just 43 decisions, a modern-era low. Over the next two terms, the total climbed rapidly—reaching 51 decisions in 2016-17 and 62 decisions in 2017-18—but, in 2018-19, the output slipped back to 58 decisions.[1] This is roughly the average for the previous 11 terms, as one can sense from Graph 1.

We can also view 2018-19 in the broader perspective provided by Graph 2. In 1974-75 the court decided 304 cases—an enormous workload that lightened dramatically by the end of the 1970s, as the newly-formed Court of Appeals began to shoulder much of the burden. Even so, the justices continued to file over 100 decisions per terms through 1983-84, and they averaged over 80 per term from 1984-85 through 2005-06, before dropping in the years thereafter to an average approximating the yield of 58 decisions in 2018-19.

Polarization.

The topic of the court’s polarization has figured in numerous posts, and, returning to it today, one is struck both by differences and similarities to themes from prior years.

Regarding similarities, the court’s two most prominent conservatives—Justices Roggensack and Ziegler—remained much more frequent members of the majority in non-unanimous decisions than were the court’s most liberal pair, Justices Abrahamson and Ann Walsh Bradley. Also, as in previous terms, Justices Rebecca Bradley and Kelly voted together nearly all of the time (51 out of 55 cases in 2018-19) and were considerably more likely to side with Justices Roggensack and Ziegler than with Justices Abrahamson and A.W. Bradley.[2]

The conservatives’ strength in 4-3 decisions was just as apparent in 2018-19 as in the preceding term. Although a large number of combinations of justices made up the majorities, conservatives—especially Justices Roggensack and Ziegler—appeared most often, as shown in Tables 1a and 1b.

Yet, in certain respects the figures for 2018-19 are unusual. For instance, as Justice Abrahamson’s health deteriorated, her participation in cases grew more sporadic, and, ultimately, she voted in only 40 of the 58 decisions. Moreover, she authored only one dissent—nothing like her extraordinary average of 16 dissents per year over the preceding five terms, when her output eclipsed that of any other justice. In contrast, all of the other justices wrote more dissents in 2018-19 than she did—an unheard-of result in any of her previous 42 terms on the bench.[3] Such things make it difficult to regard her 2018-19 voting record as characteristic.

Justice Abrahamson also departed from her norm by voting together with Justices Roggensack and Ziegler in non-unanimous cases at a surprisingly high rate in 2018-19. Although she joined each of these conservative justices “only” 38% of the time in such cases—much less regularly than she united with Justices A.W. Bradley and Dallet—this “agreement rate” with the court’s most established conservatives was fully double Justice A.W. Bradley’s rate of agreement with the pair. Furthermore, I checked the preceding ten terms and found Justice Abrahamson a good deal less frequently in agreement with the court’s conservatives throughout the decade. Not only that, she sided with the conservatives less often than did Justice A.W. Bradley during this period—making the outcome in 2018-19 all the more puzzling.[4]

Meanwhile, Justice Gableman was no longer on the court in 2018-19. He had voted with Justices Roggensack and Ziegler 95% of the time in 2017-18, and thus his replacement by Justice Dallet made a difference. She was more likely to vote with Justices Abrahamson and A.W. Bradley than with the Roggensack/Ziegler pair or even the R.G. Bradley/Kelly twosome.

Perhaps these developments help explain one or another of the noteworthy entries in Table 2 for 2018-19, when the number of 5-2 decisions plummeted, while the number of unanimous decisions jumped to a level not seen since 2014-15. I would guess that other factors may have figured as well (possibly the selection of cases or an inclination on the part of the justices to pull in their elbows a bit), and I’d be grateful for suggestions on this score from readers.

In any event, the drop in the percentage of 5-2 decisions from 44% in 2017-18 to 18% in 2018-19 merits closer attention. Not only were these cases much less frequent in 2018-19, but Justices Abrahamson and A.W. Bradley cast the two dissenting votes in only 30% of them—compared to 73% in 2017-18 and 84% in 2016-17. By itself, this would suggest a sharply lower degree of polarization than in recent years.

