Now that the court’s final three substantive decisions have been filed, the time has come for the first in a series of posts on the justices’ activities in 2017-18, comparing them to our findings from previous years.

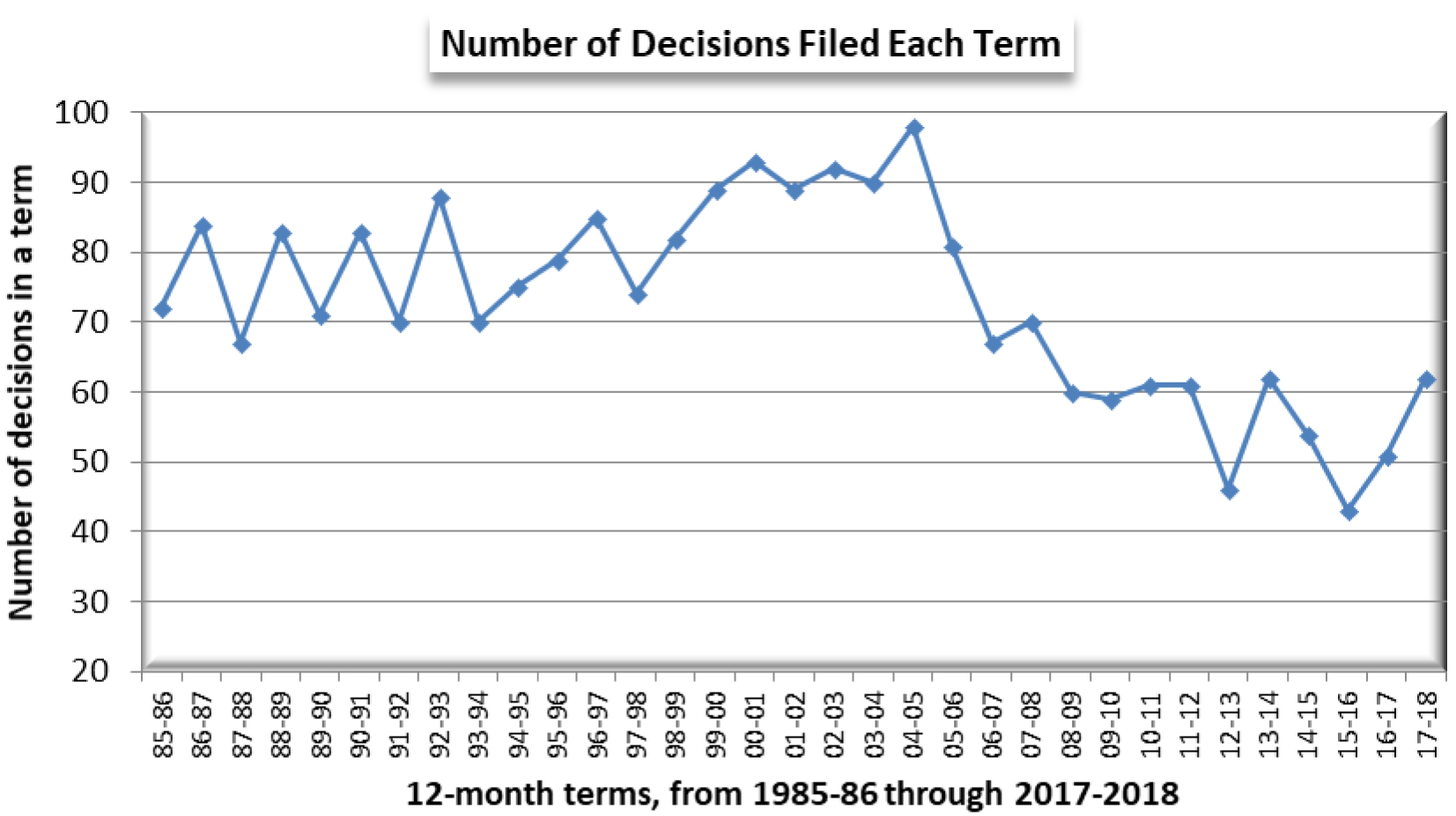

Number of decisions filed.

In 2017-18 the court filed 62 decisions, the second consecutive term to witness a significant increase.[1] The number had declined sharply from 2013-14 to 2015-16 (when it reached a modern-era low of 43 decisions), and it has rebounded just as briskly over the last two terms. The current yield of 62 decisions is close to the totals for the period from 2008-09 through 2013-14 (except for a drop to 46 decisions in 2012-13), though it is well below the number of cases handled before 2008-09, as shown in the following graph. It will be interesting to see if, in the next few terms, the number of decisions (1) fluctuates as conspicuously as it has in recent years, (2) settles in the low 60s, or (3) continues to rise toward the heftier outputs of earlier years.

