Wisconsin’s Public Records Law, written to secure for citizens and the media access to records pertaining to the functioning of state and local government, has commanded frequent headlines of late—especially in the wake of periodic efforts by legislators and the Walker administration to reduce public access to such materials.[1] No doubt this attention, along with public-records requests made of Supreme Court justices themselves, helps account for the suggestion that I received to explore the voting patterns of the court’s members in cases involving attempts to obtain information by invoking the Public Records Law.

To assemble a set of cases for the period 1995-96 through 2014-15, I began by searching for all decisions containing the term “19.3”—thereby turning up references to the Public Records Law: Wis. Stat. §§ 19.31-19.39. I then weeded out irrelevant decisions, such as those that mentioned the law in a peripheral manner, without discussing how or whether the statute applied to the issues before the court. Omitted, too, were a very small number of other cases: (1) a per curiam decision; (2) cases that included public-records issues but were decided on non-public-records grounds; and (3) cases that yielded decisions neither entirely in favor nor entirely opposed to the arguments of the parties requesting records. I also excluded Journal Times v. City of Racine (2013AP1715) because the issue did not pertain to furnishing documents but rather the payment of attorney fees in the unusual circumstances of the case.

This yielded a set of 14 cases in which 71% of the decisions (10 of 14) favored access to records. Before scrutinizing the decisions, one might hypothesize that liberal justices would be the most inclined to favor open access to records, while conservatives would be least sympathetic to such requests. Justice Abrahamson did nothing to discourage such speculation in the introduction to her majority opinion in Karen Schill v. Wisconsin Rapids School District. Observing that the week of March 14, 2010, was “Sunshine Week,” and quoting with approval an editorial in the Wisconsin State Journal, she emphasized that Wisconsin’s open government laws “‘are first and foremost a powerful tool for everyday people to keep track of what their government is up to. … The right of the people to monitor the people’s business is one of the core principles of democracy.’”

If a liberal court were more disposed to favor public-records requests, we would expect to see a lower percentage of such decisions over the past 7 terms, when the court’s rulings turned more conservative. However, such has not been the case, for during this period 75% of the court’s decisions (3 of 4) favored access. To be sure, the small sample size demands caution in forming conclusions, so let’s consider a larger subset of 8 cases and compare the votes of Justices Abrahamson and Roggensack—the most liberal and one of the most conservative justices who have both been on the court long enough to have cast votes in all 8 decisions. If the simple liberal-conservative predictor were useful, one would expect Justice Abrahamson to approve access more frequently than did Justice Roggensack, but, as it turned out, each justice voted in favor 5 out of 8 times.