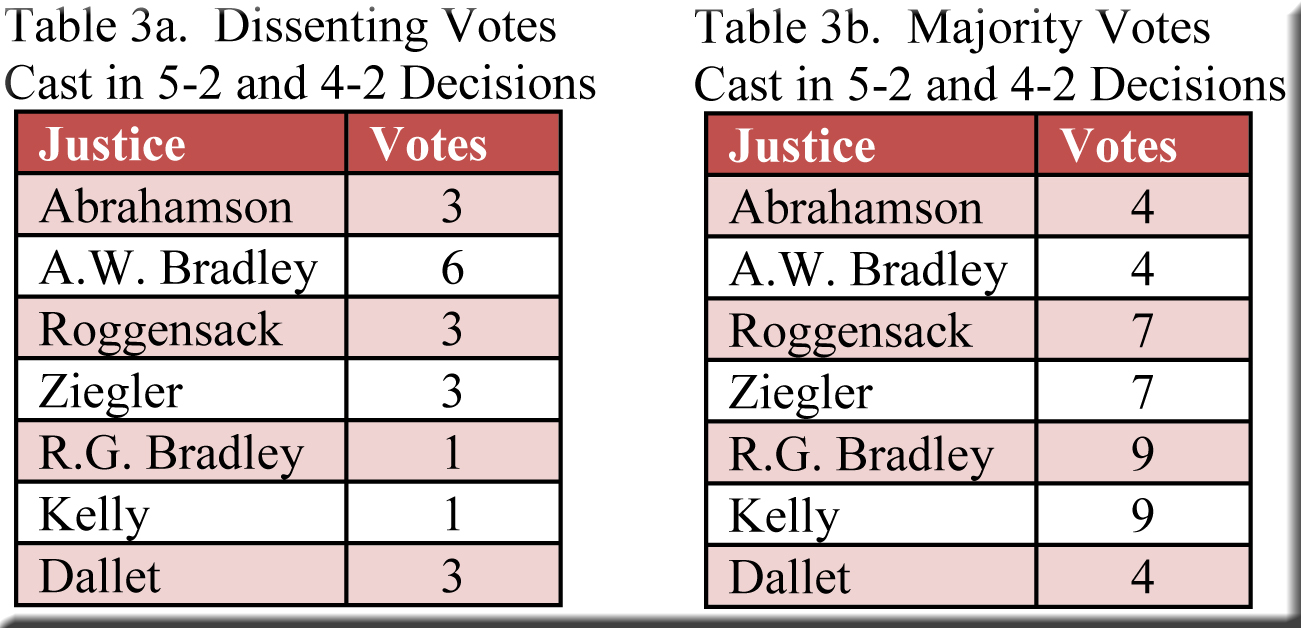

However, the “5-2” decisions were also unusual in that six of the ten were actually 4-2 votes, with Justice Abrahamson absent for three, and Justice Dallet absent for three. In previous years, most “5-2” decisions were just that, with few 4-2 decisions in the mix. Given that Justice A.W. Bradley was one of the two dissenters in five of the six 4-2 decisions, it seems probable that a number of them would have been 4-3 decisions had Justice Abrahamson or Justice Dallet participated. Be that as it may, the following tables indicate that liberal justices (Abrahamson, A.W. Bradley, and Dallet) surfaced much more often in the minority in 5-2 and 4-2 decisions. Indeed, these three justices cast 12 dissenting votes, while all four of their conservative colleagues together cast only 8. As for majority votes in these cases, the liberals accounted for 12 and the conservatives 32.

Conclusion.

As noted above, Justice Abrahamson’s reduced involvement, and the replacement of Justice Gableman by Justice Dallet, contributed to a set of statistics in 2018-19 that diverged in some ways from those of the recent past. Surely, they will also differ from those for 2019-20, when Justice Hagedorn succeeds Justice Abrahamson, for his decisions will reflect an outlook remote from hers. If nothing else, it appears that the court could be at least as conservative as at any point since Justice Abrahamson’s arrival in 1976. Put another way, Justice A.W. Bradley may find herself more isolated than ever, as Justice Dallet is unlikely to occupy common ground with her quite as frequently as Justice Abrahamson did for nearly 25 years. In next summer’s end-of-term post, we can assess this speculation.

[1] The total of 58 decisions omits orders pertaining to various motions, petitions, and disciplinary matters.

Also, when two cases have been consolidated and resolved with a single decision (as in Enbridge Energy Company, Inc. v. Dane County), I normally record this as one case. However, with State v. Raytrell K. Fitzgerald and Raytrell K. Fitzgerald v. Circuit Court for Milwaukee Co., we have a more unusual situation. These two cases were consolidated and handled in a single decision—but, they were argued separately (that is, in two different oral-argument “slots” and consolidated thereafter) and decided by different votes (6-0 and 3-3). Thus, I have counted them as two separate cases.

[2] I will post detailed statistics on the justices’ voting in a few days.

[3] During her very first term on the court (1976-77), she wrote more dissents than all of the other justices combined.

[4] The only exception came in 2015-16, when Justices Abrahamson and A.W. Bradley voted in agreement 100% of the time, thus ensuring that the pair had identical rates of agreement with other justices—more specifically, 12% with Justice Roggensack and 19% with Justice Ziegler. Click here for tables covering rates of agreement in non-unanimous cases for all 11 terms. Incidentally, even had Justice Abrahamson voted “against” Justices Roggensack and Ziegler in every one of the 15 non-per–curiam cases in which she did not participate in 2018-19, her “agreement rate” would still have been 22% with Justice Roggensack and 23% with Justice Ziegler. And, it is unlikely that she would have voted in this fashion in all of these cases, because eight of them were unanimous.

Speak Your Mind