A recent post on “text mining” at the Wisconsin Supreme Court examined majority opinions by running them through Linguistic Inquiry Word Count software (LIWC).[1] Today, we’ll apply LIWC to dissents from the same period (2015-16 through 2017-18) and compare the findings with those obtained for the majority opinions. Justices generally do not invest time in writing dissents without an adamant belief that the court has made a significant mistake, so it may be that their prose in dissent will generate different LIWC “scores” than those that we encountered for majority opinions.

Word Counts

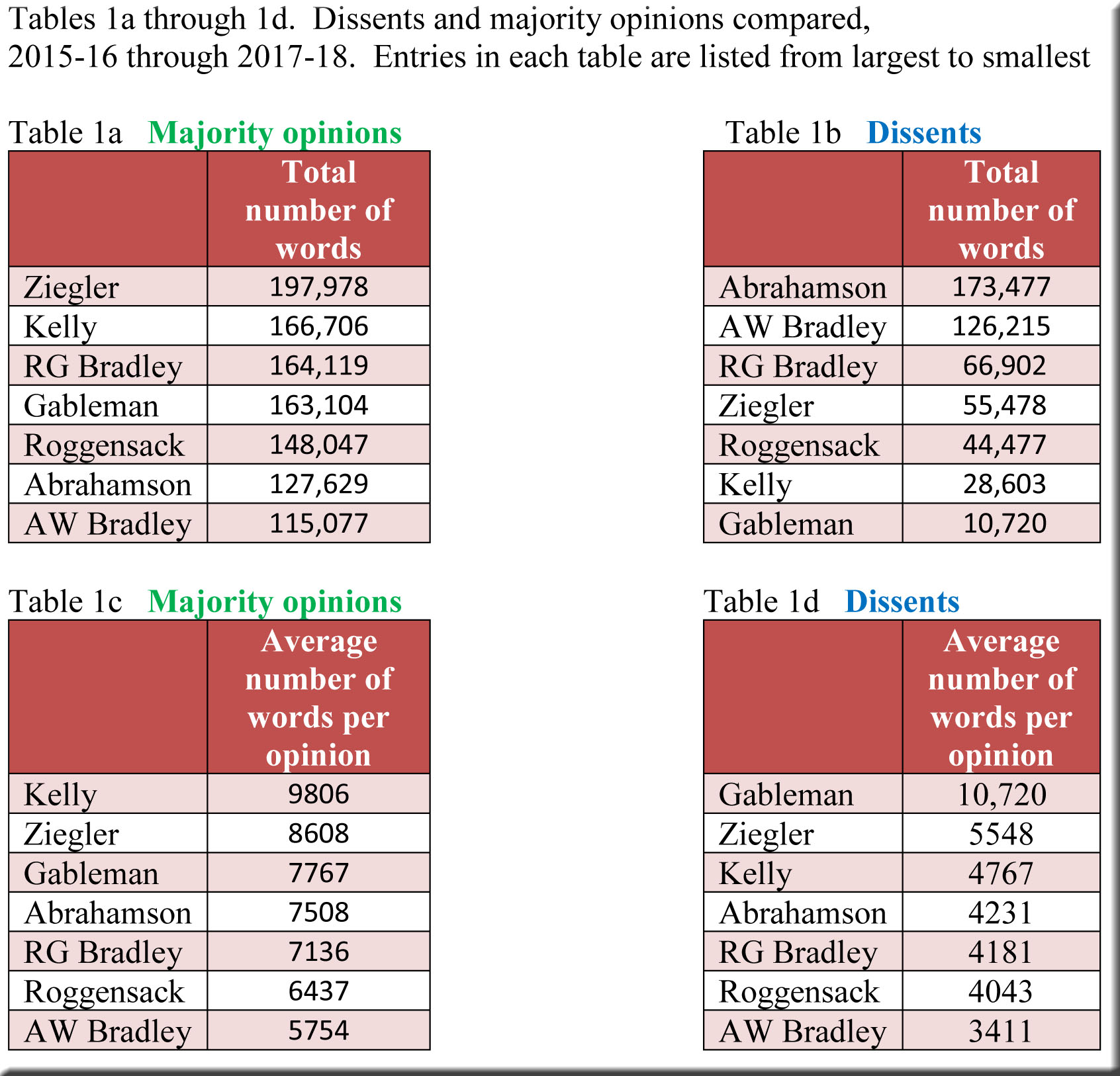

Although the justices are assigned roughly similar numbers of majority opinions, they author dissents at their own discretion. Given that Justices Abrahamson and AW Bradley were most often in the minority, it is not surprising that they alone penned approximately two-thirds of the court’s dissents during this period—which accounts for the most striking contrast between majority opinions and dissents in the first set of tables.[2] Dissents by Justices Abrahamson and AW Bradley are not unusually long (Table 1d), but they are so numerous as to contain close to 50% more words (Table 1b) than all of the dissents composed by the other five justices combined. In fact, Justices Abrahamson and AW Bradley (especially Justice Abrahamson) produced many more words in dissent than in their majority opinions (Tables 1a and 1b).[3]

One thing that changed very little between majority opinions and dissents is the ranking of justices according to the average length of their opinions (Table 1c and 1d). Justices Ziegler, Kelly, and Gableman expended the most toner in both categories, with the other four justices ranked in exactly the same order below them in each table.

Tenor of Opinions

Next, we turn to LIWC’s four “summary variables”—“Analytical Thinking,” “Clout,” “Authentic,” and “Emotional Tone”—derived from proprietary algorithms and described in LIWC’s documentation:

Analytical thinking: “A high number reflects formal, logical, and hierarchical thinking; lower numbers reflect more informal, personal, here-and-now, and narrative thinking.”

Clout: “A high number suggests that the author is speaking from the perspective of high expertise and is confident; low Clout numbers suggest a more tentative, humble, even anxious style.”

Authentic: “Higher numbers are associated with a more honest, personal, and disclosing text; lower numbers suggest a more guarded, distanced form of discourse.”

Emotional tone: “A high number is associated with a more positive, upbeat style; a low number reveals greater anxiety, sadness, or hostility. A number around 50 suggests either a lack of emotionality or different levels of ambivalence.”[4]