Incidentally, the graph changes markedly if we extend it back to the point where the court of appeals had just been established, and the supreme court was still accepting all (or nearly all) of its cases directly from circuit and county courts. In 1977-78, the first term covered in the graph below, the justices decided 247 cases, none of which arrived via the court of appeals. The next term, only four of the supreme court’s 245 cases were reviews of decisions by the court of appeals. Thereafter, the court of appeals rapidly became the primary conduit of cases reaching the supreme court—figuring one way or another in 128 of the 134 cases resolved by the justices in 1980-81.[2]

Polarization.

SCOWstats has noted for some time that voting on the Wisconsin Supreme Court has become more polarized in recent years than it was in preceding decades—and the figures for 2017-18 do not challenge this conclusion. When compared to the voting alignments in 2016-17, for instance, the data for 2017-18 may perhaps imply slightly greater polarization in 4-3 votes and slightly less in 5-2 votes, but, in any event, the overall impression of polarization endures.

Tables 1a and 1b give a sense of this, as they indicate that the court’s three most established conservative justices have voted in the majority in nearly all of the ten cases decided by 4-3 margins (Justice Roggensack 8/10, Justice Ziegler 9/10, and Justice Gableman 9/10), while the court’s two liberals (Justice Abrahamson 2/10 and Justice A.W. Bradley 4/10) appeared much less often in the majority. A check of 4-3 cases from the 2016-17 term suggests that the conservatives became a bit more dominant in 2017-18 and the liberals a bit more marginal.[3]

However, as in past terms, more vivid evidence of polarization surfaces in cases decided by 5-2 votes.[4] Not only has a larger share of cases fallen into this category in recent years (Table 2), the court’s two liberals have cast the dissenting votes in most of them—specifically, in 73% of decisions (19 of the 26 cases) with 5-2 votes in 2017-18. This does not quite match the figure for 2016-17 (84%), but it is still dramatic—and far above the percentage of 5-2 votes in which Justices Abrahamson and Bradley were the two dissenters in the years before Justice Gableman joined the court. From 2004-05 through 2007-08, for example, the pair accounted for the dissenting votes in only 31% of 5-2 cases.[5]

Fractured decisions.

A fractured decision occurs when a majority of the court endorses a decision’s mandate, but fewer than four justices agree on the reasoning for it. The rationale garnering three (or potentially only two) votes is called the “lead opinion,” but it has no precedential value. Such an outcome signals that the court has failed to resolve an important issue, leaving the lower courts, lawyers, litigants, and (in criminal cases) law enforcement in doubt about the point of law in question. Consequently, future litigants may have to argue the issue again, and the resulting waste of taxpayer funds and litigants’ resources helps explain the frustration generated by fractured decisions.

These concerns grew more audible in 2015-16, when 14% of the justices’ rulings were fractured—well above the percentage for the previous term and also the average of 2.3% for the period 1996-97 through 2014-15. When the figure crept even higher in 2016-17, to 16%, anxiety arose as to whether such levels had become the new normal. Fortunately, the opinions authored in 2017-18 suggest otherwise, as the portion of fractured decisions dropped to 6% (Table 3).[6]

Conclusion.

Which of the three topics in this post presents the most significant change in 2017-18 compared to the previous term? Clearly not the issue of polarization, which has been acute for some time and remains so today. One might opt for the increase in the number of decisions filed—a jump from 51 to 62—but my money would be on the shrinking percentage of fractured decisions. Not only was the decline from 16% to 6% precipitous, the unhelpfulness of fractured decisions makes their reduction all the more noteworthy.

Over the days and weeks to come, SCOWstats will offer more statistics and impressions of the court’s 2017-18 term.

[1] The total of 62 decisions includes three 3-3 per curiam decisions. It does not include (1) orders pertaining to various motions, petitions, and disciplinary matters, and (2) a case dismissed because review had been improvidently granted (Mark Halbman v. Mitchell J. Barrock).

[2] Of the 128 cases, 110 were reviews of decisions by the court of appeals; eight arrived on bypass from the court of appeals, and 10 were certified by the court of appeals.

[3] Here are the figures for the same justices in 4-3 cases decided in 2016-17: Abrahamson (three majority votes in six 4-3 cases), A.W. Bradley (3 out of 6), Roggensack (3 out of 6), Ziegler (5 out of 6), and Gableman (5 out of 6).

[4] This category includes a few cases decided by 4-2 votes.

[5] For more data on the isolation of Justices Abrahamson and A.W. Bradley during the past decade, see “The Butler-Gableman Divide: Wisconsin Supreme Court Elections Matter.”

[6] The total of four fractured decisions in 2017-18 includes Tetra Tech EC, Inc. v. Wisconsin Department of Revenue—a portion of which was described as a lead opinion and another portion as a majority opinion. One could argue that 3-3 per curiam decisions should also be classified as fractured, but I have not done so in this table.

Speak Your Mind