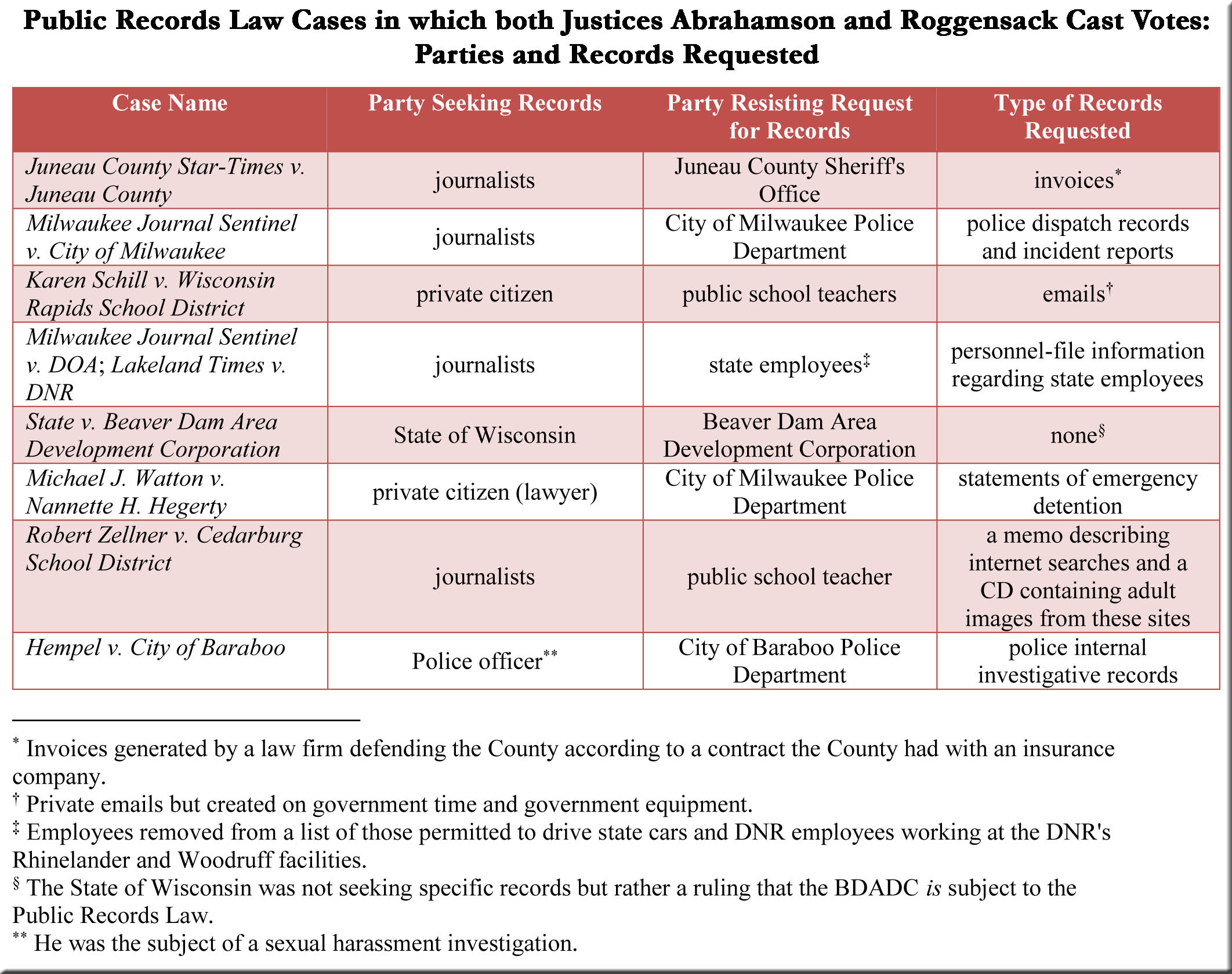

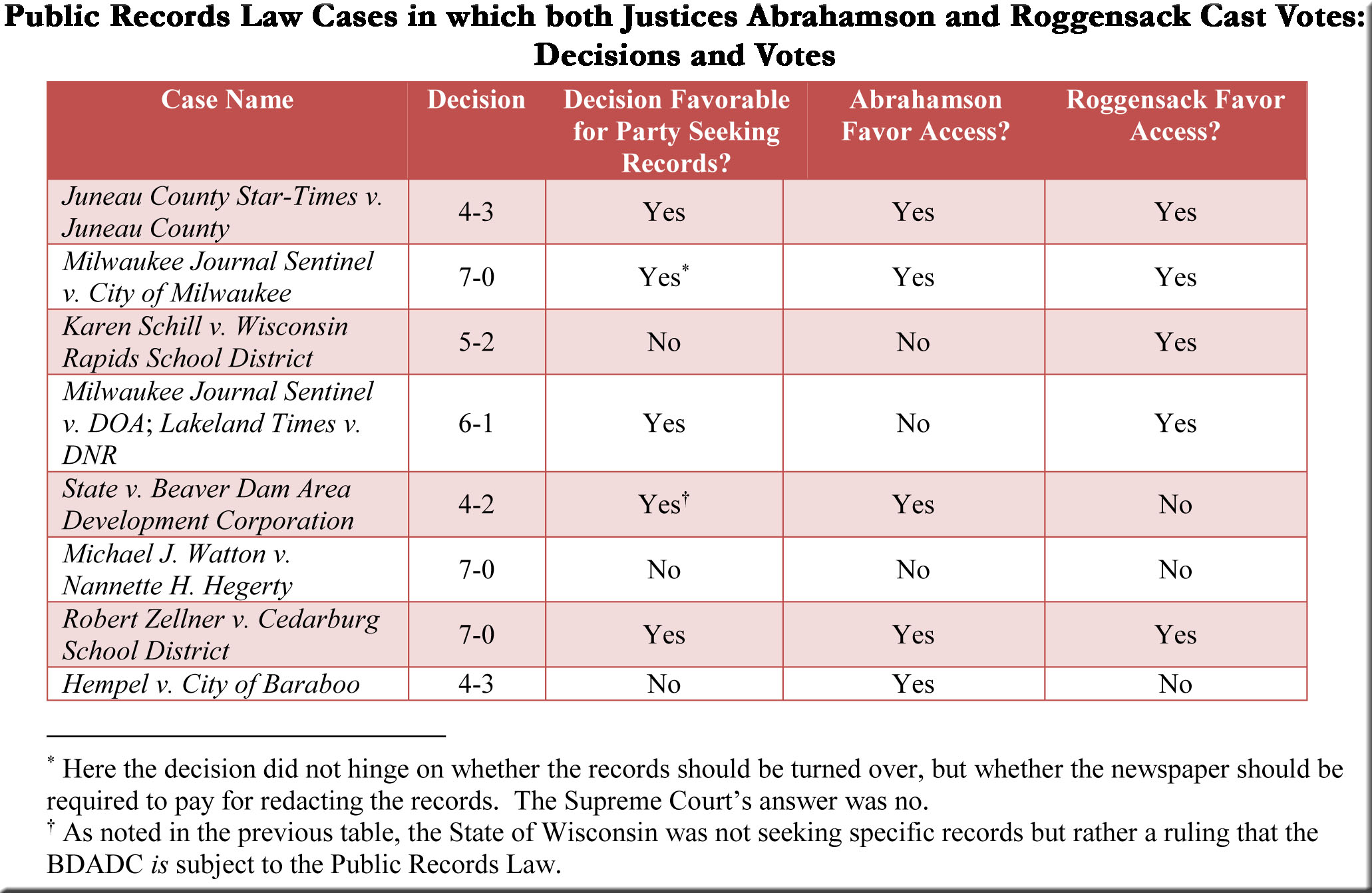

They did not vote to grant access in all of the same cases, though, disagreeing just as frequently as they agreed, as evident in the following tables. (Click on the tables to enlarge them.)

Of course, the sample size remains small, and explanations for the different votes cast by the two justices must remain circumspect. But it seems plausible—perhaps even self-evident, as it would for other categories of cases too—that the identity of the parties and the specifics of the dispute go much of the way toward predicting and explaining the decisions of individual justices. Thus one might scrutinize the details of each case to see if there are subcategories of parties or issues that result in justices voting in ways that do not support the “liberal favors access; conservative opposes access” assumption and could help explain the information in the tables. Hypotheses formed in this manner could then be tested against future public-records decisions issued by the court.

To suggest an example, consider public-records cases in which public-employee unions presented arguments asking the court to forbid the release of information about their members—information sought by other parties through Public Records Law requests.[2] Here the “rule” of “liberal favors access; conservative opposes access” does not fit well at all, and, indeed, the opposite is a more accurate guide. As noted, the unions opposed access to records about their members, and Justice Abrahamson sided with them in 2 of the 3 cases—while Justice Roggensack favored access to the records all 3 times. Thus, in dissenting from Justice Abrahamson’s majority opinion in Schill that blocked the release of private emails sent by public-school teachers while on the job, Justice Roggensack lamented that “the court contravenes Wisconsin’s long history of transparency in and public access to actions of government employees. It is contrary to the letter and the spirit of the Public Records Law and is a disservice to the public’s interest in government oversight.” Were the author of these words unknown, one might readily attribute them to Justice Abrahamson, arguably the court’s most vocal champion of open government.

Viewing this another way, if we remove these three “union” decisions from consideration, Justice Abrahamson favored access to records in 80% of the remaining public-records cases, while Justice Roggensack’s percentage would fall to 40%. No doubt there are other subcategories of cases that, if identified, would help explain the justices’ public-records votes, and I would be grateful for suggestions that readers can offer.