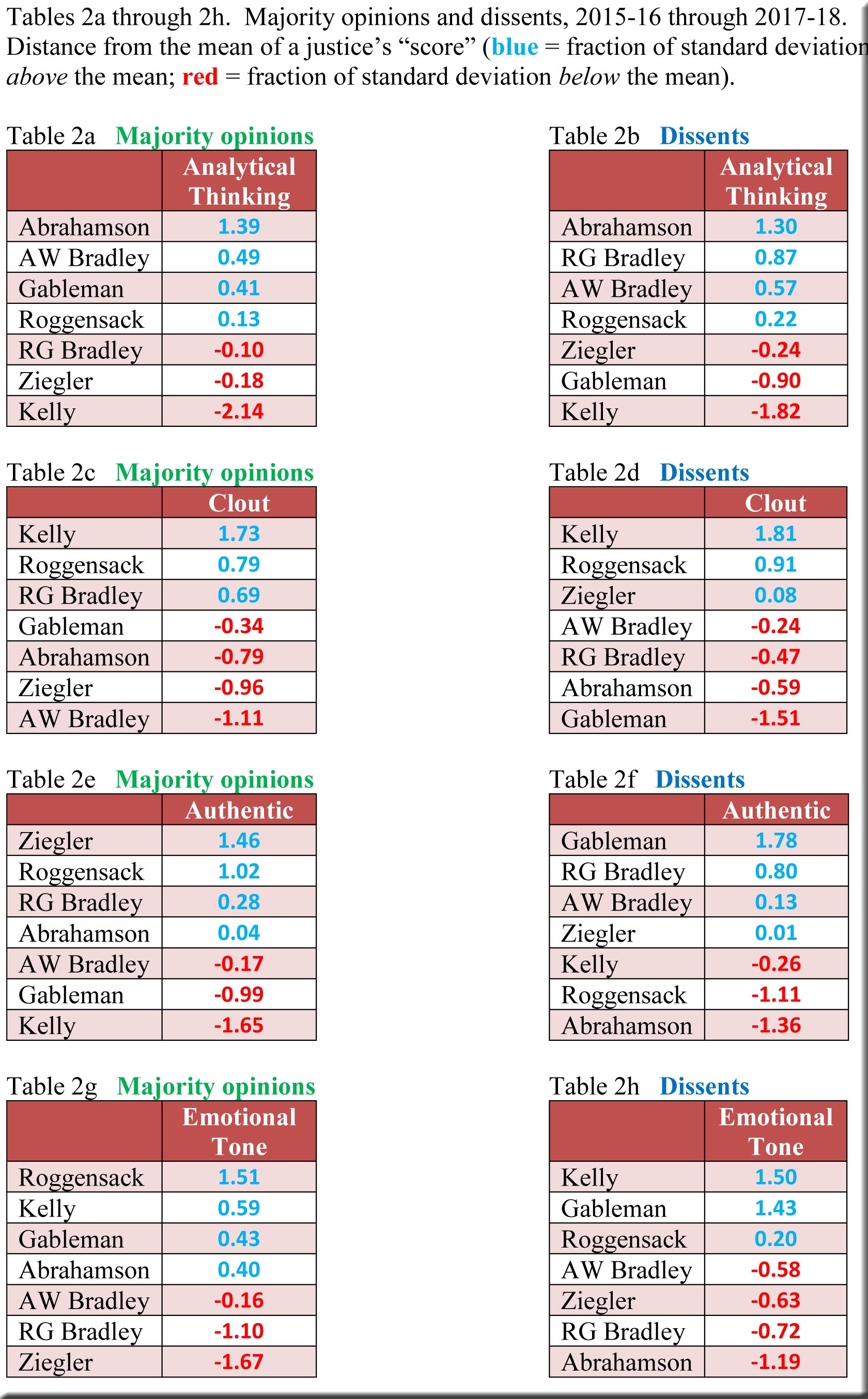

In the “Analytical thinking” and “Clout” categories, most justices “scored” higher with their majority opinions than with their dissents, while dissents generally posted higher “scores” in the “Authentic” and “Emotional tone” columns.[5] As one might expect, given the nature of judicial opinions, “scores” for both majority opinions and dissents were highest for “Analytical thinking,” followed by “Clout.” “Emotional tone” “scores” trailed at some distance, with “Authentic” “scores” a good deal farther back.[6]

To compare each justice’s LIWC “scores” with those of his/her colleagues, we will utilize standard deviations to help provide a rough idea of how far each justice’s “scores” depart from the average (or mean) for the group. As explained in the previous post, a number close to zero in the following tables indicates that a justice is near the group’s average, while a higher number (generally between 1 and 2) places a justice’s “score” well above the average. In similar fashion, negative numbers ranging from -1 to -2 represent a “score” much below the mean.[7] Thus, the figures for Justice AW Bradley (0.13) and Justice Ziegler (0.01) in Table 2f denote “scores” very close to the court’s average, whereas two “scores” for Justice Kelly sit considerably below the mean (-1.82 in Table 2b) or above it (1.81 in Table 2d).

As this illustration suggests (and was also the case regarding majority opinions), Justice Kelly’s dissent results are conspicuous—farther below the mean than any other justice in the “analytical thinking” category and above everyone else in “clout.” His “score” in the “authentic” category resides below the mean (though not as far below it as does his “score” for majority opinions), while he tops the “emotional tone” chart for dissents. In all four categories, his majority-opinion “score” and his dissent “score” are either both above, or both below, the court’s average (Tables 2a through 2h).

In fact, much more often than not—68% of the time—justices who are above (or below) the mean for majority opinions are also above (or below) the mean for dissents. Justice Abrahamson is the only exception, with three of her four majority-opinion “scores” above the mean, and three of her four dissent “scores” below it.

Words of Emotion

Our last topic delivers a surprise regarding words associated with various emotions, which LIWC counts and presents as percentages of an author’s total number of words—a simpler approach than that of the “emotional tone” algorithm in the preceding section. I had guessed that words linked to negative emotions would yield higher LIWC “scores” for dissents than for majority opinions, but this occurred less than half the time.

LIWC’s output includes a general “negative emotion” category and three more-specific negative categories: “anxiety,” “anger,” and “sad.” Surely, dissents by authors who are regularly frustrated or dismayed would “score” higher in these categories than do majority opinions. However, nearly two-thirds of the time—particularly in the “negative emotion” and “anger” columns—the LIWC “scores” for dissents are lower than they are for majority opinions.[8] Meanwhile, in LIWC’s general “positive emotion” category, five justices “scored” higher in their dissents than in their majority opinions. To be sure, there is often very little difference between a justice’s dissent and majority-opinion “scores,” but even this I did not anticipate.[9]

For the most part, the justices’ comparative “scores” (expressed in standard deviations as before) resemble the earlier post’s majority-opinion findings. Once again, Justice RG Bradley seized the headline—as her dissents (like her majority opinions) were judged by LIWC to be the most promising place to search for words associated with positive and negative emotions overall. In all five categories applied to the justices’ dissents (Tables 3b, d, f, h, and j), she ranks #1 or #2.[10]

Conclusion

While explanations come readily to mind for some of these results—why Justices Abrahamson and AW Bradley would produce so many words in dissent, for instance, or why the justices “scored” higher in “Analytical thinking” and “Clout” than in the “Authentic” or “Emotional tone” categories—I struggle to account for other outcomes. The question of why one justice “scored” well above another justice in this or that category would doubtless spark debate, for example, as would attempts to explain why dissents did not surpass majority opinions in “negative emotion.” As always, I am eager to benefit from readers’ thoughts on these and other issues churned out by LIWC.

[1] J.W. Pennebaker et al., The Development and Psychometric Properties of LIWC2015 (Austin, TX: University of Texas at Austin, 2015). See the initial post for some articles whose authors have utilized LIWC and who discuss its capabilities and limitations.

[2] I am not including a handful of co-authored dissents (by Justices Abrahamson and AW Bradley and by Justices Kelly and RG Bradley). Dissents by Justice Prosser are also excluded, because the tables cover only his final term. Justice Kelly is included, though his data come only from 2016-17 and 2017-18.

[3] While the volume of dissents from Justices Abrahamson and AW Bradley provided LIWC with an abundance of text, Justice Gableman wrote only one dissent during the entire period. As the figures for Justice Gableman in all of this post’s tables have been derived from this single (though lengthy) dissent, they should be interpreted cautiously.

[4] James W. Pennebaker et al., Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count: LIWC2015 (Austin, TX: Pennebaker Conglomerates, 2015). The pages are unnumbered; see the second page from the end.

[5] This pattern did not fit Justice Abrahamson in three of the four categories, but for the other six justices it held true in every instance, or all but once (for Justices Roggensack and RG Bradley).

[6] Click here for a table that provides the justices’ raw LIWC “scores” for dissents and majority opinions separately.

[7] It is possible to have numbers higher than 2 and lower than -2, which would indicate an even larger gap—greater than two standard deviations—between a “score” and the mean.

[8] Multiplying the four “negative” categories by seven justices, we get a total of 28 LIWC “scores”—61% of which are lower for dissents than for majority opinions. In the general “negative emotion” and “anger” columns, 86% of the “scores” are lower for dissents.

[9] Click here for a table that contains the justices’ raw LIWC “scores” for dissents and majority opinions.

[10] We noticed in the preceding section that a justice’s majority-opinion “scores” and dissent “scores” in individual categories tend to be either both above, or both below, the mean. This holds true even more frequently for words of emotion—77% of the time in the ten tables that follow—and most dramatically of all for Justice Roggensack (every “score” below the mean) and Justice RG Bradley (every “score” above it). All of Justice Ziegler’s pairs of “scores” also match: below the mean for “positive emotion” and above the mean for the rest.

Speak Your Mind