That said, if current politics gives rise before long to public-records cases that reach the court, one might expect liberal and conservative labels to coincide more precisely with the votes of individual justices. Put bluntly, it would be headline news if conservative and liberal justices did not vote predictably in cases challenging the efforts of Republican legislators and the Walker administration to curtail the scope of the Public Records Law.

Meanwhile, though, there may be another factor that affects, if only subconsciously, the justices’ public-records decisions in ways not always in line with customary ideological stances. For instance, it seems probable that no other category of case requires the justices to rule on demands that are more likely to be applied in turn to the justices themselves. They may not worry that their own homes and cars will be searched with greater abandon by police officers following the court’s Fourth-Amendment rulings, in other words, but it is difficult to imagine that the justices share a similar serenity about the personal consequences of their public-records decisions. If such speculation appeared farfetched years ago, it is more credible in the current political climate and in light of recent articles reporting that three of the court’s members—Justices Abrahamson, Rebecca Bradley, and Gableman—are indeed the subjects of public-records requests made by political opponents.[3] It would be a rare set of human beings who could remain completely unaffected by an awareness that their rulings in similar cases might provide them with a sturdier defense, or leave them more vulnerable, when facing public-records requests from their own ideological adversaries.

[1] See for example: “Lawmakers slash public records access in budget bill”; “Quiet change in public records policy could shield messages”; “State board may have overstepped authority on open records”; “State officials backtrack on open records changes”; and “Scott Walker insists his office follows open records law” (all in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel) and “Plan to curtail public records laws sparks uproar” (from the Post-Crescent of Appleton, WI, reprinted in USA Today).

[2] Karen Schill v. Wisconsin Rapids School District; Milwaukee Journal Sentinel v. DOA (consolidated with Lakeland Times v. DNR); and Robert Zellner v. Cedarburg School District.

[3] “Three justices slow to provide documents under open records law”; “Justice Rebecca Bradley’s meetings calendars empty for 2 1/2 years” (Milwaukee Journal Sentinel).

Speak Your Mind